Chinese dealers who made Hong Kong an antiques trade hub recall the glory days

Antiques traders – including many Muslims – fleeing China’s political turmoil set up in Hong Kong in the 1940s and made fortunes; now changing tastes, high rents and competition from auctions are pushing them out of business

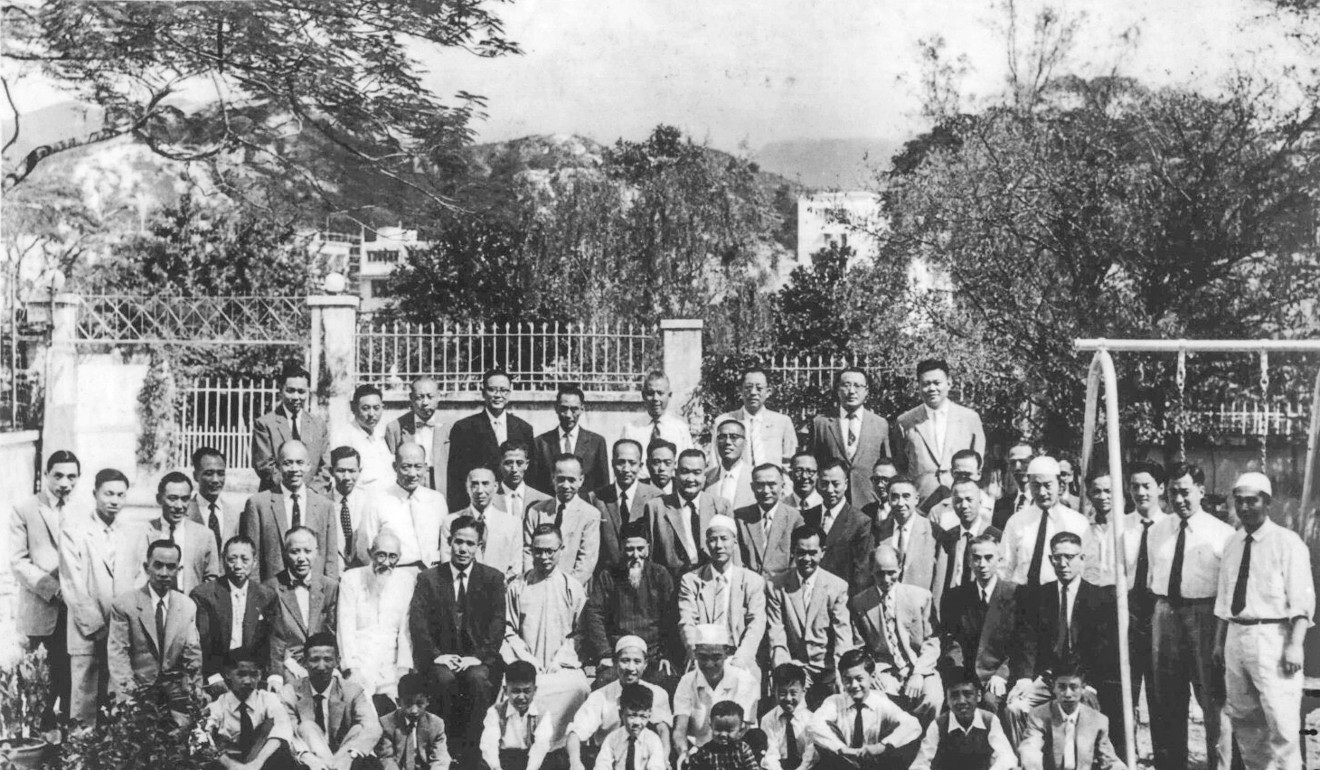

You can almost feel the warmth of the mellow autumnal sun bathing the five dozen men and boys as they pose for the camera outside 29 Kent Road, Kowloon Tong.

Two bearded elders in mandarin jackets are looking sombre, as befits the occasion, but the rest of the northern Chinese antiques traders appear relaxed, jolly even.

In their well-tailored suits, white shirts and ties, they might be enjoying a brief respite from work. Some have their sleeves rolled up, perhaps after the exertion of organising the group shot. Were it not for the few visible Islamic taqiyahs, or prayer caps, this would be like any other gathering of industrious, prosperous Hong Kong businessmen and their sons on that October 1957 day. Indeed, it seems more a show of force by a confident fraternity that had quickly found its feet in a new city than a scene of mourning in the garden of the deceased.

Even the toddler in the front row looks smug, sitting with his elbow jutting out, hand on chubby thigh.

