I translated Chinese writer Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’. Here’s why he never caught on in the West

- Graham Earnshaw, who translated The Book and the Sword, says the late author’s work had deep roots in Chinese history, language and nuance

- Cha’s lack of acceptance abroad was ironic, considering his huge leap in the direction of Western literary methodology

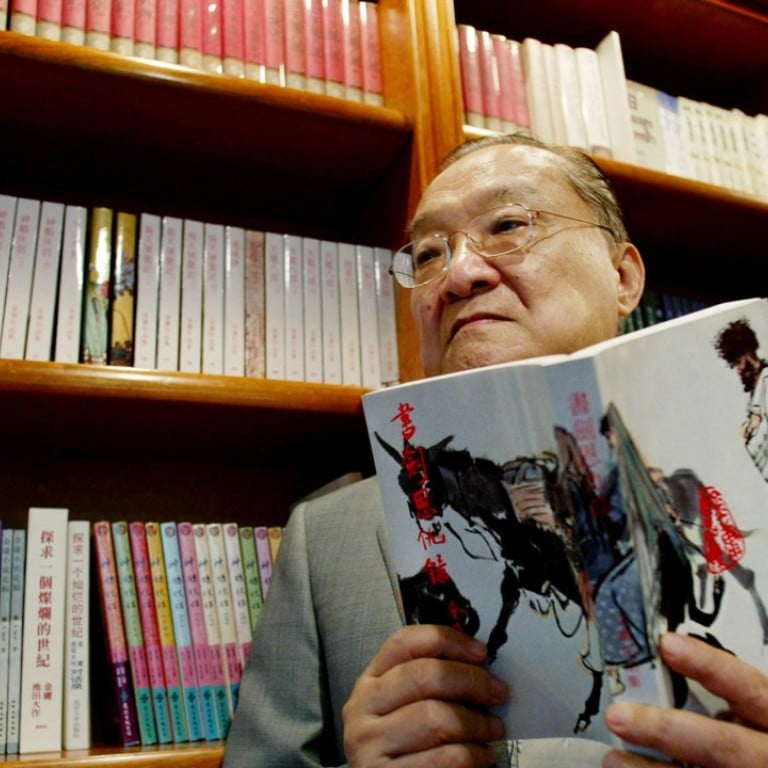

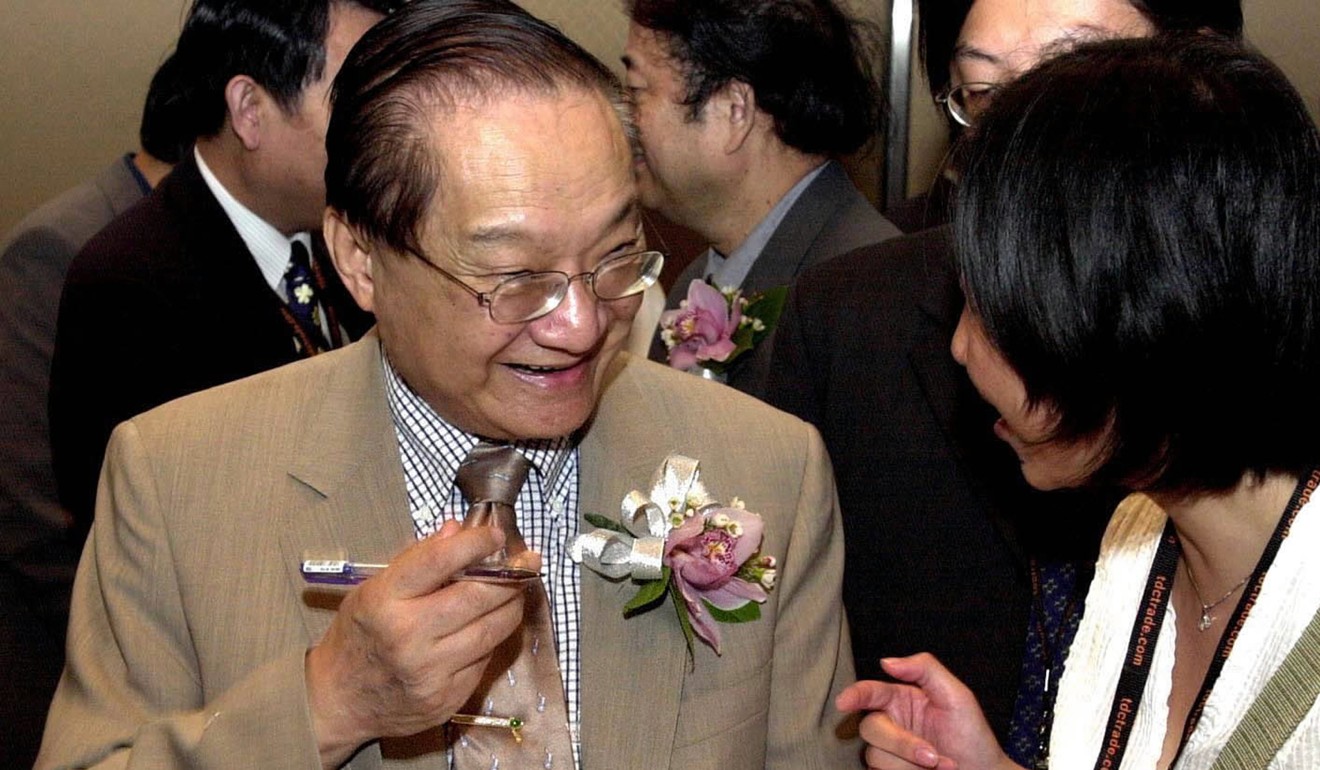

At lunch one day with Louis Cha Leung-yung, the late author of the kung fu novels that inspired pretty much the entire fantasy universe of China today, he told me about how he was not alone in hoping that his works could achieve some measure of international recognition, commensurate with their impact in the Chinese world.

