Shenzhen’s growth is poised for another leap into warp speed as the Greater Bay Area kicks off

It seems that Beijing’s plan to create the Greater Bay Area in Guangdong province is arriving not a moment too soon.

Not only is it one of the biggest new economic ideas to erupt in China since Deng Xiaoping seeded the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) across southern China in the early 1980s, it is going to be big for Hong Kong. But that is not today’s story, for above all else, it will be big for Shenzhen.

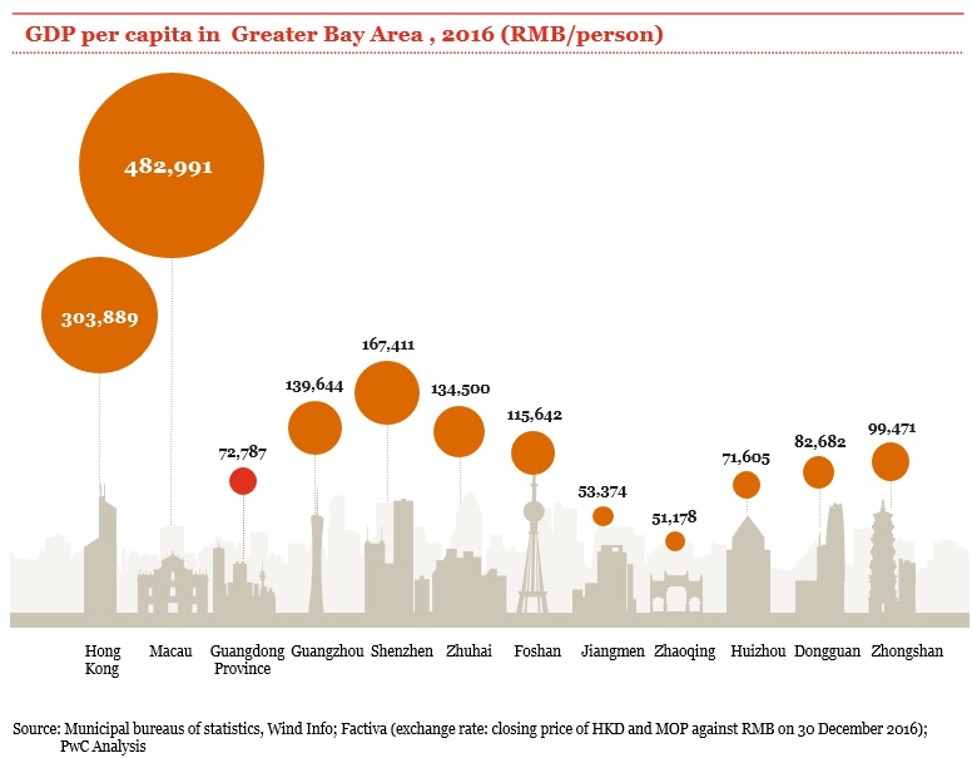

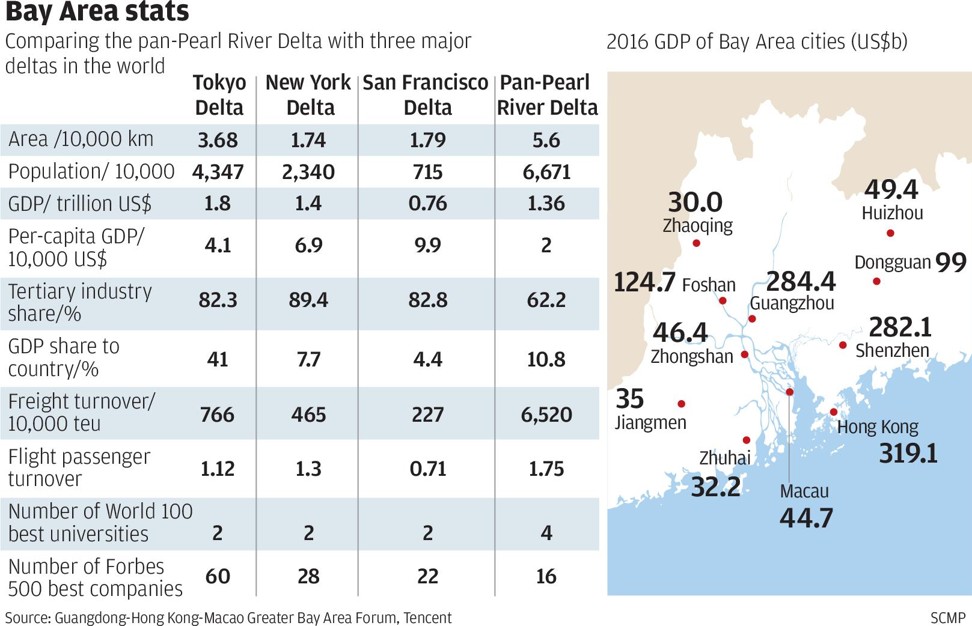

Shenzhen’s extraordinary 21st Century growth story is unique. It has in some ways outgrown Hong Kong. But it has also outgrown itself. It is the perfect locus for southern China’s next big leap - to sit at the heart of the creation of a globally significant megacity region that will perhaps embrace 65 million people.

