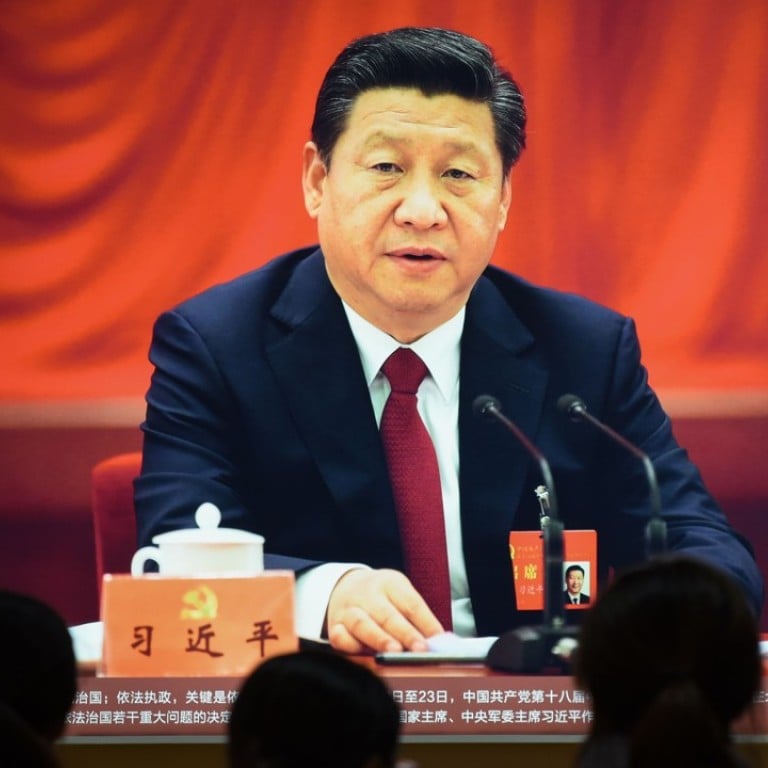

Reform or repression: what will the next five years bring for China?

David Shambaugh says in dismantling the old power bases, Xi Jinping has also severely weakened the bureaucratic institutions built up to prevent the over-concentration of power in one man

While the narrative of a strong and forward-moving China will be prominent, a variety of unresolved questions and issues underlie the veneer of unity and purpose that the congress will present to the world.

Concerning top party personnel, there are a number of uncertainties, given that roughly half of both the Central Committee and Politburo members will change, as well as five of the seven Politburo Standing Committee members. All analysts anticipate many of these top positions will be filled by Xi’s acolytes – mainly men who previously worked with him in Zhejiang or Fujian.

Friends in high places: Xi Jinping’s determined path to control

What does this mean for China’s political system and what kind of ruling party has the Communist Party become? Given Xi’s all-powerful persona, China’s political system has reverted to a patriarchal-patrimonial system – a form of governance where power rests with the imperial-type leader and not with institutions. Sociologist Max Weber identified this as “traditional” and “feudal” patrimonialism – as the ruling party or monarchy becomes hegemonically dominated by a single ruler, rather than institutionally dispersed into a meritocratic and enfranchised bureaucracy. Xi’s total dominance of the party, state and military personifies Weber’s patrimonialism.

When we say ‘new order’ of the Chinese Communist Party, what exactly are we talking about?

Is this good for China and the Communist Party? Recall that, beginning with Deng Xiaoping in 1978, the party has very consciously sought to disperse power away from an almighty ruler. Deng was quite explicit that the over-concentration of power in one man – Mao Zedong – was what had led China down a disastrous path for two decades, from 1956 to 1976. To rectify this malady, for the past four decades, the party has sought to devolve power within the central party, separate party from government, and devolve authority from Beijing to provinces and localities. The whole decision-making system was to be based on consultation and collective decision-making, following technocratic expert input. Xi has reversed all of these norms.

Moreover, as intended, the anti-corruption campaign has ruthlessly destroyed various factions in the party, state, military and internal security apparatuses. Many “iron rice bowls” have been shattered. Surely, this has severely stressed these institutional systems, which has resulted in the “freezing up” of these bureaucracies, and the technocratic mode of policymaking.

Does Chinese leader Xi Jinping plan to hang on to power for more than 10 years?

Perhaps most noteworthy has been the shake-up, shakedown and shakeout in the military – where over 4,000 officers, 100 generals, and four Central Military Commission members have been relieved of their duties. Taken together with the sweeping reorganisation of the People’s Liberation Army high command that Xi launched in January 2016, the military may be reeling from these twin pincers.

Overall, these purges have affected more than 500,000 individuals in China and they surely have taken their toll on morale throughout the country’s elite – although the campaign is very popular with the masses. Ironically, Xi’s attempt to strengthen the party may, in fact, have further damaged it as an institution. The party is now akin to a military organisation – where orders are given and followed, with no operative feedback mechanisms or what is described as “inner-party life”.

Being Xi Jinping: the difficult art of juggling growth and control

China’s top graft-buster Wang Qishan: will he stay or will he go?

If Wang does not become premier, expect continued slow and hesitant implementation of economic reforms, continued credit-fuelled fiscal stimulus and fixed-asset investment into infrastructure, continued ballooning of corporate and local government debt, and a deepened “middle-income trap”. If Wang does get the premiership, it will be the best thing for China – as more robust implementation of the Third Plenum package can be expected. No one else in the leadership has the political clout, combined with deep knowledge of the economic system, to roll out the reforms.

The party’s severe political controls domestically and its hesitancy on economic reforms are juxtaposed with a very confident China on the world stage

Party congresses are usually much more about continuity than change, as they largely recap the past five years. Nonetheless, the general secretary’s work report will offer a comprehensive overview of various policy arenas and could indicate some new policy departures.

This raises a final question: the contradiction between a seemingly insecure party leadership reflected in its internal policies, and a very secure leadership on external foreign policies. The party’s severe political controls domestically and its hesitancy on economic reforms are juxtaposed with a very confident China on the world stage. Will the post-congress leadership begin to exhibit confidence domestically to open up the polity, society and economy – to match China’s confidence internationally? However wishful, don’t bet on it.

David Shambaugh is professor and director of the China Policy Programme at George Washington University and author of China’s Future