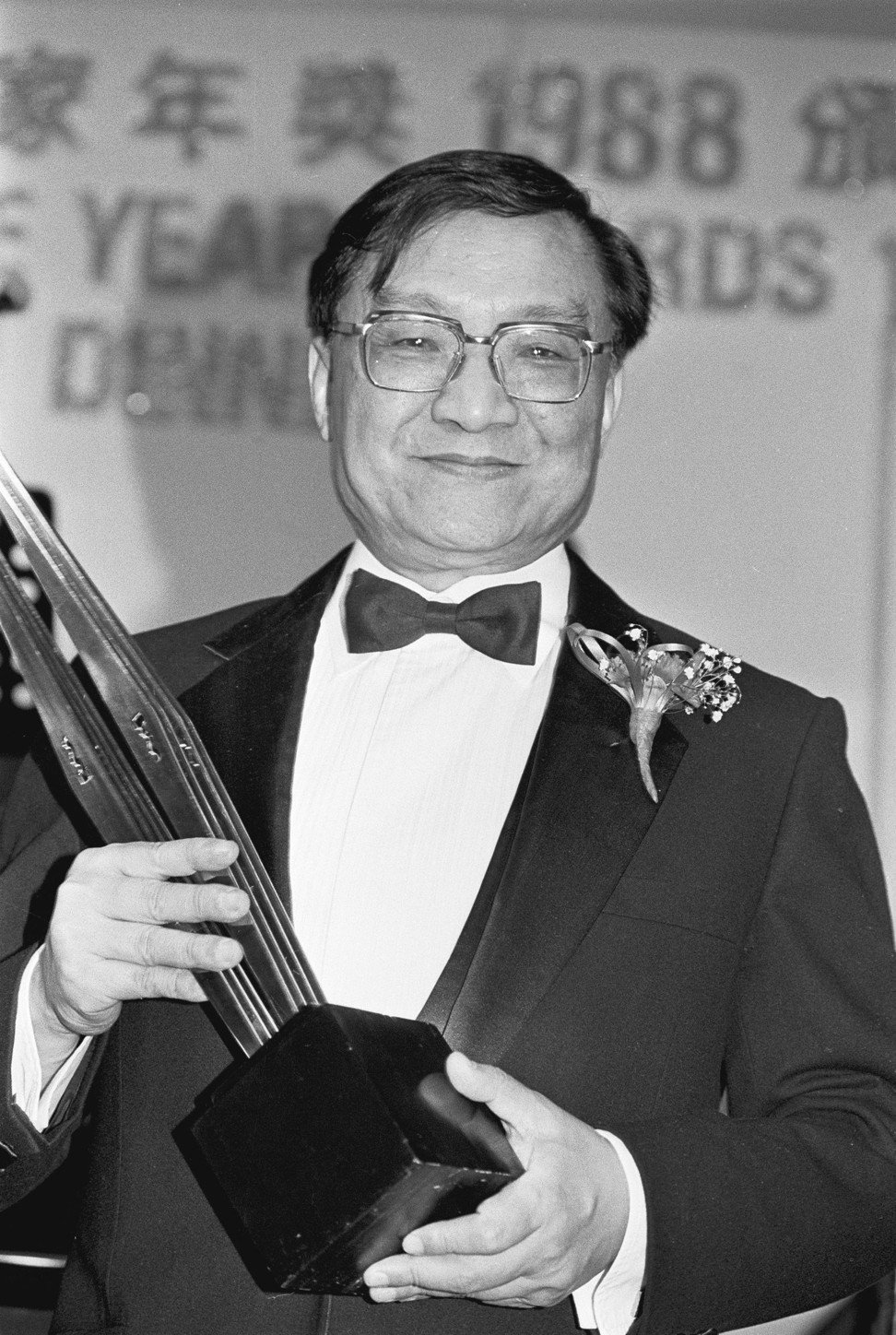

Former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin, Cha said, was a great fan. Jiang had arranged for an emissary to visit the Nobel Prize committee and say it was time for a Chinese writer to get the prize for literature, and that the Chinese government believed Jin Yong, Cha’s pen name, was the right writer to be honoured.

“Of course, they declined,” Cha said, as he told the story over lunch at a Western restaurant in Hong Kong’s Happy Valley area. “And the irony was that with the suggestion having been made, I was forever ruled out from being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.”

Cha was always eager to have his stories gain recognition globally, and in terms of their sheer cultural impact, there is no doubt he deserved that Nobel Prize.

When I contacted him in early 1979, to say that I was translating his book, The Book and the Sword, into English, he was very enthusiastic and generous with his time. He made himself available to answer questions, and I used the opportunity to speak with him regularly, often on the phone. We spoke almost exclusively in Cantonese, a foreign tongue for both of us, but his accent was far stronger than mine.

There had been only one translation of any his stories before I contacted him, and it was not well-regarded. I was busy doing many things at the time and it took me three or four years to finish it. I translated pretty much the whole thing, which, in the Hong Kong Chinese editions of the time, was two volumes and about 800 pages in total. I then put it to one side. It was about 15 years later that I was contacted – either by Cha or by Oxford University Press – about publishing it.

Cha and OUP had created a plan with the master translator John Minford, who had done a large part of The Story of the Stone – an English version of Dream of the Red Chamber. The plan was that John would translate the entire Jin Yong oeuvre for OUP, the only exception, at Cha’s insistence, being The Book and the Sword.

John did the first book to be published in the series, The Deer and the Cauldron, the last of Cha’s novels; mine was the second, published in 2004.

The rest were never done by OUP, for reasons I am not privy to.

Then came an edition of Legends of the Condor Heroes last year by another publishing house, MacLehose Press.

