When Big Brother gets God’s Eye: China tries to catch up on AI

Artificial intelligence viewed as next big thing in tech but also an ethical challenge

The all-seeing God’s Eye, a system that can hack into any camera and locate anyone, anywhere in less than four minutes is one of the stars of the two latest instalments of the Fast and Furious blockbuster movie franchise.

In China’s most innovative city, Shenzhen, two US-educated Chinese scientists have found a way to turn part of God’s Eye into reality – if the authorities allow them to insert a tiny chip into surveillance cameras.

With the chip, a surveillance camera can greatly speed up human facial recognition and spot a criminal suspect in a crowd in just a few seconds. It has proved effective in at least in one district in Shenzhen and, according to publicly disclosed information, has helped police crack hundreds of cases and find a number of lost children.

The firm, Intellifusion, is just one of the fruits of China’s efforts to become a global leader in artificial intelligence (AI), a technology that may profoundly change everyday life and that promises massive financial pay-offs.

China’s AI ambitions were emphasised at the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress in March and the message was not lost on the country’s biggest tech companies.

Beijing’s efforts to close the innovation gap with the United States have since been given a big boost, with billions of dollars invested in AI laboratories and projects.

Baidu president Zhang Yaqin says his company, China’s equivalent of Google, invests more than 15 per cent of its revenue in research and development every year, much of it on AI. It set up a national deep-learning technology lab in Beijing in March, drawing on the talents of its own AI experts and others from Tsinghua University, Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology.

Messaging and gaming behemoth Tencent recruited the former head of Baidu’s Big Data Lab, Zhang Tong, last month to lead a team of more than 50 AI scientists and 200 engineers at its AI lab, which focuses on computer vision, voice recognition, natural language processing and machine learning. Its AI Go program Yueyi won the Computer Go UEC Cup in Japan in March.

AI’s potential was demonstrated in January when DeepMind’s AlphaGo, playing under the name “Master”, won 51 online Go matches against some of the world’s best players. Go, a game at least 300 times more difficult than chess, is viewed as a good test of artificial intelligence because of its many permutations and combinations of moves. AlphaGo will be taking on the world’s top-ranked player, China’s Ke Jie, in a best-of-three series in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, next week.

According to recent research by UBS, AI could produce economic value of between US$1.8 trillion and US$3 trillion a year by 2030 in Asia─by introducing new product services and categories, cost savings arising from better products, lower overall prices and improvements in lifestyles.

Data provider i-Research predicts China’s AI market will be worth US$ 9.1 billion in 2020 after growing at an annual compound rate of 50 per cent.

That’s been encouraging growing numbers of overseas-trained Chinese researchers to flock back to the mainland to explore AI opportunities and industrialise their technologies.

China, with US$2.6 billion, ranked second globally in terms of investment in AI enterprises and start-ups last year, sandwiched between the US on US$17.9 billion and Britain on US$ 800 million, according to data from China’s WuZhen Institute think tank.

Intellifusion, a start-up founded in Shenzhen three years ago by two Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) experts – Chen Ning and Tian Dihong – who returned to the mainland from the United States, is one of the firms breaking new ground.

“The mainland market is the best choice in the world for talented research scientists to bring their AI technology from lab to life and make it possible for scalable AI products,” Chen said, while acknowledging there were more developed AI technologies and more experienced AI talent in the US.

“While there’s no doubt artificial intelligence is the new frontier, the foundation for the technology is still not mature.”

The winner would not be the one with the best algorithm, Chen said, but the one with the most data.

“In the AI sector, China is a fast starter,” he said. “The mainland market, with its huge population, means you can launch AI products quicker, collect more data and upgrade your algorithm faster, and then lower your cost to compete for bigger market share.”

US-based GPU maker Nvidia predicts there will be a billion surveillance cameras watching people around the world by 2020, presenting the massive challenge of working out exactly how to deal with that giant deluge of data.

That’s where an “intelligent chip” designed by Chen and Tian’s company, Intellifusion, stands to cash in.

The authorities in Shenzhen, dubbed China’s Silicon Valley, have invested in the start-up and given it other support. But some people have expressed concern about the privacy implications of the technology.

Around 100,000 public surveillance cameras across the city will be using Intellifusion’s chips by the end of this year. They enable police to identify an individual in just a second or two from a database of about 300 million people and most surveillance cameras in Shenzhen will be fitted with them by next year.

Chen and Tian worked together at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Centre for Signal and Image Processing 15 to 16 years ago. Their company now employs around 100 people.

Chief executive Chen, 42, said Intellifusion’s chip was much more effective than the traditional CPU (central processing unit) and GPU (graphics processing unit) chips.

“An effective front-end AI-powered chip for visual intelligence is a must in future, to make the machines not only see the world, but also understand the world and conduct local real-time processing,” Chen said. “Our chips in cameras can preprocess video data, detect and extract targeted facial characteristics, and translate them into arrays of binary data, which are uploaded to the cloud for final processing.”

Chen and Tian, who specialises in visual computing and led tech teams at Samsung and Cisco, decided in 2014 to resign from American tech giant employers and return to Shenzhen to start their own AI business.