Hei Honglu, now 84, took that photograph, with a brand new Rolleiflex camera. It was his boss who had died, a relative who had employed the young man in his antiques and curios shop when he arrived in Hong Kong as a 16-year-old, in 1949.

“We were Muslims from Beijing and it was a ceremony to mark the 40th day after my relative’s death. Men and women were segregated, so that’s why they were all males in the picture. Most of the northern Chinese dealers in Hong Kong came, and among them were quite a few Muslims,” recalls the genial trader in his Nathan Road office of more than 30 years. “It is a business that we have a long history in.”

Hei, who speaks Cantonese with a heavy Beijing accent, is still trading antiques, more than six decades after that photo was taken, albeit in a low-key manner, from inside an inconspicuous building just across from Kowloon Mosque, in Tsim Sha Tsui.

He shares his flat, which is on the same floor as his office, with his wife – Zhang Bing-wen, who is from another Beijing Muslim antiques trading family – a great deal of wooden furniture, centuries-old bridal chests, miscellaneous collectibles and volume upon volume on Chinese antiques.

He has lived and breathed antiques since his teens and brought up his son, Andy Hei Kao-chiang, to do the same. But these two men may well be the last of their breed – Muslim Chinese dealers who helped turn Hong Kong into one of the world’s biggest antiques markets.

Most fathers and sons in that 1957 picture have abandoned the business and other dealers who had traded for decades along Hollywood Road on Hong Kong Island have been wiped out by high rents and competition from auction houses.

Billions of dollars are flooding into the Hong Kong art and antiques market, but for the Heis the city is no longer the same land of opportunity that filled the Kowloon Tong party with such optimism.

Hei Snr still refers deferentially to his late relative as lo baan (boss), a Beijing dealer who left China just before 1949 with his son and a few portable antique pieces. They sold those, then restocked, and set up the Tung Cheng Peking Trading Company.

The business, which first operated on Hennessy Road, on Hong Kong Island later, in Hankow Road, in Kowloon, did extremely well. By 1954, Tung Cheng Peking Trading was an elected member of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, back when the powerful business group was dominated by established British traders.

Lo baan lived on the site of what is now the Yew Chung International Children’s House, in Kowloon Tong, by then already a neighbourhood for the wealthy.

The old clients have gone along with the generous housing allowances that expatriates used to get. Westerners also don’t have the same romantic idea about ‘the Orient’ that used to spur Europeans and Americans to study, collect and live with Chinese antiques

The period from the 1950s to the ’70s saw the beginning of Hong Kong’s economic miracle. The blow dealt to the city’s post-second-world-war recovery by the Korean conflict and the consequent American-led blockade on Chinese trade was ameliorated by an influx of people from China who brought fresh capital and built factories, reducing the city’s reliance on the entrepôt trade.

The antiques business flourished in this environment and the market was dominated by dealers from China who moved to Hong Kong to escape the political and economic turmoil after the Communist Party took over.

Hollywood Road as it is now didn’t exist. True, there were Cantonese dealers in the adjoining Upper Lascar Row (Cat Street) well before 1949. One of them was Luen Chai Curios Store, which now trades under the name K.Y. Fine Art under Ng Kai-yuen, who took over his father-in-law’s original business.

But the new arrivals from Beijing, Fujian and Shanghai set up shop all over town.

T.Y. King Antiques, owned by the Muslim King family, from Shanghai, had a shop in the old Alexandra House, Central. Robert Chang, who is in his 90s now and still trades through auction houses, was the son of a well-known dealer in Shanghai. He had a shop in Ocean Terminal, Tsim Sha Tsui, which was popular with antiques dealers because of the wealthy cruise-ship passengers and United States Marines who would pass through.

The Fujian and Beijing dealers were less flashy than the Shanghainese businesses and sold everything from antiques and jewellery to decorative accessories from premises around Hankow Road and Nathan Road, in Tsim Sha Tsui.

The field widened in the late 1960s, when Hong Kong began to attract more international collectors. Western dealers such as Hugh Moss and Glenn and Lucille Vessa, of Honeychurch Antiques, began to trade in the city. Hollywood Road started to fill with antiques shops catering to expatriates and visitors, initially from America and Europe, later from Japan and Taiwan. In 1973, Sotheby’s became the first international auction house to hold regular sales in Hong Kong.

Back in the early ’50s, Hei was doing the donkey work for lo baan.

“I worked and ate at the shop. I got only four hours of sleep every night. Sometimes I delivered furniture on foot. There were very few roads back then. I once carried an antique chair on to a walla-walla [a small boat] to cross the harbour and then walked all the way up to Mid-Levels, to an American expatriate’s home. We hired coolies to take the bigger pieces. There wasn’t GoGoVan then!”