But all of Mr Cha’s books have been re-published in a number of Asian languages, including Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese, the mother tongues of countries that share many of the cultural underpinnings of China.

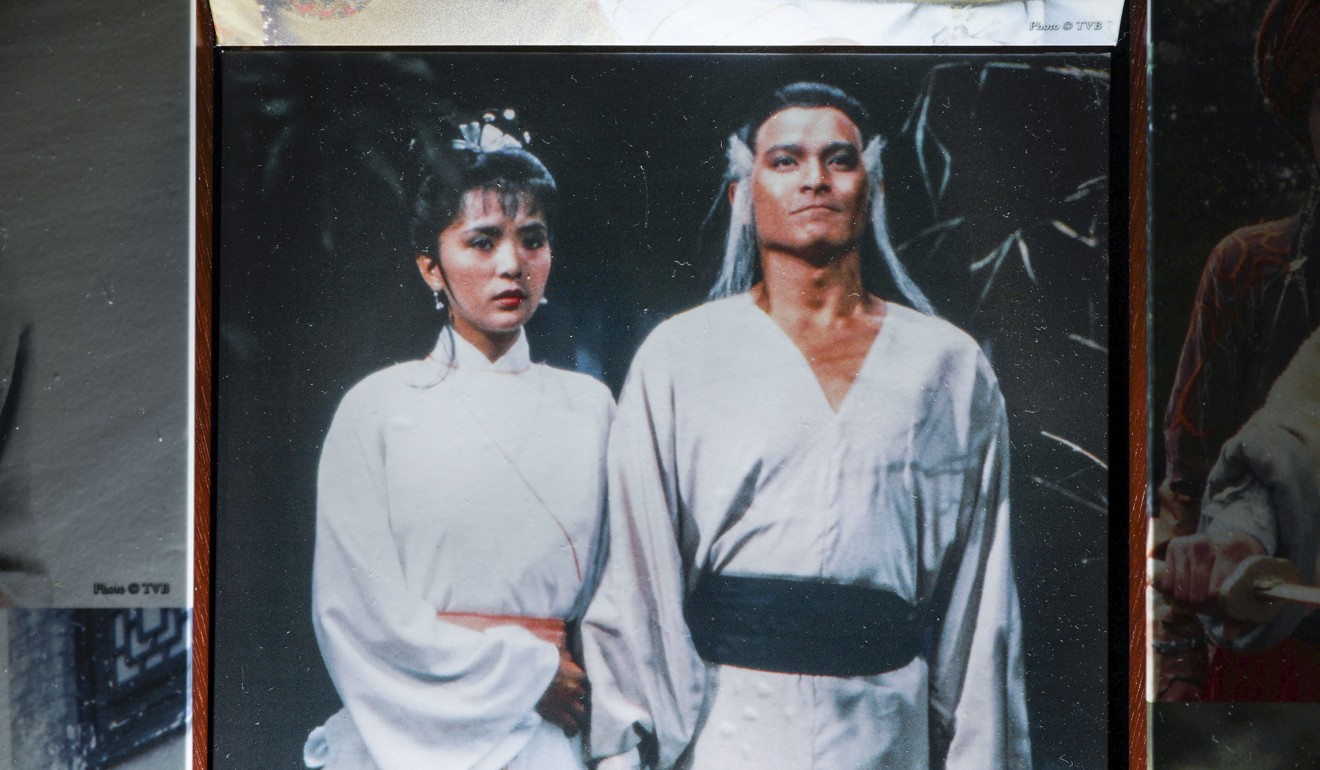

These works have all been filmed many times for television and the cinema. Many of the characters that Cha created have become a part of life for Chinese people, in much the way that Dickens’ Oliver Twist was a part of the lives of Victorian readers and the Harry Potter series is a part of our lives.

The Book and the Sword was the first novel Cha wrote. The story has a panoramic sweep which takes as its base a few unbeatable themes: secret societies, kung fu masters and the sensational rumour – so dear to Chinese hearts – that the great Manchu emperor Qianlong was in fact Chinese and not Manchu.

