Hospice and palliative care services in Hong Kong: how to access them, and why we need to talk more openly about death

Demand for end-of-life, palliative and hospice care in Hong Kong is outstripping supply. Knowing what the options are is essential to ensuring loved ones die in peace, and so too is talking frankly about dying

The generous souls engaged in the service of hospice and palliative care in have a mission: to add life to days when they cannot add days to life.

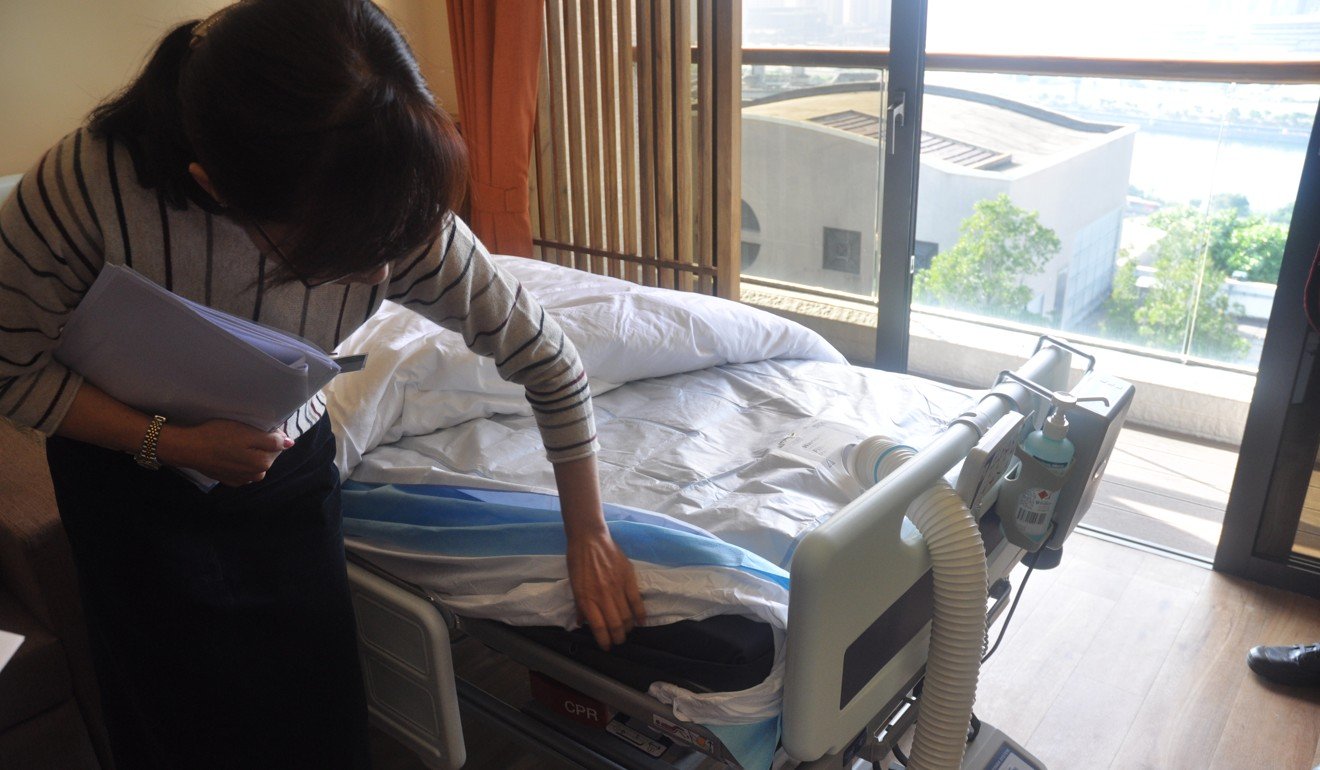

For Connie Chu, chief operating officer of the Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care (SPHC) in Hong Kong, a that means helping people feel more comfortable as they approach death.

“It’s time to see how [they can] live better within a limited period of time, how to get rid of harsh treatment, how to make a patient comfortable, and how to make good memories for the whole family.”

Father Luigi Bonalumi, a parish priest in Tai Po who counsels the dying, says Hong Kong society ought to talk more openly about death so that people can die more peacefully. He recalls how important this was for a woman he helped a year ago.

The struggle for Hong Kong’s old and sick to die with dignity

“She was a principal in a school and she had cancer. Towards the end of her life she told me that walking this path was difficult. She felt pain and suffering. She had thought it would be easier, but [after talking about it] she accepted it and went in peace.”

