Why Shanghai’s best-known liberal bookshop is closing down

Authorities forced cancellation of seminars at Jifeng Bookstore on topics ranging from South China Sea to constitutionalism

The owner, founder and customers of Shanghai’s best-known liberal bookshop are counting down the days to its closure as ideological control in China becomes stricter.

The Jifeng Bookstore’s last branch in the city, which opened at the Shanghai Library metro station four years ago, is due to shut its doors at the end of January, when its lease expires.

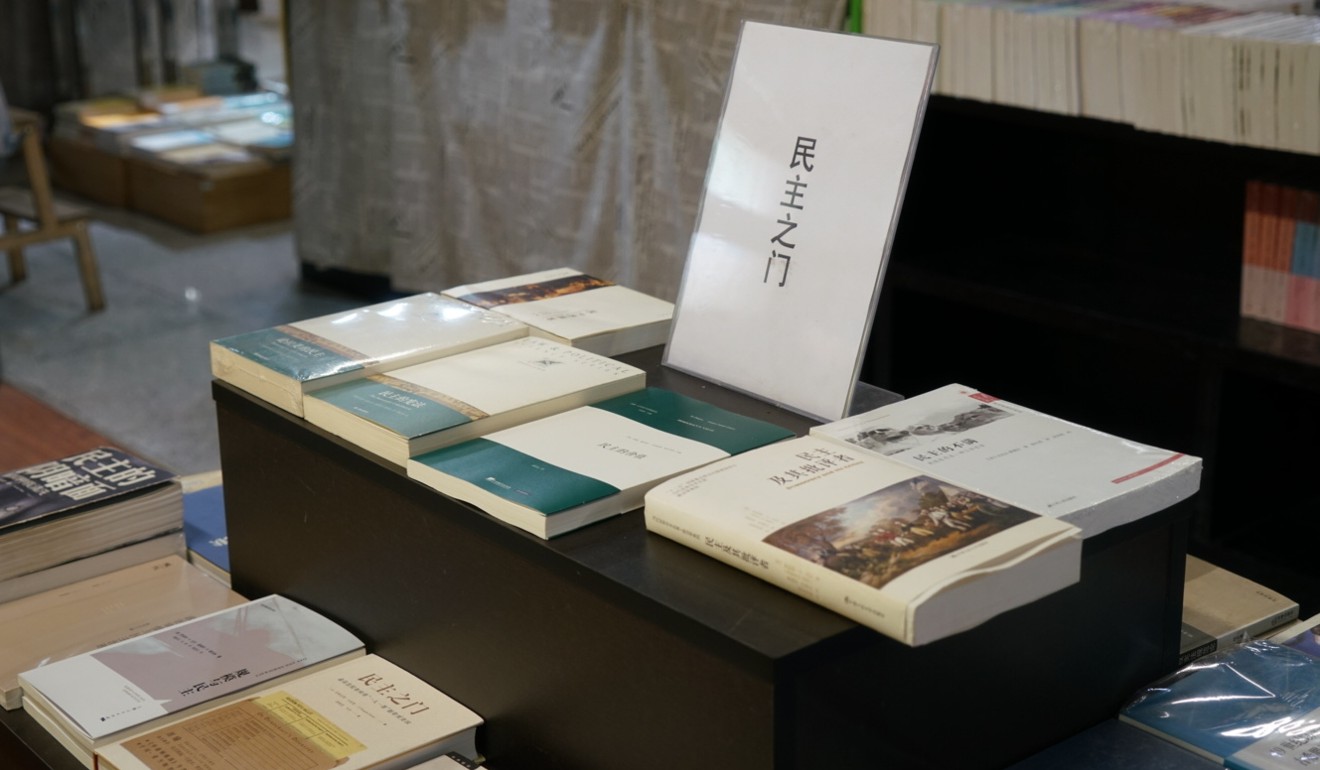

Long regarded a cultural landmark in China’s financial capital, Jifeng is known for its high-quality academic books on politics, philosophy, law and history, topics that are also explored by well-known scholars at regular seminars held in a large room at the shop.

Yu Miao, who bought a majority stake in Jifeng five years ago from founder Yan Bofei, said the library had decided to resume the premises for its own use and he had encountered “non-commercial” interference that had stymied efforts to find an alternative location.

