What Singapore is saying by expelling China hand Huang Jing

To understand the Lion City’s motives, look to the ton of bricks that fell on an outspoken academic – and the experience of an American diplomat nearly 30 years ago

Older Singaporeans travelling beyond Asia are all too familiar with encountering ignorance about their country’s geography. “You’re from Singapore? Is that part of China?”

Being the only Chinese-majority state outside Greater China and being no larger than a city, some confusion about Singapore’s status is understandable. After 52 years, Singapore still finds itself needing to educate the world that it is a sovereign republic.

It marked the first time in more than two decades that Singapore had publicly booted out an alleged functionary of a foreign power for interference in its domestic affairs.

Singapore did not name the country Huang Jing was supposedly working for, but most people assume it is China, the country of his birth. The affair has sparked intense discussion and speculation. Since such expulsions are invariably symbolic, the question is what Singapore is trying to communicate.

The move has to be read in the context of a rising China. Like most other countries, Singapore is having to adjust to this megatrend. Ironically, Singapore played a prominent role in helping the West understand China in its early opening-up years. Singapore feared, and continues to fear, that if the relationship is mismanaged, China’s Asian neighbours will pay the price.

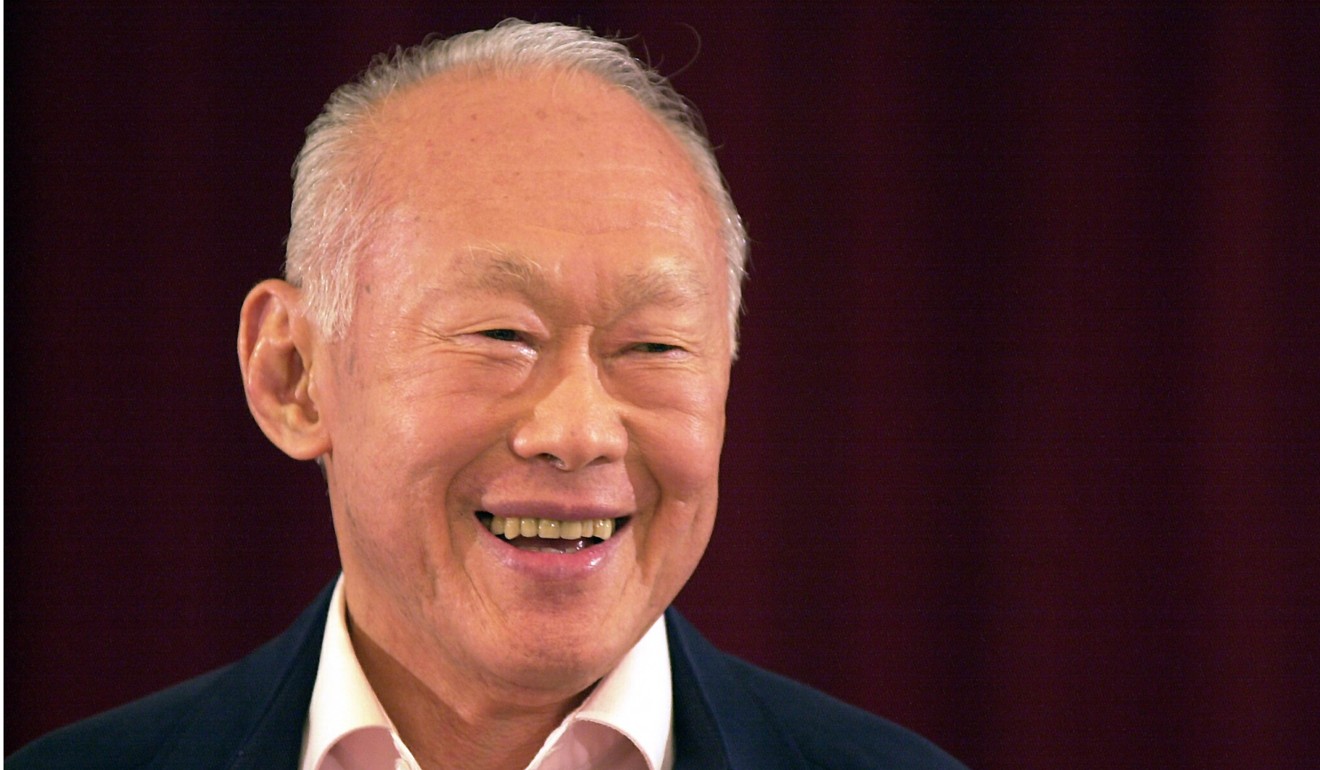

Singapore’s late elder statesman Lee Kuan Yew was determined to persuade the United States not to alienate this emerging Asian power but to encourage it to play a responsible role in the international community. Lee was such an effective China whisperer he was sometimes misunderstood in the West as a Beijing stooge.

More recently, Singapore has been dealing with the opposite perception problem. China, already arrived as a major global player, has been hinting that Singapore is too pro-American and not giving enough face to its Asian neighbour.

