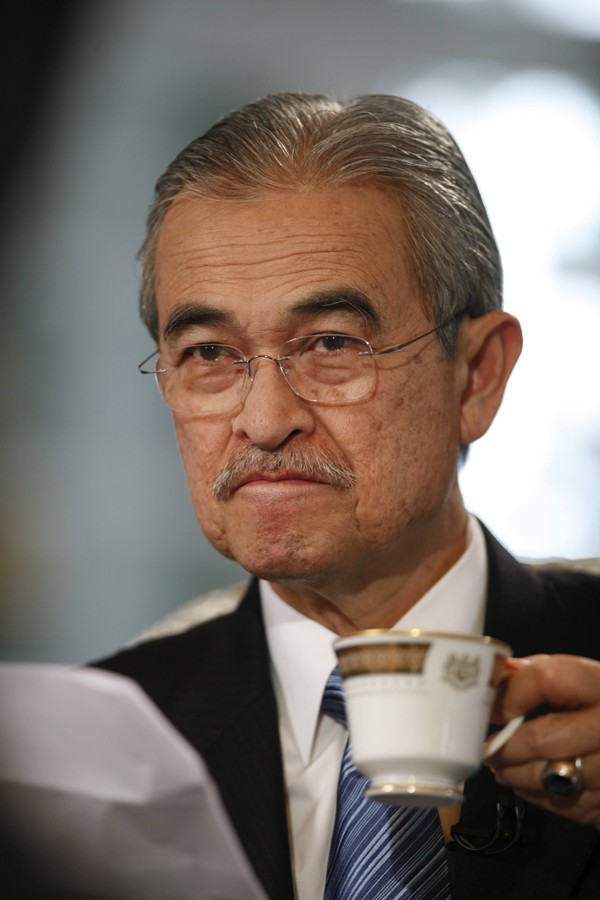

After 18 years, why is Malaysia’s Mahathir apologising to Anwar?

The 91-year-old former prime minister has indicated a willingness to support the deputy he sacked at the height of the Asian financial crisis – and who is currently in jail on sodomy charges

No one was expecting an apology from Mahathir Mohamad to Anwar Ibrahim at all.

When Mahathir first showed up at the trial of Anwar in September 2016, in the latter’s legal challenge against Malaysia’s National Security Council Act – legislation that empowers any incumbent prime minister to suspend the electoral process – eyebrows were raised.

Tongues were wagging that Mahathir would make amends for firing his one-time deputy when he was prime minister.

But days turned into weeks, and weeks into months. Nothing came. Mahathir still refused to express contrition.

To the surprise of many, the former Malaysian prime minister recently conceded to The Guardian in London that he had “governed Malaysia far longer than needed”, leading the way for two subsequent prime ministers who appeared to be clueless about how to transform Malaysia.

In fact, they had made the country worse than when he left power in October 2002.

Abdullah Badawi, who ruled from 2003 to 2008, was famous for dozing off half an hour into any meeting, a problem which the former premier confessed to have shared with Mahathir prior to his appointment as the fifth prime minister.

Mahathir said he had erred, and that Anwar, whom he sacked in 1999 as his deputy prime minister – at the height of the Asian financial crisis – should have been allowed to become the fifth prime minister.

Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad on why he’s not ‘anti-China’

The former leader went so far as to say that if Anwar were pardoned by the king – Anwar is currently serving a five-year prison term for a sodomy conviction many believe is politically motivated – he would support him as the next prime minister.

His expression of remorse, both at the manner by which Anwar had been “unfairly treated”, was not merely an effort to ingratiate himself with the opposition front, now led by Anwar’s wife, Wan Azizah. It was also a candid recognition of the relative strength and power of the opposition. Although Mahathir, upon arrival in Kuala Lumpur on Friday, said that what is “past is past” – that there was no need to frame his interview with The Guardian as an admission of guilt in any form – it was clear that he had shown deep regret.

Mahathir, with five wide-margin electoral victories under his belt, knows that the task to remove Najib from power is almost impossible. To do so requires the forging of strategic electoral pacts with old enemies. Anwar is one of them, if not the key one.

At 91, time is not on his side. Though now in brisk health, he had a heart-bypass operation in 1984 and, as a trained medical doctor, knows that each day forward is a gift.

His new political party, Bersatu, which means “unity” in the Malay language, does not command resources like the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO).

By conceding his past mistakes, Mahathir immediately clears the way for his party to work closely with the national opposition front, which is formed by Anwar’s Justice Party, the Democratic Action Party, and even the Amanah Party, a splinter party from the conservative religious entity the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party.

Fake news and a 30-year plan: Malaysia’s Najib takes aim at Mahathir

Of the 222 constituencies in Malaysia, 119 are considered rural, which presents a challenge for Mahathir.

First, he lacks the manpower to get rural constituencies to vote for the opposition en masse. Thus, he needs other opposition members to lend his party a helping hand.

Second, in order to break the electoral logjam, he had to put aside his ego for an alternative approach. He chose to forego his pride so that the opposition machinery would inch forward again in time for a snap election in October or by the middle of next year.

Third, by owning up to his shortcomings, Mahathir humanises himself and Anwar as a genteel but formidable pair.

But Mahathir’s show of contrition is also important in two other respects.

To begin with, it could make Malaysia’s rural heartland long for the halcyon days of the 1990s, when the gross domestic product of the country was booming. It suggests to them that what was once possible in Malaysia can be once again – providing Najib is first defeated, and then removed.

To be sure, no one knows if his penitent approach can move a whole country. It is clear, however, that based on Mahathir and Anwar’s opposition pact, both hope it is a good start.

The opposition will need all the sway and clout of both figures to drive a stake through the heart of the government.

The task to convince the voters it’s time for a change remains daunting. Under Najib, Malaysia’s economy is still expected to grow at a clip of 5.1 per cent, even though much of the gain will be neutralised by a weak ringgit.

But most Malaysians, after several revelations from the US Department of Justice about the financial improprieties of 1MDB, are nauseated by the excesses of the prime minister and his inner circle.

In the civil proceedings, sordid accounts of how billions of dollars were laundered in more than six jurisdictions have been revealed.

Tens of millions of US dollars were spent on gems and diamonds, some of which diverted to the personal possession of the wife of the “Malaysian Official One”, widely known as the prime minister’s wife Rosmah Mansor.

The opposition, together with Mahathir, has launched a road show to showcase these scandalous details to the rural people of Malaysia in order to win hearts and minds.

If the message gains traction, especially in the 54 Malay constituencies in a federal land development scheme that have been the mainstay of the UMNO party, the pillars of support could begin to weaken.

Why Malaysia’s hopes for a post-racial politics are fading – even if Mahathir is not ‘anti-Chinese’

Even so, such a strategy comes with significant risks. If the government loses the 14th general election, Najib would have to concede that he has lost the trust of the people. If push comes to shove, he may invoke the National Security Council Act to suppress opposition. No one knows if the state is capable of orchestrating a random act of violence to stay in power, but that is also a possibility. Indeed, Mahathir appears to anticipate such moves by Najib, warning his opposition colleagues that they might face arbitrary arrests.

Saying “sorry” to Anwar, belatedly as it was, will have some tactical impact. But Mahathir may be sorrier still if Najib’s government, sensing a real threat to its power, launches a major crackdown on the opposition.

Either way, Mahathir and Anwar are both locked in the twin horns of Malaysian politics, complete with their draconian implications. ■