All work and no play: why more Hong Kong children are having mental health problems

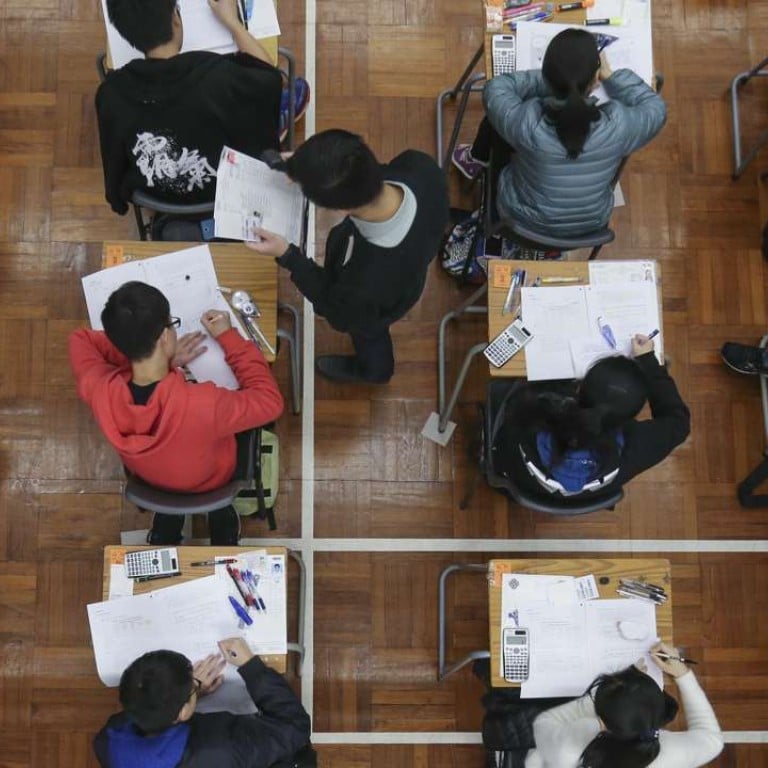

An examinations-based education system, family pressure and little outdoor time are partly to blame

Children in Hong Kong are becoming increasingly stressed out, overworked and unhappy, and the situation is taking its toll on overburdened psychiatric services.

The overall number of mental health patients increased by 2 to 4 per cent every year, from about 187,000 in 2011-12 to more than 226,000 in 2015-16, according to the Hospital Authority.

Experts say the findings are sadly unsurprising, given the much publicised pressures facing the city’s young people – namely an intense examinations-based education system and high family expectations.

One of the government’s recommendations in its recent mental health service review was that schools should adopt a more interventionist approach in cases where they consider pupils to be suffering from poor mental health.

But it failed to account for the shortage of doctors in Hong Kong available to treat mental health problems; there are about 330 psychiatrists employed in the city’s public hospitals – 400 fewer than the number recommended by the World Health Organisation, taking into account the city’s population. Families more than ever are forced to address the problem themselves.

Watch: Student questions Secretary for Education in Legco

Dr Ivan Mak Wing-chit, a private psychiatrist, urged parents to talk more to their children, saying it was more important for their early development than academic results.

He said he was treating increasing numbers of children for mental health conditions including anxiety and depression, adding that his youngest client was just 10 years old, with the average age of his child patients decreasing.

“I would describe the state of mental health among our youth as worrying,” he said. “We need more urgent measures, but it cannot just be one sector or one government department; all stakeholders must work together.”

Mak said children who lacked strong social bonds with their family in the early years may experience more serious mental health problems in adulthood.

“In serious cases, they may always have the sense of emptiness and loneliness, no matter how many friends they have,” he said. “This craving for love never ends.”

Early drilling

The crisis suggests Hong Kong’s young minds are struggling to cope in the city’s emotional pressure cooker.

