Shenzhen set to have world's first all-electric public bus fleet

Massive subsidies helped catalyse the shift from diesel in the pollution-choked southern Chinese city

A cloud of diesel fumes envelops us as a bus pulls away from a stop on Dongzong Road, in Shenzhen’s Pingshan district. Nothing unusual about that, you may think – we are in one of the most polluted countries in the world, after all – but we are unlucky enough to be standing behind one of very few buses in the city that still run on diesel.

More than 14,000 electric buses ply the roads of Shenzhen and the several hundred remaining diesels are due to be phased out by the end of 2017. This puts Shenzhen ahead of not only Beijing, Hangzhou and Nanjing, but also Paris, Oslo and London, and will earn the city the distinction of becoming the first in the world to have an all-electric public bus fleet.

Although China is not alone in embracing electric vehicles in pursuit of a cleaner urban environment – France and Britain will end sales of petrol and diesel cars from 2040 and Norway has set its target at 2025 – the country’s need is seen as all the more urgent because it has the world’s deadliest air pollution, according to the World Health Organisation, and is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Vehicles in China emitted 44.7 million tonnes of pollutants in 2016, according to the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and going electric is seen as a fix. The power needed to drive an electric vehicle must still be generated, of course, but one major advantage of moving pollution from the exhaust pipe to the power plant is that it takes pollutants farther away from the general population, lowering the adverse health effects. Concentrated emissions are also easier to manage.

BYD – the letters stand for “build your dreams” – manufactured 80 per cent of the electric buses in use in Shenzhen, the remainder having been built by other Chinese companies. On the streets of Pingshan, the suburb where BYD is headquartered, the bikes and cycle rickshaws running alongside the company’s gleaming electric buses make for a curious sight. Once aboard, a conductor takes our coins and hands us paper tickets, which only adds to the feeling of temporal dislocation.

BYD was one of the first manufacturers to propose all-electric bus fleets for China, in 2010. Having produced batteries since 1995, the company had, in 2003, branched out into new-energy vehicles (NEVs), a term Beijing uses to describe plug-in electric vehicles (battery only and hybrids).

“It was a bumpy ride in the early days as the technology was met with scepticism,” recalls Xiao Haiping, director of the BYD commercial vehicle sales division’s public relations department, speaking in his office within the Pingshan complex. The 1.8 million sq ft compound also contains laboratories, factories and employee dormitories.

BYD’s first electric bus, which was trialled in 2011, had four shelves holding large batteries, leaving little room for passengers. Other shortcomings included limited range and low speed.

A turning point came in 2014, when the authorities issued a list of policies to support the development of NEVs. In “Made In China 2025”, a 2015 plan to revamp the country’s manufacturing sector, NEVs were identified as one of 10 key sectors the government would throw its weight behind.

By last year, BYD had surpassed Tesla as the world’s largest maker of electric vehicles, exporting to more than 50 countries and 200 cities.

In Hong Kong, Kowloon Motor Bus was experimenting with electric vehicles as long ago as 2010, but neither the operator nor the government has yet taken decisive steps towards establishing a significant electric fleet. By contrast, in late 2015, Shenzhen Communist Party chief Ma Xingrui gave his city’s three operators – Shenzhen Bus Group (SBG), Shenzhen Eastern Bus Company and Shenzhen Western Bus Company – a deadline: three years in which to establish all-electric fleets.