But it is open to question whether it has the coherence and institutional maturity to fulfil what otherwise might be its destiny. If we in Hong Kong are smart, we will work jointly with Shenzhen to build a shared destiny. Who knows whether that will happen.

There is a dreamlike unreality in comparing today’s Shenzhen with the ramshackle township I first saw in the late 1970s.

There was little to attract notice. Shenzhen may not quite have been the fishing village of urban mythology - local accounts say the hamlets and towns of Bao’an County amounted to around 58,000 people - but it was hardly going to stir the adrenaline of the occasional sleepy visitor.

In my first glimpse - through British army binoculars across the Shenzhen river - it was hard to spot the occasional wooden houses dotted along the shoreline and even more difficult to forget the bedraggled bodies of young Chinese men who had died overnight trying to swim across the river.

When I first ventured across into Shenzhen, the most notable features were bucolic traditional Chinese villages clustered around fish ponds, fields of sugar cane, and water buffalo hauling ploughs through rice paddies. I was taken to a single factory, a bus-building plant. Workers were beating bus panels by hand. It made six buses a year.

Stand today in the bustling shopping streets of Luohu (Lo Wu) or surrounded by the luxury high-rises of Futian and Nanshan, and it is impossible to imagine such an astonishing transformation in less than four decades.

People talk of “Shenzhen Speed” with good reason, a city of 12 million permanent residents and an economy on a par with Hong Kong, Singapore and Guangzhou.

None of this would have happened without the pragmatic vision and charismatic force of Deng Xiaoping and his 1978 decision to open the country up and let some foreign flies into newly agreed Special Economic Zones.

By the time Deng made his first visit to Shenzhen in 1984, the SEZ was already moving at warp speed towards the city we see today, though those of us outside China, still dazzled by the bright lights of Hong Kong, would take almost two decades to take proper notice.

That was not so for Hong Kong manufacturers who, squeezed for space and struggling with high labour costs for their cheap plastics, toys, garments and shoes, saw Deng’s opening doors as perfectly timed. Hong Kong and Taiwan manufacturers flooded into Shenzhen and neighbouring Dongguan by the thousands.

Within a decade, they were employing more than 10 million workers, most of them barely-skilled immigrants from the Chinese interior. They flattened hundreds of traditional villages, and consumed the region’s rich farming land, but transformed a neglected backwater region into China’s biggest exporting region, and by far the biggest magnet for international investment.

By the middle 1990s, the comparative openness of the Shenzhen economy, its export orientation, and its proximity to Hong Kong’s international connections and financial markets, began to attract a new generation of highly driven mainland entrepreneurs. At some point around the turn of the century, these became the dominant drivers of growth in the Shenzhen economy, most of them working in hi-tech areas.

Today, hi-tech accounts for around 65 per cent of the Shenzhen economy, as the early industrial founders - low tech, low value-adding, and horribly polluting - declined, being quietly airbrushed away by political leaders keen to credit Shenzhen’s growth to the mainland’s own entrepreneurial spirits.

Tech leaders like Huawei Technology, DJI and Tencent Holdings are what distinguish Shenzhen today.

Growth at Shenzhen’s breakneck pace could not possibly come without a price. Stop someone on a street corner in Futian district and the betting odds are that the person is in their mid-20s, is a recent immigrant, and is “in trade, or technology”.

This creates some awkward city demographics that will be difficult to resolve: take any other city of 10 million anywhere in the world, and you will quickly be aware of centuries of history, and of historic buildings often nested around the metropolitan heart of the city.

You will see strong civic institutions, and people who have proudly regarded themselves as “local” for generations, contributing to the community, its arts, its culture, its politics.

But Shenzhen’s roots are shallow in the extreme. Today’s business and community leaders are just beginning to throw down such roots and working to develop a sense of “localness”.

At this stage, it is perhaps not an accident that Shenzhen’s city bird is the black-faced spoonbill - a migrant - and its most famous sightseeing spot is “Window of the World”, a theme park collection of miniature copies of some of the world’s most iconic buildings and landmarks.

A final clear challenge for a dynamic upstart like Shenzhen is the potential for rivalrous sidewards glances from cities that have through recent history always regarded Shenzhen as insignificant - at best a little brother. And this is where Beijing’s timely promotion of the Greater Bay Area has such significance.

What the Greater Bay Area will become is as yet unclear, but its potential, and Beijing’s vision for the future of southern China, are awesome. In place of counterproductive rivalries, there is the opportunity for each component part of the Pearl River Delta to play to its strengths, and to work closely with other parts of the region to counterbalance weaknesses.

That applies as much to Hong Kong and Guangzhou as it does to Shenzhen - but as the dynamic upstart of the region, it is the opportunities for Shenzhen that gleam out most clearly.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view