With rising cancer incidence and a growing elderly population – creating more cases of dementia, chronic illness, poverty, loneliness and despair – end-of-life care such as pain management and spiritual counselling is in increasing demand in Hong Kong. Such support, though, is not always easy to access.

Currently 16 hospitals under Hong Kong’s Hospital Authority provide end-of-life, palliative or hospice care services, with a total of about 360 beds. This is comprehensive care for the terminally ill that includes control of a patient’s symptoms or pain, psychological counselling for patients and their families, and spiritual support for those who want it.

New Hong Kong group set up to push for end-of-life care for children

Apart from the Hospital Authority, The Haven of Hope Christian Service offers 124 beds, while the Jockey Club Home for Hospice (JCHH) – a part-public, part-private facility operated independently by the Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care, which opened late last year – offers 30 beds.

Demand, however, far outweighs supply, and many of Hong Kong’s dying miss out on quality end-of-life care.

Those that end up in hospice and palliative care usually stumble upon it, Chu explains, or discover the services only after being unable to tolerate the side effects of hospital treatment. She remembers an English woman whose daughter transferred her to JCHH from one of Hong Kong’s top hospitals.

“She received the best treatment [at the hospital], but she couldn’t handle the pain. The doctors tried everything. Eventually her daughter couldn’t handle her screaming. She felt guilty because her mother was, as she described, ‘being tortured’. Finally, a nurse at the hospital referred the patient’s daughter to us.

“They didn’t know that a patient’s pain could be controlled. After our doctor adjusted her medication and helped her manage her pain, her condition began to change. The daughter’s description of her mother’s pain went from torture to a meowing cat.”

VIDEO: For Hong Kong’s terminally ill patients, palliative care provides relief for their last journey