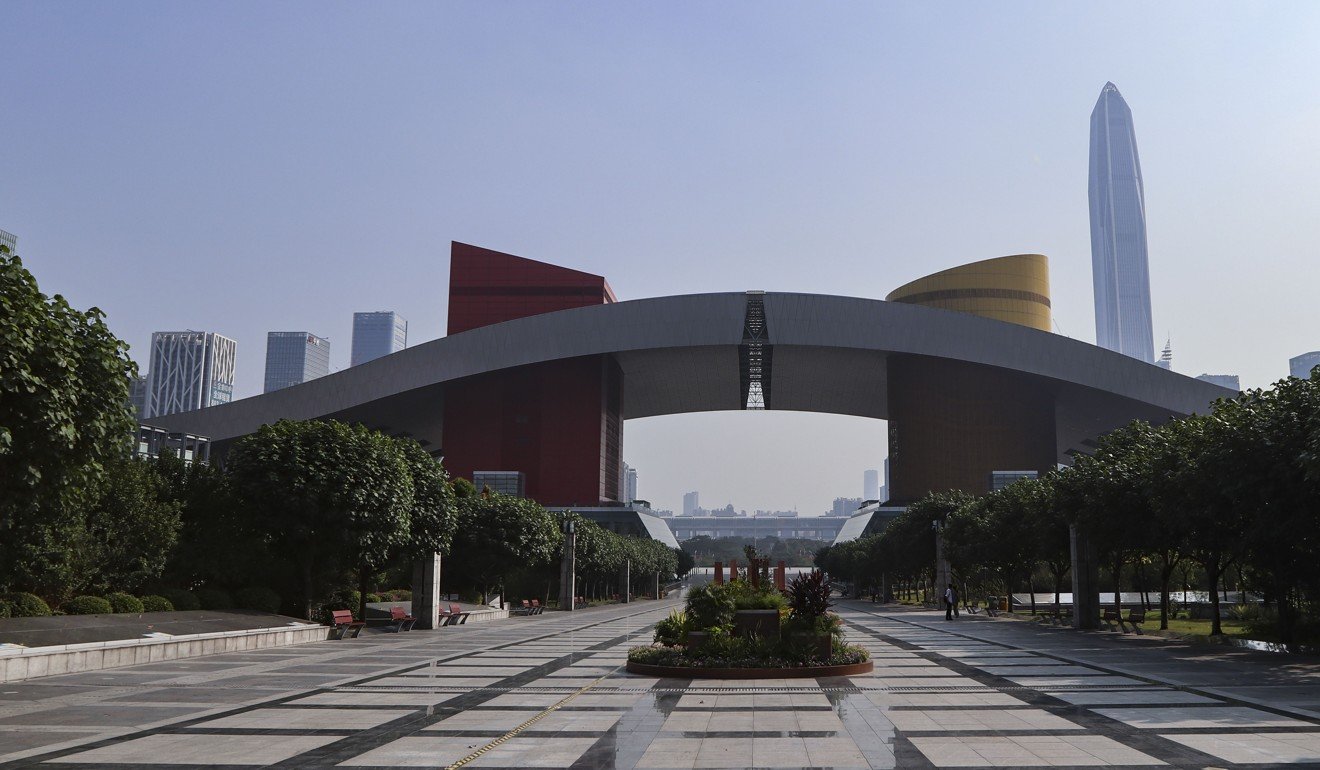

“The decision was a source of both pressure and motivation,” says SBG’s executive vice-director Ji Chilong in his office on the 21st floor of its Futian headquarters. Among the titles on his shelves are several copies of a book interpreting ancient philosophical wisdom, authored by Ji himself. “Part of our fleet at the time was poorly maintained and could not be replaced because we lacked the funds. [The push for an electric fleet and the subsequent subsidies] presented an opportunity for us to renew our entire fleet of 5,300 buses.”

SBG completed the switch in June, beating the deadline by more than a year. Scrapping diesel buses, the operator estimates, will have cut exhaust-pipe carbon dioxide emissions by 400,000 tonnes per year and other pollutants, such as carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide, by 2,000 tonnes.

As the technology matures, most of the performance shortcomings seen in earlier models of electric buses have been overcome, yet two problems remain: the vehicles are expensive and they require an extensive network of charging stations.

Funding is less of an issue for the second largest economy in the world than it is for other countries. And, as well as investing billions in research and development, the mainland authorities have backed the electric roll-out with generous subsidies, beginning with the batteries, which can account for up to 40 per cent of the production costs of an electric vehicle.

Even after that, SBG estimates, an electric bus would cost 1.8 million yuan (HK$2.1 million) – compared with 500,000 yuan for a diesel version – if the Shenzhen and central governments hadn’t agreed to each give a subsidy of 500,000 yuan per vehicle. And SBG negotiated a deal that allows it to pay its share for the buses in instalments, over eight years, so the company does not have to fork out 4.56 billion yuan (it now operates 5,698 electric buses) in one go.

Another benefit of electric buses is that they are cheaper to maintain than diesel vehicles, and operators are given a subsidy of 420,000 yuan per 12-metre bus to help cover operating costs.

Charging infrastructure is a speed bump working against the introduction of electric buses in many cities, including Beijing, but the Shenzhen authorities once again opened the coffers, offering lavish grants to attract solution providers. According to some reports, the city already has as many as 277 charging stations and more than 28,000 charging piles (of various speeds), of which SBG rents 82 and 1,341, respectively, for its own use.