“Some projects, including cultural/creative centres, invited us to open a bookshop at a favourable price or even rent-free,” said Yu, an entrepreneur in his mid-40s. “But the local culture departments made it clear they did not want Jifeng to move in when the landlord attempted to apply for a licence.”

Yan opened the first Jifeng Bookstore at Shanghai’s South Shaanxi Road metro station in 1997 and went on to open a string of other branches over the next decade or so. But rising rents and decreasing sales due to competition from cut-price online booksellers eventually forced their closure.

The selection of books for sale on Jifeng’s rows of black, wooden bookshelves still reflects Yan’s tastes. The former Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences philosophy researcher, now in his 60s, said “every book has values and a stance”, as did the booksellers who chose them, and he highly recommended speeches on liberalism, propositions such as constitutionalism and solid research on current politics.

“Our original target was very simple: we wanted to disseminate some progressive knowledge,” he said. “But those simple thoughts were misunderstood and probably regarded [by the authorities] as a base for opponents.”

Jifeng’s existence has been threatened before, in 2008 and 2012, when high rents at South Shaanxi Road prompted doubts about its future and public campaigns of support. A slogan from the 2008 campaign complained that the metro station could “only accommodate Haagen-Dazs, not [German philosopher Juergen] Habermas”.

But the Chinese authorities have further strengthened ideological control since Xi Jinping became Communist Party general secretary in 2012.

Zhang Xuezhong, a Shanghai-based scholar, said Jifeng’s impending closure was in line with a series of moves by the Chinese authorities to tighten ideological control.

“It has a negative impact on Shanghai’s image as an international hub but the authorities are more concerned about political stability,” he said. “They don’t want to see freer social or cultural events.”

Jifeng used to hold seminars at its old South Shaanxi Road headquarters but the frequency picked up after the move to the Shanghai Library metro station in 2013, with 150 to 200 events held every year. Objections by the authorities have resulted in roughly half a dozen cancellations a year.

Five seminars were called off last year, on topics ranging from the South China Sea to constitutionalism and the fate of entrepreneurs and intellectuals in modern China.

Two seminars cancelled this year were to have been led by historian Qin Hui and law professor Tong Zhiwei. Qin planned to give a lecture on issues arising from globalisation while Tong was scheduled to talk about reform of the mainland’s supervision system.

Qin, a history professor at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, attracted attention at the end of 2015 when his book Out of Imperialism, on the history of China’s attempts to form a government that abided by the constitution, was pulled from mainland bookshop shelves without a reason being given.

Government pressure appears to be mounting, with five seminars called off in less than two weeks.

“After we send out the notices on seminars, the authorities would pay attention to them and call me if they think it is inappropriate,” Yu said. “They would say the topic or the speaker has some problems, but not explain those problems.”

Chow Po-chung, an associate professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who has held two seminars at Jifeng, said he opted for milder topics so they could proceed smoothly.

“I know some seminars by scholars were halted previously,” he said. “I planned to talk about political philosophy and freedom but picked a mild, literary topic as I worried it would be halted.”

Yu said the authorities had accused the bookstore of engaging in “enlightenment” in recent years.

“Maybe they have concerns about such a place, where people can discuss and rethink many social issues, and whether this will break through what they promote and the constraints on thought they impose on you,” he said.

Chow said the seminars had also supported the growth of civil society and the pursuit of a better society.

“All the actions of civil society need moral resources and knowledge, including overseas experiences, historical references and learning from philosophy,” he said, “The question is where the knowledge comes from and where we can discuss it. You can see there’s almost no place in Shanghai apart from Jifeng.”

Yu Shiyi, a Jifeng fan who’s studying for a master’s degree at East China Normal University, said the bookshop’s closure would leave a hole in many people’s lives.

“For many of Jifeng’s readers, it has become a part of their life and attending its seminars on the weekend has become indispensable, just like eating and watching movies,” he said. “It’s very disappointing for intellectuals.”