It mixes in the exotic flavours of central Asia, a lost city in the desert guarded by wolf packs and the Fragrant Princess. This lady is an embellishment of an historical figure, although whether she actually smelled of flowers, we will never know.

I am not a professional literary translator, and I learned Chinese on the streets. I started translating the book to help improve my Chinese, but after a while other ideas impinged on the process. Maybe it could be published in the West, I thought, and become a big success like Eric Van Lustbader’s The Ninja and James Clavell’s Shogun and a bunch of other popular novels of the era with intensely Asian themes.

It did not happen, although the OUP edition sells steadily in small numbers. The main reason, I think, is the style of the storytelling. Which is ironic, because in Chinese terms, Cha’s writing was a huge leap in the direction of Western literary methodology compared with his forebears.

Apart from the subject matter – often dramatic events from Chinese history that mean nothing elsewhere – the amount of description and the things described and not described, I think, make it difficult for Western readers to relate to Cha’s work.

Cha was writing for a Chinese reader who could visualise scenes and clothes and situations that would require significant explanation to be clear for a non-Chinese reader.

The rules of dialogue were also somewhat different and the story arc did not necessarily match what a Western reader would expect. Some of the fight scenes go on and on and on. Some culturally specific plot developments, which made sense in Chinese terms, wouldn’t necessarily make sense to those who did not grow up in the culture.

Cha was writing for a Chinese reader who could visualise scenes and clothes and situations that would require significant explanation to be clear for a non-Chinese reader.

I am thinking – why, I wonder? – of how The Book and the Sword’s hero, Chen Jialuo, spends an enormous amount of time alone with the Fragrant Princess in the desert and never makes a move on her.

So I decided that something had to change, and the rule I set for myself as I edited my draft translation was that I could cut, but not add. A couple of sub-plots disappeared and many of the fight scenes were cut back dramatically.

Cha was writing in those days to fill space in the newspaper and the more words he wrote, the more space he filled – just like Dickens. I once asked him about all the flowery names he gave to the kung fu fighting moves and weapons and whether they precisely described things he knew of. He said, no, he was largely just making it up to sound colourful. That was a relief for me.

So I tried to be as faithful to the spirit of the original as I could be, and simplified some elements of the story and the writing to make it more acceptable to an English-reading audience. I of course checked this with Cha and he agreed with my approach. As a result, there are some differences between the original and my translation, but they are differences only of omission. In other words, I have added nothing.

It was different with The Deer and the Cauldron. I cut and simplified, while John embellished and changed. There was once a discussion between John and myself at the Hong Kong Translation Society where I had been invited to speak on my translation of B&S. I have a recording of it.

Basically, John’s view was that the translator had a responsibility to enhance Cha’s work to make it acceptable for publication in English. I disagreed with this approach. The problem with it is that the reader cannot then know what is Cha and what is John Minford. With my approach, you can at least be sure that everything there is Cha.

The Chinese diaspora turned out to be the natural market for English versions of Cha’s books, at least in the short term. Hundreds of people have contacted me over the years since The Book and the Sword was published to ask when I would do another one, and, interestingly, almost all of them are people of Chinese ancestry living in places like Canada and Australia.

They understand the cultural context because of their family background, but they cannot read the Chinese books. So an English version is, for them, a godsend.

The problem of getting the works of Louis Cha across the cultural gulf and accepted in the Western world is not going to be solved any time soon. Yes, they are popular novels. But they are also deeply reflective of Chinese culture, with deep roots in Chinese history, language and nuance.

The integration of Chinese culture into world culture is very important, and it will happen eventually. When it does, Cha’s stories and characters will be an important part of it. It is just a shame it did not happen in his lifetime, as he deserved.

Graham Earnshaw, who worked with the South China Morning Post in the 1970s, translated Louis Cha’s The Book and the Sword