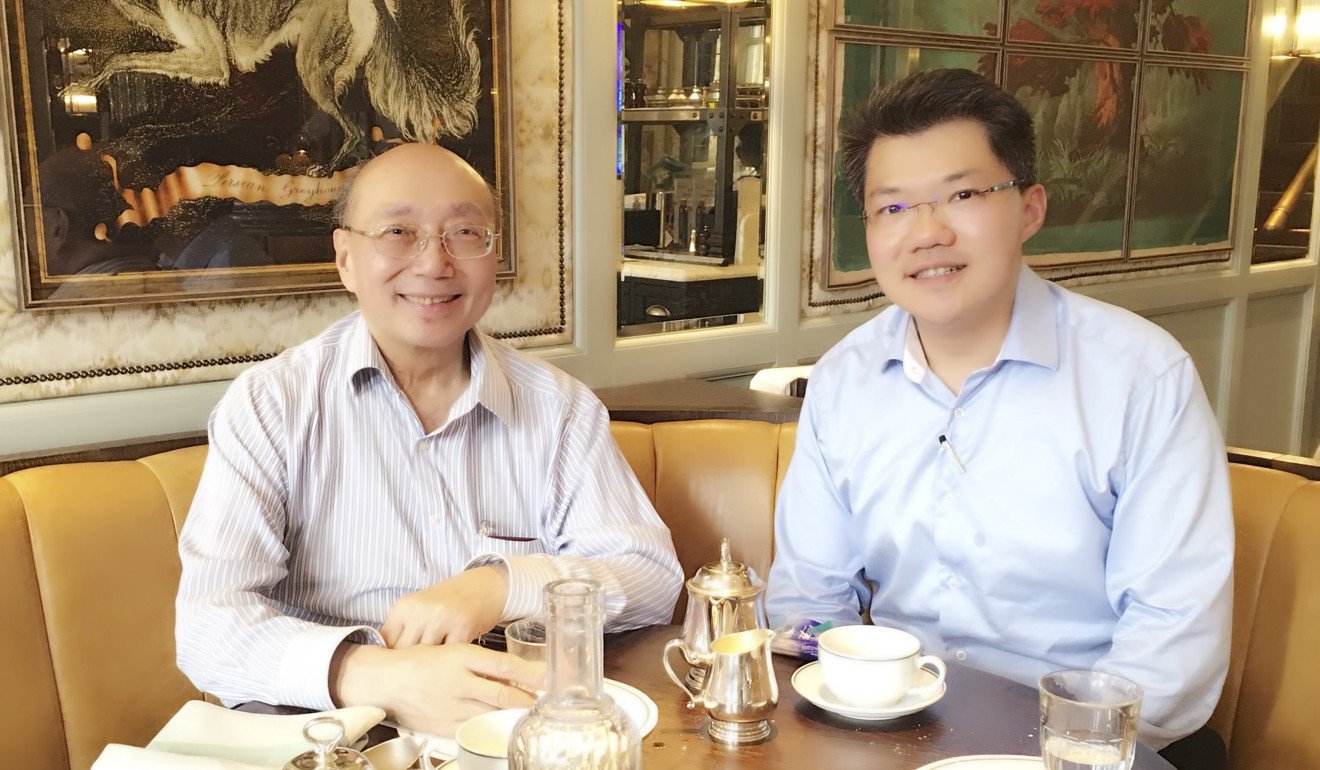

Dr Christopher Hui is a UK-trained respiratory and critical care specialist who is on the board of SPHC. He says that shifting to end-of-life care presents many challenges not just for patients and their families, but for clinicians too. Clinicians responsible for treating patients at the end of their life often lack adequate training and experience to guide decisions and to deliver bad news to patients and their families.

“Within Hong Kong’s medical community, it is fairly apparent that we have only recently begun to develop a focus on the psychosocial and spiritual well-being of our patients,” he says.

When Hui’s father, who has had cancer for a number of years, started to deteriorate rapidly, he was transferred to JCHH for care. The hospice staff helped to support his family members so his father could spend his remaining days in a home environment cared for by his family.

“Hospitals can look after immediate problems, but they will not take care of an individual’s home needs,” Hui says.

A Hong Kong centre to warm the hearts of cancer sufferers

When Hui’s situation changed from doctor to family member of a terminally ill patient, he felt first-hand the need for a caring, patient approach that a hospice environment offers – especially the willingness of the care team to help solve what seemed like simple problems.

“Mum asked how she should rearrange things at home to help his personal and bathing needs. We installed some appliances and equipment in the bathroom – like handles and rails. The quality of care isn’t just in the drugs or treatment. It’s about the patient getting exactly what they need when they need it, and being safe to manage in the environment they’re in, whether it’s in the hospital, hospice or at home.”

Chu says it can be difficult to access the correct end-of-life care through the Hospital Authority, so those that want to make use of public services must make it clear that the patient no longer wants active treatment. Referrals for palliative or hospice care under the Hospital Authority must come from a doctor, and each case is rigorously screened.

We have worked out solutions before where a patient may come to us for a five-day break in between their chemo, for example, and then go back to the hospital for the medication they need

JCHH, which operates independently, can be contacted directly through its hotline, by email or in person. Where available, referrals are preferred, especially from clinicians. Some patients may be referred by a social worker.

There are four circumstances in which hospice care is most needed: when active treatment stops and family members require training to settle the patient at home; for symptom and pain control; for respite care, to give family members a break from looking after the patient; and the dying phase, when the patient may choose to return to the hospice.

Inside Hong Kong’s only English-speaking care home – a far cry from government-run facilities for the elderly

A nurse will assess the patient and family members to see if they understand the services. This can include inpatient and outpatient services (for example help with caring for the patient at home), or a mixture of both.

“We have worked out solutions before where a patient may come to us for a five-day break in between their chemo, for example, and then go back to the hospital for the medication they need,” Hui says. “This is because we’re unable to provide some of these agents from the hospice environment.”

Family and friends are key to helping the dying seek closure and go in peace and dignity. Chu says SPHC encourages clients to face death, discuss it with loved ones, and make an advanced care plan regarding their wishes before they become unable to speak for themselves. This plan should address things like the type of physical care they want, whether they have unfinished business at work or in family relationships, and whether they want a religious ceremony after death.

In Asia, these decisions are often made as a family. Unity is important, but conflicts can occur.

Chu remembers a son who requested the SPHC’s services for his dying mother, who had cancer. He had a sister, but she wasn’t involved in her mother’s care. The team sensed something was wrong, because the son took complete responsibility for his mother.

‘Free Hong Kong doctors to help dying patients end their days at home’

He did everything including bathing her, helping her to use the toilet and dressing her. They were very close, and he went to great lengths to maintain his mother’s dignity. But why wasn’t the sister involved in her care? SPHC decided to call her, to tell her that her mother was going to die.

“The mother and daughter were angry at each other,” Chu says. “The mother thought her daughter only wanted her money so she gave it to her son, but the daughter was upset that her mother gave up pursuing medical treatment. It was important that the mother saw that it wasn’t about the money.” The patient finally passed away with both her children at her side.

An important part of care involves looking after the people left behind. In Father Bonalumi’s experience, letting go can be hard. He still visits the husband of a lady who died last year.

“They were high school sweethearts, and did everything together. So now, after 80 years, he is alone. He tells me sometimes when he goes to the park he can feel his wife’s presence.

“We need to talk about the fact that there will be an exit, in a way. It’s important for everyone, not only for the person facing death. It has to be recognised and valued.”