‘Be silent or you’re next’: Maria Ressa posts bail, but arrest ‘puts all Filipinos at risk’

- The Rappler CEO is defiant on her release one day after being charged with ‘cyber-libel’ over a report her website ran seven years ago

- With an election looming, many suspect the case is politically motivated – and warn this is the thin end of the wedge

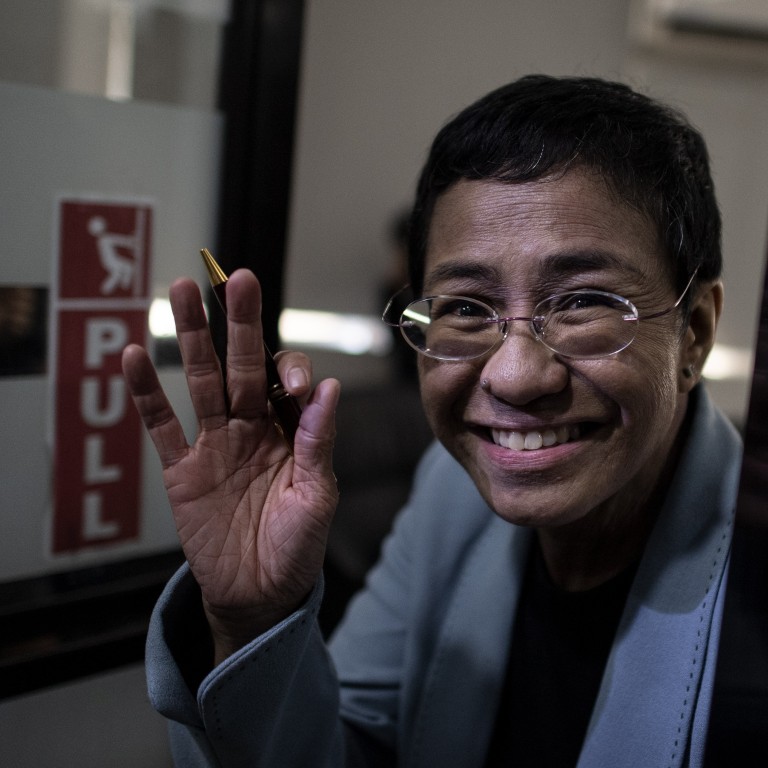

Award-winning Philippine journalist Maria Ressa emerged beaming and defiant after posting bail of 100,000 pesos (US$2,000) on Thursday, one day after her arrest on a charge of “cyber-libel” sparked international controversy and sent shivers through the country’s press freedom activists.

“We will not duck, we will not hide, we will hold the line,” vowed the CEO of news website Rappler, who has been charged over a report her company ran seven years ago.

Philippines arrests Duterte critic Maria Ressa on libel charge

“What we are seeing is death by a thousand cuts of our democracy,” said Ressa, adding that “someone told our reporters last night – ‘be silent or you’re next’.”

“I’ll be very transparent because I have done – nothing,” she continued, voice breaking, before warning Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra, “You don’t want to be known as the secretary of injustice.”

The article also claimed that Keng had once been under surveillance by the National Security Council regarding allegations of “human trafficking and drug smuggling”; that he was once investigated for murder; was close to some lawmakers; and that he “had contacts with the US Embassy at the time”.

Keng has denied all the allegations and says he was not approached for comment on the story – despite the article’s claims that the reporter Reynaldo Santos, Jnr had interviewed him the day before publication.

“Rappler, Ressa and Santos never attempted to obtain my side of the story on the crimes they wrongly imputed to me or to fact-check their baseless attacks against my name. I have never had a criminal record,” Keng said in a prepared statement issued shortly before Ressa’s release.

Keng said he was “deeply grateful to the Department of Justice” for charging [Ressa] and author Reynaldo Santos, Jnr of the crime of “cyber-libel” for “clearly defamatory statements against me” and noted that the charge carries a maximum of eight years in jail.

Fierce Duterte critic Maria Ressa is one of Time’s ‘Persons of the Year’

“In the end, this story is not just about an ordinary suit filed by a private and hardworking citizen to clear his name. It is, in reality, a test case on the how the Philippine legal and judicial system will fare against the dangerous precedent that is being set by one reckless and irresponsible member of the media and of the online community. If left unaccountable, Rappler, Ressa and Santos’ example of impunity will be emulated and replicated, and will destroy not just individual lives but our entire country.”

Santos, the reporter, left Rappler before the charges were brought. He has been charged alongside Ressa, but has not been arrested.

Keng’s lawyer Joseph Baguis told the South China Morning Post that Rappler had got in touch with Keng to confirm the licence plate number and ownership of a car mentioned in its report, but had not asked about other “illegal activities he was accused of”.

Baguis said he did not know why Keng had not filed a suit against The Philippine Star newspaper, which had in 2002 already published some of the allegations contained in the Rappler report. The Star had then claimed that Keng had once been suspected of links to various crimes including the murder of Manila city councillor Chika Go, smuggling fake cigarettes, and granting Chinese nationals residence visas for a fee. The Star’s allegations continue to be accessible online.

Muddying the case is that the law under which Ressa is being prosecuted – the Cybercrime Prevention Act – did not exist at the time of Rappler’s publication. It did not come into force until nearly two years later, in 2014.

Baguis told The Post that Keng’s lawsuit was premised on two things: One, “we feel cyber-libel is a continuing crime … because [the article] can be accessed anywhere anytime by any person. It’s different [to] ordinary libel, because a piece of paper can deteriorate, it can be lost, but this is always there.”

He also said cyber-libel no longer fell under a 1966 law requiring suits to be filed within one year of publication. “It’s the Department of Justice’s interpretation and we are supporting that. The prescriptive period is 12 years.”

However, University of the Philippines constitutional law professor Antonio La Viña told the Post the claims by the justice department and Baguis were “the most ridiculous thing”. Cyber-libel was “not a new crime, only a new way of committing libel”, he said

“No, it’s not a continuing crime at all [because if it is] you would then have an absurd situation where a news article from the 1800s that is reposted and reposted can still be punishable today,” he said.

La Viña said Ressa’s arrest continued a pattern of “twisting” the law which began with the jailing of Senator Leila De Lima for alleged drug trafficking.

“This is persecution, politically motivated, not based on law,” he said, claiming the case against Ressa was an attempt to “stop all dissent” before the May election.

Asked whether Ressa’s arrest could impact ordinary citizens, La Viña said: “You can be sure, you can now be subjected to this type of thing. If you post something – even five years ago, it’s still up there, nothing ever disappears from the internet. If your enemy gets this and [files a case] against you, you can imagine the opportunity for corruption.”