The Chinese “tiger mum” archetype, where parents push children to exceed academically without regard for their well-being, appears to hold water in Hong Kong, and may be a contributing factor to the mental health decline of its young.

Almost half of those polled also said they had enrolled their kindergarten or primary school child in at least two after-school tutorial classes and music classes.

Despite this, 77 per cent of respondents agreed it was appropriate to nurture children by providing them with space and freedom.

Assistant Professor Eva Chen, a cognitive social development specialist at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, works with kindergarten and primary school children in Hong Kong, Taiwan and America.

She said the Hong Kong education system’s competitiveness from kindergarten right up to university, was damaging for young people.

“There is a sense that there is a sequence of hoops to jump through,” she said. “This early talk of failure, if a child doesn’t get into a particular school, is very concerning to me. Children are very sensitive in their early years. They will pay attention to what the parents and teachers are saying.”

Chen advised parents to spend as much “quality time” with their children in their early years as possible in order to aid their development, but added this did not mean the activities done with children, especially for working parents, need to be high energy.

“It could simply be reading a book together, having dinner, talking or giving your child a bath,” she said. “It is good to make sure it is quality time, rather than just the parent writing work emails while the child does his or her homework.”

No time for outdoors

The intensive curriculum in public schools was blamed as the culprit.

Special needs education teacher and mother-of-two Alex Von Etzdorf works part time as a teacher of Capoeira, a Brazilian martial art which incorporates elements of music and dance for adults and children as young as three.

She said her young students at the Hong Kong School of Capoeira learn social and language skills because the activity required the use of Portuguese words and phrases, and that she only introduced the more competitive elements of the martial art for older children.

“You are teaching your child that it is okay to tumble and fall down,” she said. “It’s so energetic and kids really need that at the end of a day. It gives them an identity outside of school that is not education based. As a mother myself, my aim is just for my children to be happy, which can be hard in Hong Kong.”

Despite the worrying trend, social development specialist Eva Chen said Hong Kong children were faring relatively well in their early years, given the pressures, but there were parents who thought that more playtime was needed.

“[Kindergarten children] are fairly disciplined, mature and smart,” she said. “It is clear that parents don’t think the system is ideal but there is a collective helplessness about it. There is a desire for a more play-based education. On average, there is more school work than in other countries I’ve work in.”

We are all different

Children with learning difficulties are perhaps some of the most vulnerable to slipping through the cracks in the current system.

Since 2015, the Education University of Hong Kong (EdU) has been running a four-year early childhood development project, costing about HK$90 million in total, with support from the Simon K.Y. Lee Children’s Fund.

Known as the 3Es Project (early prevention, early identification and early intervention), the school-based programme aims to identify learning difficulties in children at an earlier age, and help schools to intervene earlier with better learning support.

Professor Kevin Chung Kien-hoa, head of the department of early childhood education at EdU, said that an estimated 20 per cent of children in Hong Kong had social and emotional problems which could be holding them back at school. But he emphasised that some psychological conditions were exacerbated by other factors such as a dysfunctional family environment.

He said he was confident that the government and its schools were making greater strides to better accommodate children with special educational needs, and this would improve their general well-being.

“We need to ask how we can modify the system for these children,” he said. “If you want to be a teacher, then you have to show compassion and love for all students.

“Parents can be in denial about their child’s special educational needs at first, but I tell them it is a blessing; we are all different. I tell them to try to find a school which fits the child, not the other way around”.

Too much technology?

International studies have also shown that children are becoming addicted to technology from an earlier age, and are increasingly multi-tasking, meaning they might be watching television, using their phones and doing their homework simultaneously.

This has the potential to reduce their attention spans and lower their moods.

In 2013, a survey of 500 young Hongkongers by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups, a service organisation for young people, found that 90 per cent of youth were addicted to their phones, and they sent and received up to 221 text messages per day.

A Connected Life study found that the average millennial in Hong Kong, aged 16 to 30, spent 2.8 hours a day on their mobile devices, as part of a survey of 60,500 internet users worldwide by global research consultancy TNS, the Washington Post reported in May last year.