Analysts point to various Singapore actions that displeased Beijing. Huang himself has enumerated what he saw as strategic errors. On a Chinese current affairs programme in April now making the rounds online, he said Singapore should not have spoken up about the arbitration of the South China Sea dispute between the Philippines and China. Huang also suggested Singapore had gone overboard in selling the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which China was not a part of. Lastly, Singapore had put too much faith in Barack Obama’s Asia rebalancing or pivot strategy, assuming that Hillary Clinton would be elected and build on it.

Was Lee Kuan Yew rushed into signing his last will?

Although putting up a brave face, there have been clear signs that the Singapore government is extremely sensitive about claims that it may have made mistakes in managing relations with China. In December last year, two academics from the Rajaratnam School of International Studies, which has links to Singapore’s security and foreign policy elite, wrote an op-ed criticising Singaporean commentators by name (as well as the South China Morning Post) for stating the obvious – that the Terrex affair was a sign of China’s irritation. The academics claimed such speculation was unfounded and “misguided assertions” could just fuel domestic anger and escalate the situation.

Singapore will not ‘roll over’ for China

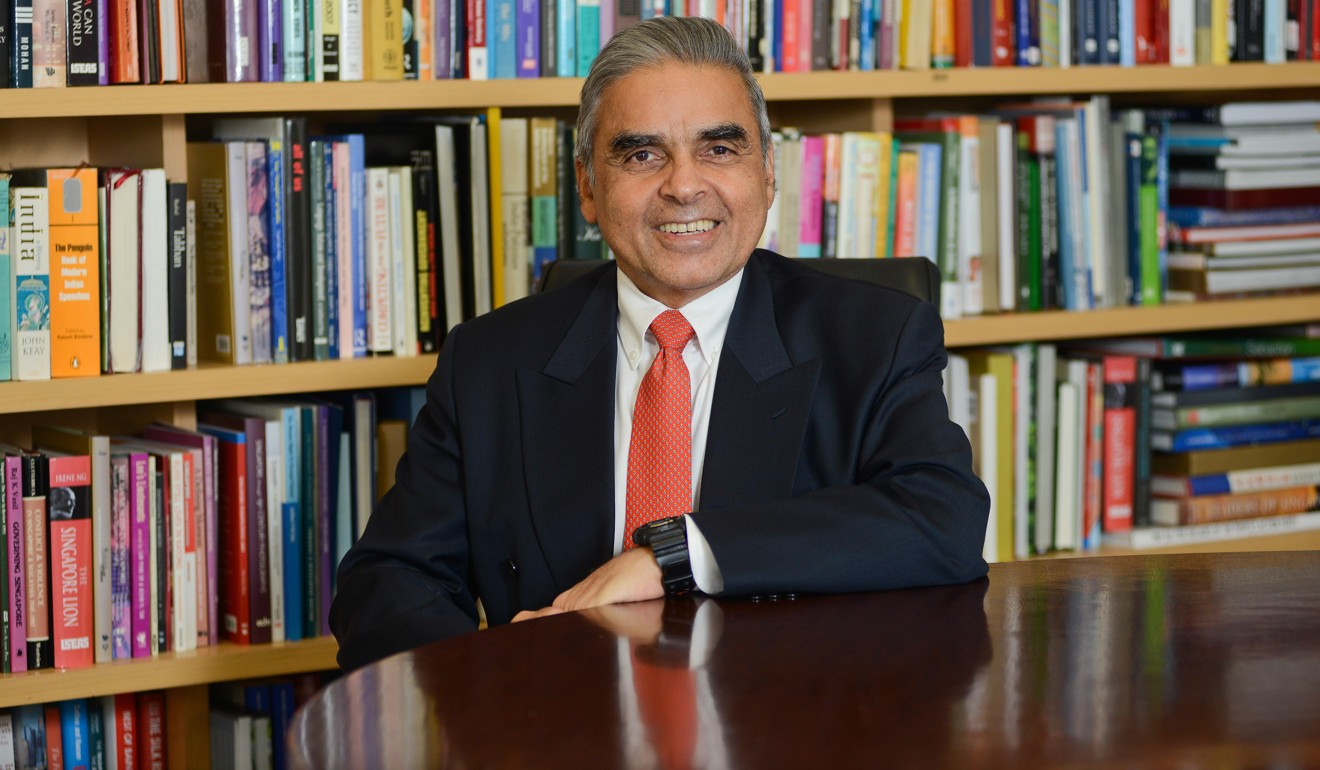

A much stronger reaction greeted career diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School, when he wrote an article urging Singapore to “exercise discretion” and “be very restrained in commenting on matters involving great powers”. He mentioned in particular the China-Philippines maritime dispute, saying that it “would have been wiser to be more circumspect”.

A ton of bricks fell on Mahbubani. His highly influential former colleague Bilahari Kausikan called his argument “muddled, mendacious and indeed dangerous”. The powerful Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam said it was “questionable, intellectually” and ran contrary to the thinking of the late Lee Kuan Yew.