With the government providing the financial muscle, manufacturers and operators have used their imagination to promote electric buses. When questions were raised about passengers’ exposure to the batteries, BYD invited media to one of its laboratories, armed them with detectors and had them see for themselves that the electromagnetic radiation given off was within safety levels. Shenzhen Eastern Bus Company dressed 10 couples working for the operator in wedding dresses and tuxedos, and paraded them around the city on electric buses. “Mass wedding on electric buses, most romantic in history,” read the banner hanging on each vehicle. (One assumes something is lost in translation.)

Another benefit put forward by advocates is that electric buses are much quieter than those they are replacing. It is indeed possible to tell the types apart with our eyes closed while standing at the Dongzong Road bus stop – gone are not just the noxious fumes but also the distinctive clatter produced by an ageing diesel engine. But a staff member at BYD’s acoustics test laboratory – a large room lined with blue and silver foam in which the utter silence makes the uninitiated feel uneasy and claustrophobic – reveals that there is no more than a two decibel difference between the noise of a new electric engine and that of a new diesel one. “It’s not a difference you can tell by ear,” she says.

The decision was a source of both pressure and motivation

Being closest to the finish line in the race for an all-electric bus fleet, Shenzhen hopes its success can provide lessons for other cities. But can the model be easily replicated?

For a start, it remains to be seen whether the generous grants will be sustainable.

Last year, Beijing conducted a nationwide investigation into NEV subsidy practices and five car manufacturers were punished for having defrauded the government of a total of one billion yuan. Subsidies on consumer electric cars have since been reduced, and sales have slumped. What would happen if something similar befell those involved in building and operating Shenzhen’s electric buses?

Undeterred, the city is considering its next challenge: an all-electric taxi fleet. Shenzhen has set 2020 as its goal, as has Beijing.