The study suggested parents could control their children’s use of electronic devices by: declaring tech-free zones and times; checking the age ratings of products; discussing their media use from time to time; encouraging them to minimise multi-tasking; becoming a role model on technology use; and helping them seek professional help from a psychologist if necessary.

Hong Kong lawmaker Michael Tien Puk-sun, who represents the constituency of New Territories West, last year raised the issue of how electronic products were affecting Hongkongers.

He told the Post that he thought the government and parents needed to work harder to encourage children to live “a more balanced life”.

Despite this, academics in Hong Kong have defended the use of video games as a useful part of a child’s overall development.

Professor Patrick Lau Wing-chung of Baptist University’s department of physical education said video games were a “common lifestyle activity” which should be embraced rather than resisted.

But he said there was a need to differentiate between active and non-active video games, and encouraged players to try simulation games such as boxing on the Nintendo Wii, in which actual physical exertion was involved.

He cautioned that video games should not be seen as a substitute for exercise, and players should be careful not to strain their eyes from excessive gaming.

Meanwhile Samuel Chu Kai-wah, associate professor at HKU’s faculty of education, said he supported the idea of “gamification” – the application of gaming elements to teaching and learning.

He said that according to neuroscience studies, playing certain action games for 30 minutes a day over a period of two months could actually stimulate brain growth and boost memory, sight, hearing and decision-making skills.

But Chu also emphasised that this should be done in moderation.

Additional reporting by Raymond Yeung

WHAT OUR YOUTH ARE SPENDING TOO MUCH AND TOO LITTLE TIME ON...

TOO MUCH

Mobile phones: In 2013, a survey of 500 young people by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups found that 90 per cent of them were addicted to their phones and they sent and received up to 221 text messages per day. Doctors have emphasised that overuse of mobile phones could have adverse effects on psychological and physical development in the young, particularly if parents are unaware what content their children are accessing on smartphones.

Studying: In 2016, a survey found almost half of Hong Kong parents thought their children should spend at least seven hours a week studying over the summer holidays, which was less time than they planned to spend with their children. The Institute of Family Education emphasised that parents should socialise more with their children, but it admitted that Hong Kong’s long working hours were proving to be a big obstacle.

Junk food: About one in five Hong Kong children is obese, according to a government report in 2016. Bad diet and low levels of exercise have been blamed for the trend.

Video games and television: In 2016, the government revealed there had been a rise in the number of children developing myopia or near-sightedness, prompting further warnings from doctors about young people being overexposed to electronic devices.

Social media: Youngsters with relatively weak mental health spend more time on social media compared with other age groups, a survey for Mental Health Month in 2015 found. Less happy young people were revealed to be spending between four and 5 ½ hours a day on social media.

TOO LITTLE

Exercise time outside while at school: In 2016, it was revealed that some Hong Kong schoolchildren were being given less time outside for exercise than the city’s prisoners, according to Dr Robin Mellecker of the HKU’s Institute of Human Performance. A comparison between primary schools and prisons showed pupils got 295 minutes a week outside, compared with 300 minutes a week for prisoners. The Education Bureau requires primary and junior secondary pupils to spend at least 80 minutes a week doing physical education, while prisoners are given 60 minutes a day outside.

Conversation with parents: A survey this year by Chinese University found one in five Hong Kong parents chatted to their child less than once a week. Researchers suggested the trend could be affecting children’s performance at school and their general well-being. The city’s long working hours have been blamed for the dearth of communication.

Sleep: Hong Kong schoolchildren are going to bed too late, studies have shown. Doctors warn that children should go to bed before 10pm in order to aid their intellectual and emotional development. According to the US National Sleep Foundation, children aged three to five, six to 13 and 14 to 17 should get 10 to 13 hours, nine to 11 hours, and eight to 10 hours of sleep respectively.