Contrary to popular belief, Chinese traders made frequent trips “home” to restock.

“There was more freedom of movement than you’d think in the years immediately after 1949,” says Andy Hei. “It’s not as if people escaped like refugees. My father’s immediate family stayed in Beijing. All he had to do was to purchase an exit permit from a government office in Tiananmen Square and get on a boat in Tianjin.

The dealers in Hong Kong often returned to [China] and bought from the antiques market in Beijing’s Liulichang district or from dealers who kept stock at home.”

There were restrictions, though.

“Nothing as old as Han [206BC-AD220] and Tang [AD618-907] dynasty was allowed to be taken out but Qing [1644-1911] and Ming [1368-1644] stuff, no problem,” says Hei Snr. “Even imperial kiln ceramics could be exported.”

Hong Kong dealers continued to source from China during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.

“The government was desperate for foreign currency so, in the 1960s, it set up the China [National] Arts and Crafts Import & Export Corporation and sold antiques at regular export fairs in Guangzhou, Tianjin, Beijing and Shanghai,” says Hei Honglu.

That’s not to say he didn’t feel any trepidation in 1972, when he first returned to his old home in Beijing. At the time, the Red Guards were still hell-bent on destroying everything that was old and beautiful.

“I went back to see my mother for the first time since 1949. I know it seems odd today, but I just didn’t dare ask my relatives for a holiday until I quit their employment,” which he had done in 1970.

“I was told to blend in as much as possible. I wore liberation gear and swapped my gold-rimmed glasses for black plastic ones,” he remembers. Muslims felt particularly nervous about being targeted after Ma Lianliang, a legendary Peking opera star of that faith, had been persecuted and had his extensive antiques collection destroyed or stolen. Many local dealers had their stock confiscated and sold through the trade fairs.

“Nobody felt safe, but my family were left alone because they were totally proletariat,” says Hei. His father had been an illiterate Inner Mongolian shepherd who walked his flock all the way to market in Zhangjiakou, just north of Beijing. After the family settled in the capital, Hei went to primary school for just three years and was sent to work in a relative’s jade and jewellery shop. But it was in Hong Kong that he fully learned his trade.

Having quit his relative’s company, Hei set up a business that traded furniture and decorative pieces made of wood.

“I rented a small upstairs office in Chungking Mansions at first. There was no lift,” he says. “I used to have to slide the bigger pieces down the stairs.”