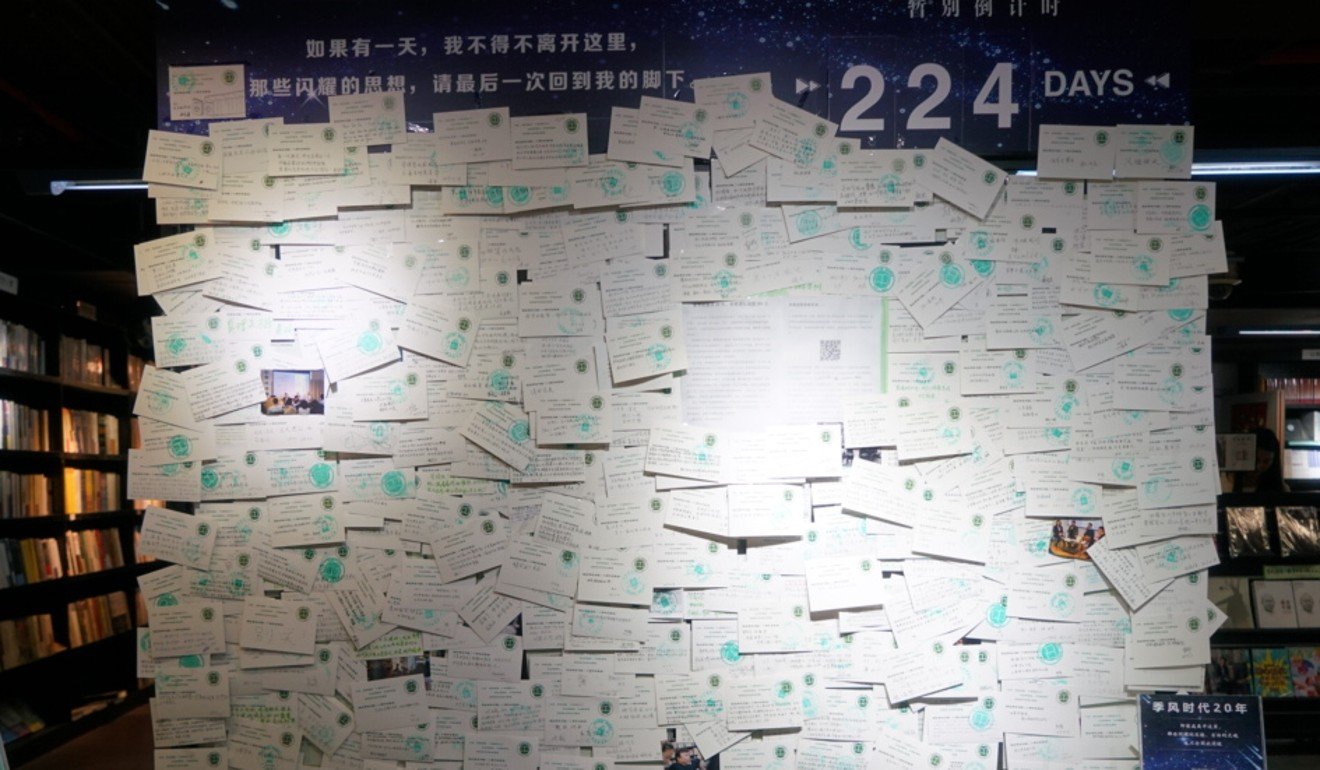

Jifeng fans have expressed their feelings about its closure in notes posted on a big board at the entrance to the bookshop, which also counts down the number of days it has left.

“The days were busy and repetitive at the metro station but time could stop because of the bookstore. I wish it could become an eternal landmark, just like one of my old friends who never separate,” one note read.

Another said: “Persist in independent thinking and a sense of democracy. Jifeng promoted social progress. Will always support you.”

Jifeng is holding a series of 20 seminars before its closure, with topics including Chinese philanthropy, education and China’s 1911 revolution, but some of its posts about them on the WeChat messaging service and Weibo microblog platform have been censored.

If all goes according to plan, Jifeng will not disappear from the mainland market altogether, with Yu Miao planning to open Jifeng Bookstores in other cities in eastern China. But, he said, until he saw the authorities’ reaction to the Jifeng sign going up on the opening day of a new shop, he would not know whether those plans would ultimately bear fruit. The plans were already in place when Jifeng announced on April 23 – World Book Day – that the days of its Shanghai store were numbered.

And Yu Miao said he would be willing to open a Jifeng store in Shanghai again if the authorities relaxed their grip, because such a venue was essential for society and culture to develop.

“Let’s see how long the contrariness and absurdity can be maintained,” he said. “In my opinion, it won’t last for long.”