And so that race begins …

Electrobus investors taken for a ride

By Mike Hamer

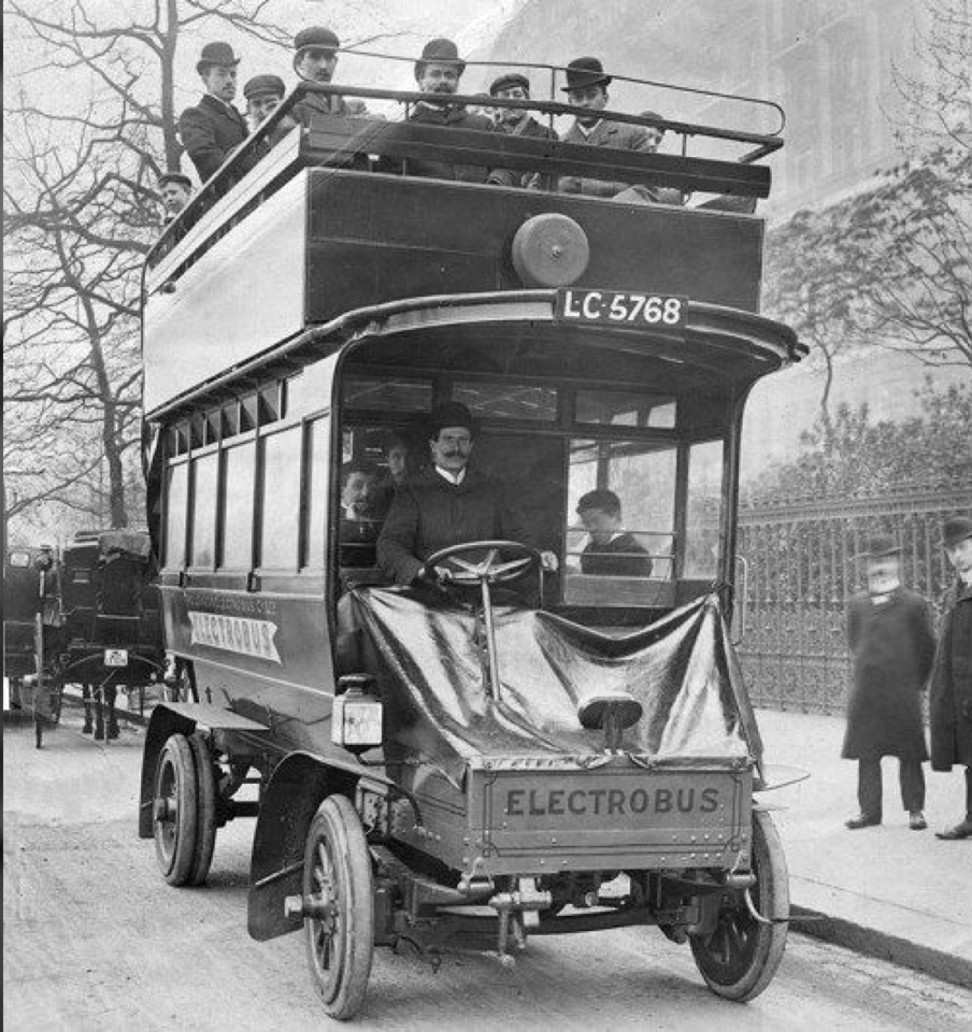

In the first decade of the 20th century, transport reached a tipping point. Would the future belong to petrol, electricity or even steam? The stage was set for a decisive showdown when the world’s first practical electric buses hit the streets of London in July 1907. They were clean, quiet, reliable and fume-free, unlike their petrol-powered counterparts, which were widely reviled for their deafening din and evil smells.

Electrobuses, as they were called, were an immediate hit with the British capital’s commuters, and the prospect of a successful challenge to the internal combustion engine was greeted with delight by press and public alike.

“The doom of the petrol-driven omnibus is at hand,” forecast the Daily News.

“The electrobus is probably a more formidable rival than the petrol omnibus, not only to the horse omnibus but also to the tramway,” concluded Douglas Fox, the country’s foremost engineer and designer of many of the world’s railways, at the September 1908 meeting of what’s now the British Science Association.

The future of electric vehicles seemed assured. The bus, with its fixed routes and hence predictable demands on batteries, seemed a promising application. If battery power proved its worth here, then other uses would surely take off. And London, the world’s largest city and centre of the British Empire, had a track record of setting global trends in technology, so there would be ripples around the world. Yet, in little more than two years, the electrobus was abandoned in favour of the combustion engine – and we are still suffering the consequences. What went so badly wrong?

At the start of 1905, there were a handful of petrol-powered buses in London. By 1907, there were almost 1,000 – more than in Berlin, New York and Paris put together. Horses still pulled most buses, but petrol had stolen a march on battery power. However, there were problems from the start.

Protests about noise and fumes had increased sharply with the surge in motor vehicles. Buses were not the only culprits, but because of their set routes and vivid eye-catching liveries, they were the focus for much of the ire. Newspapers were full of angry letters from the great and the good. One came from a friend of the late Queen Victoria, who wrote to The Times newspaper complaining of “the incessant roar and rattle and pestilential atmosphere and dust diffused by these monstrous vehicles”. A protest meeting held at the Medical Society of London was told that motor buses “ought to run underground in main drains, like other nuisances”.

The doom of the petrol-driven omnibus is at hand

During 1907, the police stopped petrol buses 8,500 times because of their appalling noise or noxious fumes. The average London bus was ordered off the road every six weeks. On top of this, they were extremely unreliable. At any time, at least a quarter were out of action. Broken-down buses littered the streets.

The electrobus couldn’t have appeared at a better time. Within days of its debut, one of London’s largest petrol bus companies went bust. In the summer of 1907, more than 100 petrol buses were scrapped. Horse-powered vehicles were making a comeback; despite being slower, they were cheaper and far more likely to reach their destination. The industry was in disarray and even supporters of petrol power conceded failure, at least temporarily.

Yet the marvellously clean, green electrobus failed to cash in. The history books generally put this down to its undeniably heavy lead-acid batteries. In fact, the technology worked rather well. The real reason it failed was that a gang of swindlers had a stranglehold on the companies that made and ran it. To them the electrobus was not a vehicle for change, it was a vehicle for fraud.

The originator of the swindle was Edward Ernest Lehwess, an enthusiastic motorist and sometime second-hand car salesman with a doctorate in law from the University of Zurich, Switzerland. Lehwess was an engaging cosmopolitan character, fluent in English, French and German, and with a taste for the good life. He was soon joined by Edward “Teddy” Beall, a flamboyant former solicitor who had been the brains behind more than 200 share swindles. Beall had only recently been released from prison after serving a four-year sentence for bank fraud. Given their unsavoury reputations, both men went to great pains to avoid having their names linked with the new enterprise. Beall, in particular, used dozens of aliases.

It was a con from the start. In the spring of 1906, the London Electrobus Company announced plans to put 300 electrobuses on the streets of the capital. It offered the public the chance to buy shares worth £300,000 to finance the project, claiming that it had acquired a patent for the huge sum of £20,000 that gave it a monopoly on the electrobus. This seemingly guaranteed that investors would reap enormous profits, and the public rushed to invest.