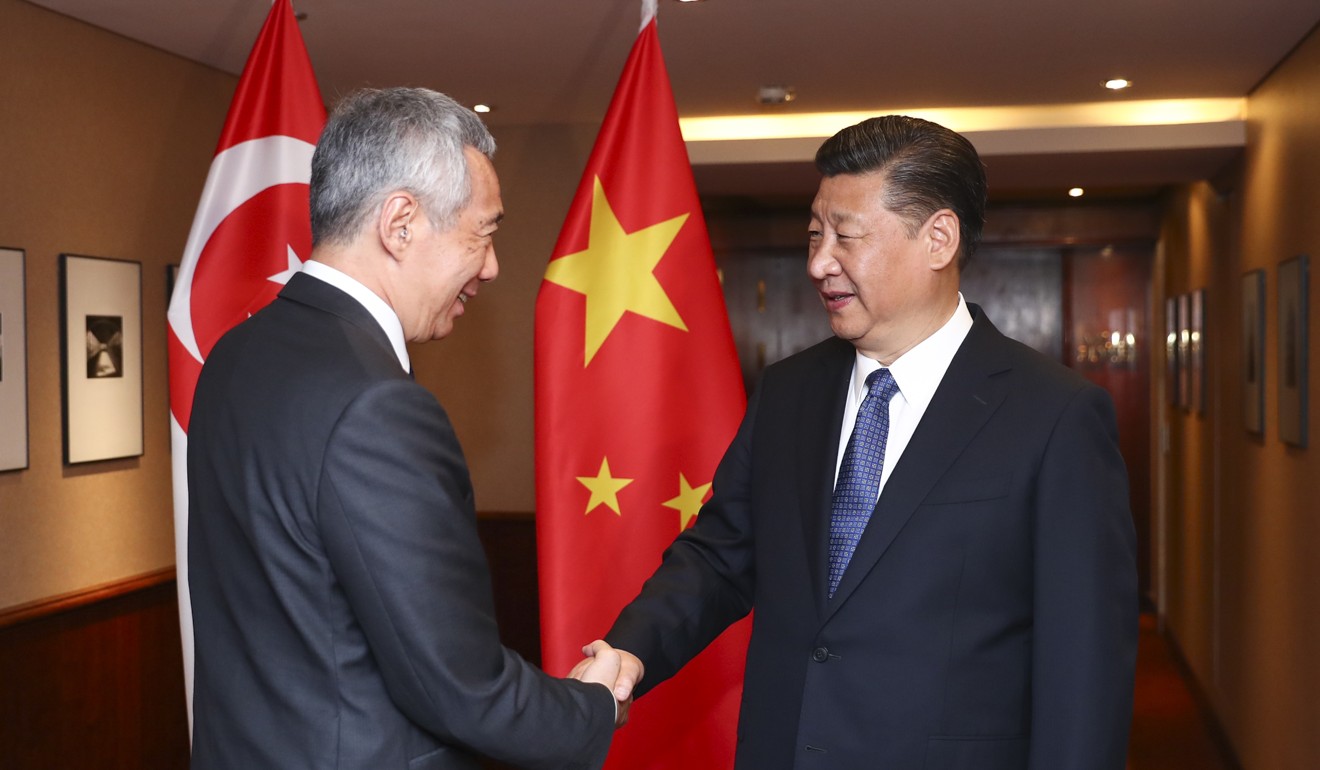

Meanwhile, Singapore-China relations seem to be warming up. Xi and Lee met ahead of the G20 Summit in Hamburg, Germany last month, where they “affirmed the substantive bilateral relationship”, according to the prime minister’s office. State-run Xinhua quoted Xi as saying China was “ready to work with the Southeast Asian country to enhance the bilateral partnership step by step”.

At the recently concluded Asean meeting in Manila, Singapore’s foreign minister Vivian Balakrishnan met with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi ( 王毅 ). The statements from both sides were positive. Balakrishnan told the media later that “the challenges we’ve had in the last one or two years are actually part of a maturation process in our relationship”.

To interpret the Huang Jing affair, we can also turn to history. The last similar case was in 1988. The American embassy’s first secretary E. Mason Hendrickson was expelled for allegedly urging a group of lawyers to contest elections. The US protested that he was just doing his job of keeping in touch with the opposition, and expelled a Singaporean diplomat in retaliation.

2016: Year of the Man? These women were ahead of their Time

This fracas coincided with a period when Lee Kuan Yew was preparing to hand over the premiership to his successor, Goh Chok Tong. With the cold war ending, it was also an era when the US was particularly active in exporting democracy and human rights.

Singapore was – and remains – a great believer in a strong US presence in the region. From that low point, relations did return to an even keel with a deal signed in 1990 that paved the way eventually for Singapore to offer logistical support to the US military, including the Pacific fleet. But back in 1988, Singapore felt it needed to send a message to the superpower that, like with any close friendship, there must be clear boundaries.

Singapore’s shock expulsion of Huang Jing can be read in the same light.

A signal has been sent: the Lion City is tiny and depends on the friendly cooperation of China; but contrary to ignorant opinion, Singapore is its own country. ■

Zuraidah Ibrahim is the editor of This Week in Asia