Their decision, reached after two days of conversation, paid off the next year when they won an innovation competition for international talent under Shenzhen’s Peacock Plan, an ambitious city government programme to recruit and support top hi-tech researchers. They attracted more than 40 million yuan (US$6.3 million) in funding and subsidies from the Shenzhen authorities in 2015.

That success boosted their national profile and Intellifusion’s products are now used in more than 10 Chinese provinces and also in Malaysia.

In its A-round financing in March last year the start-up attracted US dollar investment in the eight-figure range from Chinese venture capital funds.

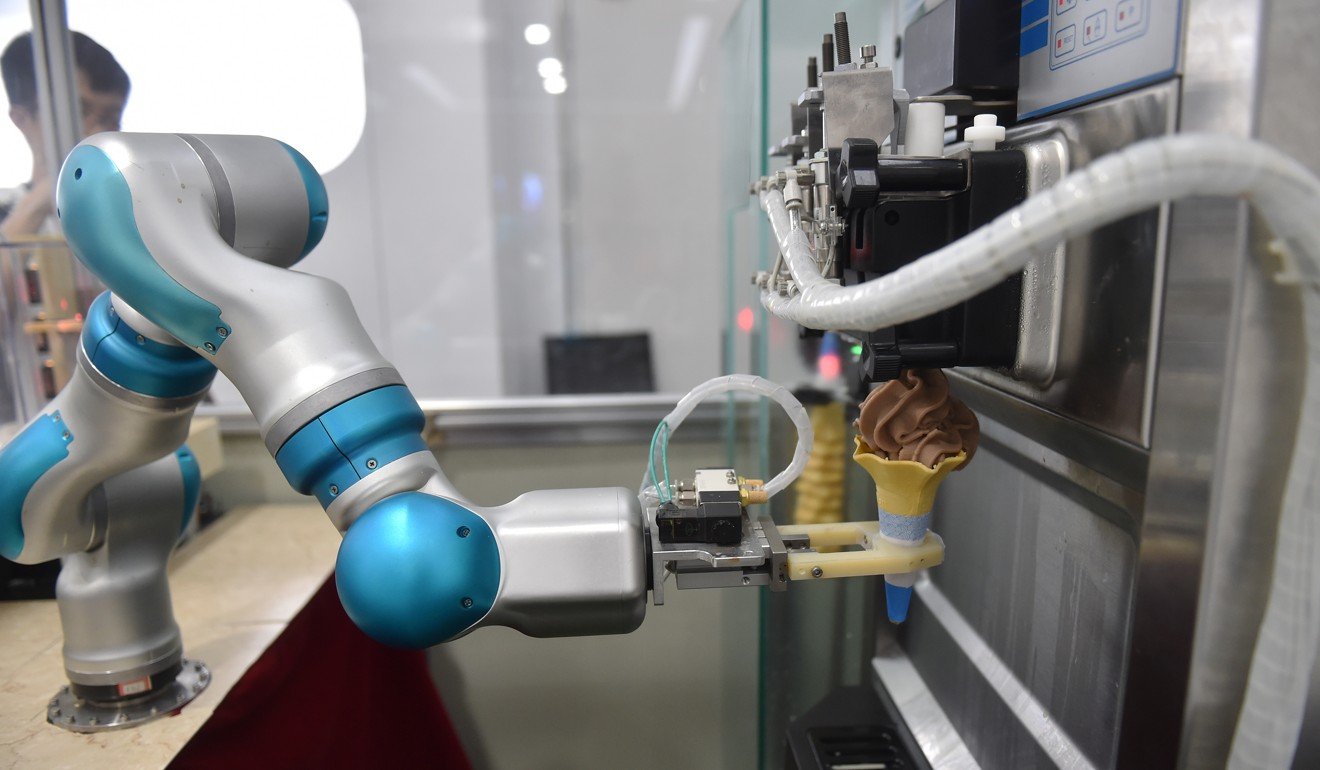

“Top-level Chinese AI experts are rich in advantageous resources in the mainland market,” said eSight Technology founder Dr Huang Bufu. With a PhD in mechanical design and automation from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, he’s founded a start-up in Shenzhen focusing on machine vision development for industrial robots in Pearl River Delta factories.

Huang said his company, with about 20 staff, had completed its first round of financing, with investment from several mainland venture capital funds.

“Based in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen, AI start-ups can reach various venture funds across the country and benefit from preferential policies from local government, not only for the projects and start-ups, but also for the human resources,” he said.

Huang said several friends who had earned PhDs in Hong Kong had decided to follow him across the border to explore the opportunities for AI start-ups on the mainland.

The flood of investment into AI on the mainland has spurred calls for public debate on the ethical and moral implications of technology such as robots, cameras with “brains” and autonomous cars.

“While governments make Intellifusion’s chips a hi-tech showcase in the cities, arming public surveillance cameras to make the cities safer, the rights to privacy of the citizens they track must not be forgotten,” said Wang Cairong, secretary general of the China Artificial Intelligence Robot Industry Alliance.

Chen said the AI tide could not be turned back, but better rules were needed.

“The governments and scientists need to sit down together to think carefully about how to revise current rules and laws for AI development,” he said. “In the future, the laws and the ethical rules will not just be for human beings, but also for human-computer interaction.”