Almost immediately, however, inquisitive reporters exposed the scam. One bought a copy of the patent. He discovered that it was for a motor vehicle transmission – about as relevant to the electrobus as a patent for a hair dryer. Another reporter visited the west London works where the electrobuses were to be built. Instead of finding a production line gearing up to churn out hundreds of vehicles, he found a former stables next to a pub. Alerted by articles in the papers, angry shareholders demanded their money back. It all ended up in court and the electrobus company was forced to refund more than 1,000 investors.

Despite this initial setback, Lehwess wasn’t deterred. People’s enthusiasm for clean buses, and their willingness to support them with hard cash, convinced him that he had a sure-fire way of making a lot of money. But first he had to put some buses on the road, and to do that he needed reliable batteries. So Lehwess set sail for New York to meet Charles Gould, head of the Gould Storage Battery Company, based near Buffalo.

Through a series of meetings in the autumn of 1906, Lehwess convinced Gould to ship batteries and a team of engineers to London. Each battery weighed about 1.75 tonnes and could power a bus for just 60km. Recharging took almost eight hours, meaning vehicles would be off the road for half of their working day. But Gould’s engineers helped devise an innovative way round this problem. The batteries were bolted to the bottom of the bus. After the morning shift, buses returned to the charging station, where workers unbolted the batteries, lowered them with a hydraulic lift and took them off to be recharged, replacing them with fresh ones. This lightning pit stop took just three minutes.

So Lehwess had his batteries and, true to form, he failed to pay what he had promised for them. It would take Gould two years to realise that he, too, had been conned. Meanwhile, after months of rigorous testing, an electrobus picked up its first fares.

The inaugural journey began at Victoria Station at 7.30am on Monday, July 15, 1907, and headed off on a 6km route across the centre of London to Liverpool Street Station. With a fleet of six buses on the road, Lehwess and Beall were now ready to take investors for another ride. Beall was a past master at conjuring money from his suckers lists, with seductive circulars promising quick riches. According to one, the return on electrobus shares “should amount to about £26 per annum on the outlay of each £100”. There was no shortage of people with spare cash who were taken in. Between 1907 and 1909, the swindlers banked close to £95,000 – worth about £10 million (HK$102 million) today. Each time they raised more money, they promised to put dozens more electrobuses on the streets, but the number increased only slowly, reaching a maximum of 20 or so. Of all the money that had been poured into the electrobus enterprise, just £14,000 was spent on buying buses – and even that was paid to a company controlled by Lehwess, who, naturally enough, was grossly overcharging for them.

The end came on Monday, January 3, 1910. Loyal commuters turned up at Victoria Station as usual to catch their smooth, quiet, fume-free ride, but their electrobuses didn’t arrive. One final scam, a company “reconstruction”, had led to its demise. It was the end of the line for London’s electrobuses.

It wasn’t quite the end of the road for battery power – electric delivery vehicles lingered throughout the 20th century and electrobuses went on running in Brighton, southern England, for another seven years – but it was a decisive setback. The electric vehicle had lost what was probably its best chance of challenging the internal combustion engine.

The swindle didn’t just rob Edwardian investors of their nest eggs, it bequeathed a toxic legacy to the world’s cities. Today, diesel has widely replaced petrol as the most common fuel for combustion engines. In London alone, nearly 9,500 people a year die prematurely from breathing nitrogen oxides and ultra-fine particles known as PM2.5, mostly from diesel exhausts.

We are finally facing up to the problem. In 2009, the world’s leading industrialised countries agreed to promote electric vehicles with the twin aims of cutting air pollution and reducing carbon emissions. As a result, battery development is racing ahead. Most modern electric vehicles use lightweight lithium-ion batteries, and the amount of energy they can store has more than doubled in the past six years, while their cost has fallen by two-thirds. Demand for electric cars is soaring. They are still far outnumbered by diesel and petrol models, but perhaps not for long.

In July, Volvo, the Swedish manufacturer owned by China’s Geely Holding Group, promised to end the production of cars powered solely by an internal combustion engine within two years. Before the month was out, the governments of France and Britain had joined Norway in pledging to end the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2040 or earlier.

The electric bus is also making a comeback. There are now about 350,000 worldwide, many of them in China (see main story).

The future of transport has reached another tipping point. But imagine how things might have been if we had not missed the opportunity to embrace battery power a century ago. New Scientist

Mick Hamer’s book A Most Deliberate Swindle is published by RedDoor.