After the US midterm elections, don’t count on a Democratic Congress to soften Trump’s hard line on China

- David Shambaugh says a confrontational bipartisan consensus towards China has taken shape, as antipathy grows across different sectors of US society

- Until Beijing changes its repressive and aggressive policies and actions, the new American hard line can be expected to endure

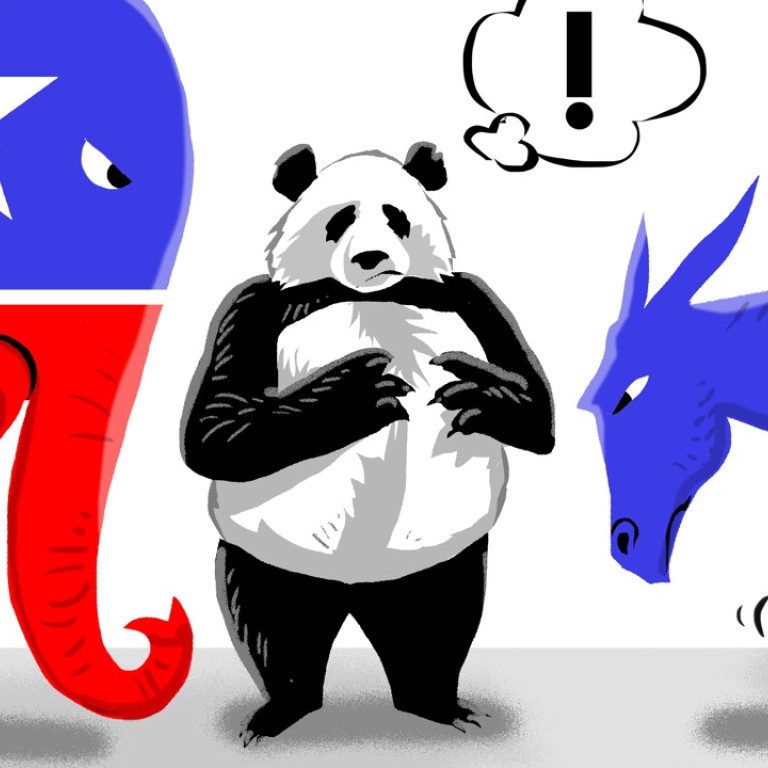

It is very unlikely that the election outcome will appreciably change the hardline China policy. The reason is because there now exists a quite strong bipartisan consensus for pursuing a toughened China policy.

Not only have Democrats and Republicans in Congress found consensus on the underlying rationale and elements of a hardened China policy, but it spans various professional sectors across the country.

If anything, if the Democrats take control of Congress (or even one house) the policy is likely to become ever tougher – as Democrats will push the Trump administration to be much more critical of China’s human rights abuses and increased repression.

Watch: US Vice-President Mike Pence accuses China of meddling in US elections

China’s internal security services increasingly keep foreigners under surveillance, and entry visas have been tightened. China’s increasing presence on the world stage began to bump up against the US in regions where China had never been before. And, finally, since 2017, concerns began to grow about China’s “influence activities” inside the US and other countries.

For all of these reasons and in all of these disparate professional sectors, a broad-gauge reaction against China has been building for several years.

This represents a new consensus – an anti-China consensus – in America. It is important to recognise that this trend has developed progressively and over time – not overnight.

Subsequently, the Trump administration has been formulating a “whole of government” and “whole of society” response to dealing with China toughly across a wide range of issue areas.

The 116th Congress may get even tougher on these and other issues.

This annual law, and many more China-related pieces of legislation now pending in Congress, share strange political bedfellows from across the political aisle.

Republican senators like Marco Rubio of Florida and John Cornyn of Texas find common concern and partner with Democrats such as Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Charles Schumer of New York and Patrick Leahy of Vermont. Similar cross-party anti-China political alliances exist in the House of Representatives.

With such deep antipathy towards China in the Trump administration and Congress, a real bipartisan consensus has not only emerged – it will probably be impossible to change, barring a reversal of the Xi regime’s internally repressive and mercantilist economic practices.

The history of the past five decades shows clearly that only when China is perceived to be liberalising internally and working with the US externally can a positive bipartisan consensus in favour of cooperation with Beijing be forged.

Absent a substantial reversal of Chinese policies and actions in a far more liberal direction domestically and more restrained direction externally, the new American hard line on China can be expected to endure indefinitely.

David Shambaugh is professor and director of the China Policy Program at The George Washington University in Washington, DC.