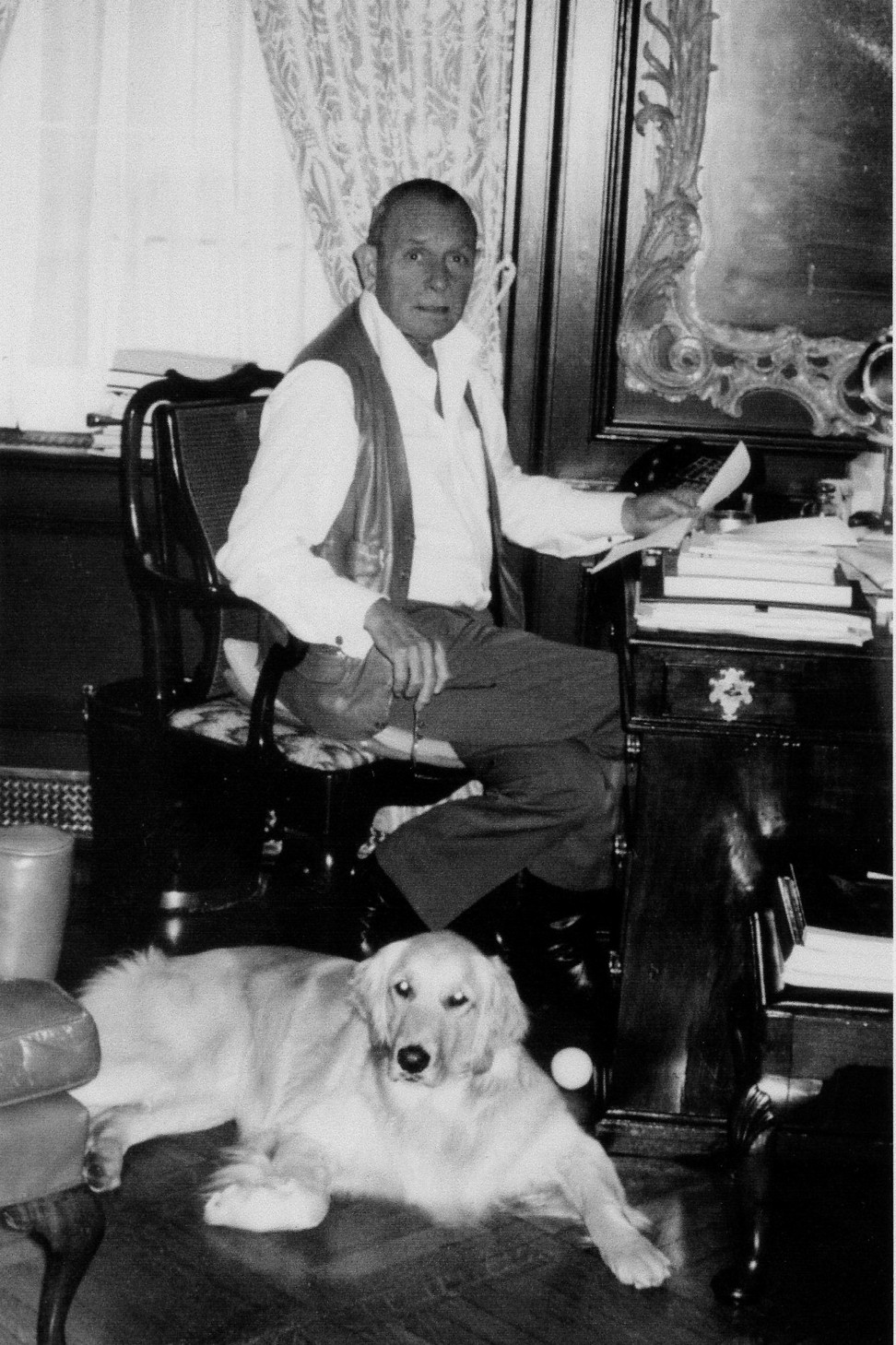

Hei relied on word of mouth. It also helped that he had a decades-long connection with American dealer Robert Ellsworth, who put together the collections of philanthropist John D. Rockefeller III and local businessman Joseph Hotung.

“Ellsworth first came to Hong Kong in 1949 on the American President Lines via San Francisco, Honolulu and Yokohama. This 19-year-old lad showed up in my relative’s shop in Hankow Road and bought a few pieces of imperial kiln ceramics.

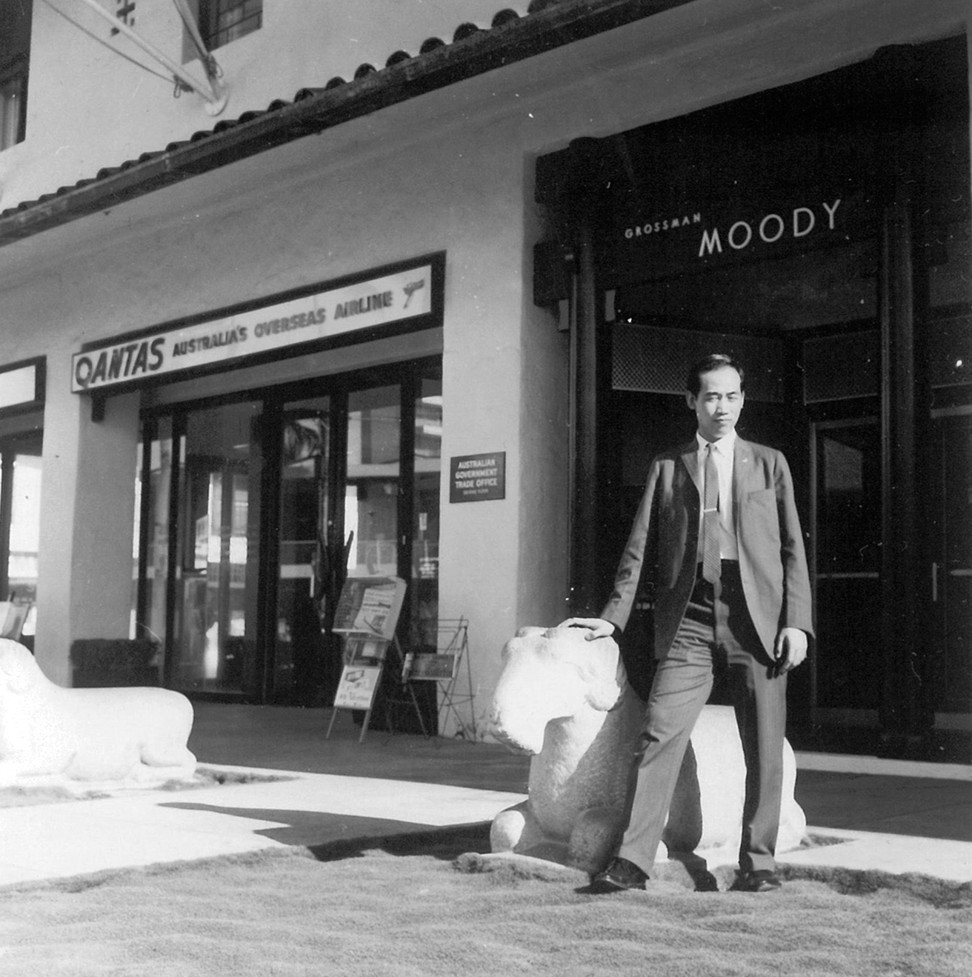

“They were relatively cheap then and he was very clever, trading things with the little money that he had and making a profit. He opened his own shop in New York in the 1950s. In 1962, I went to America for the first time and looked him up. That’s when we started to collaborate,” says Hei.

In the late ’70s, Ellsworth began work on his three-volume Later Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: 1800-1950, an exhaustive survey on the subject. He asked Hei to accompany him to China.

“I loved this simple painting of a catfish. Ellsworth didn’t want it because he already had a lot of Qi Baishis, so I bought it for US$4,000,” says Hei. The painting hangs in his office. The fabulously resilient fish was a favourite symbol of longevity for the modern Chinese painter.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Ellsworth aggressively bought ancient artefacts taken by raiders from tombs in China and smuggled out of the country – a trade prompted by desperate poverty in a newly opened economy, lax customs checks and widespread corruption. It was the beginning of the golden age of antiques trading in Hong Kong.

“Ellsworth decided to keep an apartment in Kowloon then and spent all his time in Hong Kong checking all the shops for stock,” says Andy Hei. “The Taiwanese and Japanese were also buying then but it was the Americans who dominated the market.

“Fortunately for antiques dealers, they didn’t have any sensitivity against burial items. Chinese people wouldn’t buy those Tang-dynasty terracotta figures dug out of graves but, because Westerners wanted them, Hollywood Road was full of them.”

Hei Honglu was himself an intrepid hunter of what he calls bo, “treasure” in Cantonese. In 1970, he discovered bo in a gallery in Honolulu, Hawaii.

“I was so excited I couldn’t sleep that night. I bought it the next morning,” Hei says. “It was a big piece of white jade in the shape of a mountain that had belonged to the Qianlong Emperor [reigned 1735-1796]. I didn’t have enough money but they let me pay in instalments. I carried this 15, 16-pound stone with me to San Francisco, New York and back to Hong Kong. I sold it to my father-in-law, also a dealer.

“Later, someone who had it in his possession told me that he had looked into its provenance and found out it had been stolen from the Palace Museum.”

Today, the eagerness of wealthy Chinese collectors to retrieve sold or stolen national treasures is linked with the nation’s determination “to be great again”; and that is no bad thing for the dealers who handle them. Prices have soared.

Nevertheless, the mood is gloomy along Hollywood Road, where Andy Hei has had his own furniture shop since 2000. Last summer, Honeychurch Antiques became the latest of many dealerships to close their doors for good. Rising rent is the main cause. In the ’80s, the average monthly rent was HK$10,000. By 2000, Andy Hei was paying about HK$30,000. And then the market went berserk.

“At its peak, a 1,000 sq ft [street-level] shop [west of Aberdeen Street] was let for HK$200,000 a month,” he says. “It has come down a bit but I am still paying several times more than I did in 2000.”

In some ways, the industry has also become a victim of its own success. “It is hard for anyone to set up a new business unless they come from a family of dealers with an existing inventory. It costs so much to buy now, and there are so many fakes out there,” Andy Hei says.

The market has changed dramatically in other ways.

“The old clients have gone along with the generous housing allowances that expatriates used to get,” he says. “Westerners also don’t have the same romantic idea about ‘the Orient’ that used to spur Europeans and Americans to study, collect and live with Chinese antiques. Buyers [from China] have different tastes and ways of doing business.

“They bargain. They are impatient. They phone you up at midnight on a Sunday.”

Andy Hei survives on new business models. WeChat allows better communication with his clients from China and he has diversified into art fairs. In 2006, he launched Fine Art Asia, an international art and antiques fair that has expanded into contemporary art fairs in Hong Kong and Beijing.

“I still make most of my income from my furniture business, but the art-fair business is growing and it helps me meet potential clients. It’s a tough business to be in, though. I’ve opened up crates to thousands of cockroaches and rats. It’s really not for everyone.

“I am not going to tell my 10- and 12-year-old son and daughter to follow in our footsteps.” ■