A slow and bumpy ride ahead for China’s economy amid mounting debt and the end of cheap funds

Analysts warn that policymakers who meet for the annual Central Economic Work Conference will have to be cautious with their economic policies

When bank governors of 10 of China’s biggest banks gathered in a hotel in West Shanghai’s Hongkou district on November 30 to protest against draft rules issued by regulators to consolidate the country’s 100 trillion yuan (US$15 trillion) financial services industry under a single regulatory umbrella, they were worried the regulatory tightening, if not carried out gradually, was likely to backfire as interbank liquidity would drain too fast, causing defaults and lead to a chain of failures.

Analysts warn that although bearish sentiment on China had flipped in 2017, with its equities posting respectable gains, currency stabilising, and capital outflow curbed, some of the risks and challenges the country faces in the coming year must not be overlooked.

Overtightening, which will send jitters from money markets to the property sector, is one of the key risks that China has to manage with caution.

Such risks have been given added urgency, as hundreds of China’s most powerful policymakers gather for the annual Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) to plot the economic direction and strategies for Chinese President Xi Jinping’s second five-year term.

Obviously, the central government wants to defuse the financial risks fuelled by wild credit expansion in the past years, but they are also aware, and are being told by banks, that haste will backfire

“Obviously, the central government wants to defuse the financial risks fuelled by wild credit expansion in the past years, but they are also aware, and are being told by banks, that haste will backfire. It certainly needs cautious and nimble policies to achieve the goal,” said He Dexu, an economics professor with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China’s top think tank.

Zhao Yang, chief China economist at Nomura, said that as the Chinese authorities push forward deleveraging and global central banks tighten their belts, further tightening in policy and liquidity will cause widening credit spread, diverged stock performance and surging risk premiums on the China market.

“Investors will see greater distinctions among good and bad companies, healthy and unhealthy banks, also industries relying or not relying on investment,” he said.

Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Securities in Hong Kong, said it would be unwise to overlook the downside risks of infrastructure investment.

“Our impression as economists is that while the consensus used to be overly pessimistic towards China, now it is starting to turn a bit too optimistic,” he said.

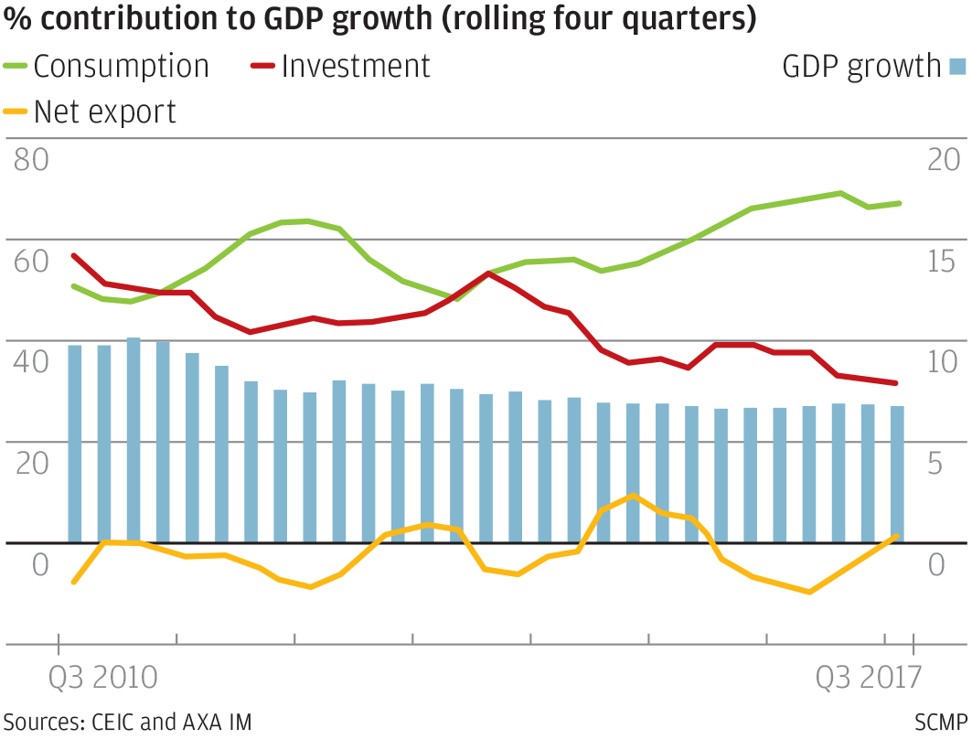

Infrastructure spending had been used as the main tool by the government to set a stable economic backdrop for the leadership reshuffle during the 19th party congress in October.

Now as President Xi has consolidated his power, and is poised to lead the country to embrace “high-quality” growth, “policymakers might be able to accept slower growth for infrastructure spending from next year, as the growth in the past five years is unsustainable”, he said.

“High-quality” growth is a growth pattern aligned more towards structural improvement rather than numbers.

Economists and analysts also differ on their views on the outlook for the Chinese economy.

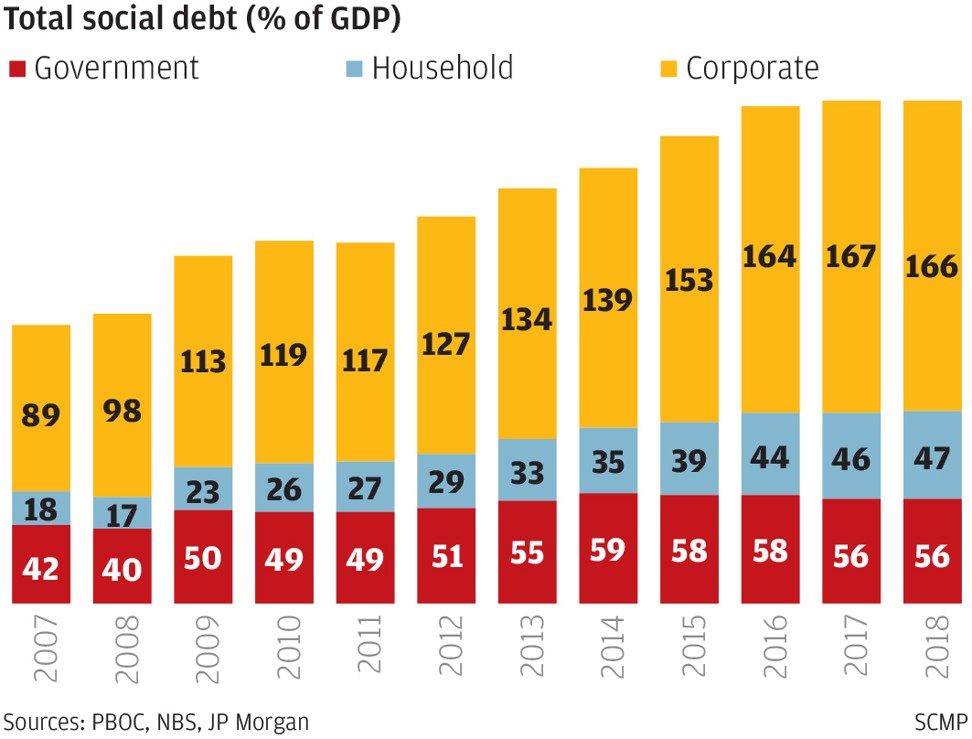

China has seen a deep imbalance in the economy and high level of debt, both building up so quickly that has been “never seen anywhere else”, Peking University professor Michael Pettis told the Fortune China forum held in Guangzhou earlier this month.

But unlike other countries where gross domestic product tracks the output of the economy, China’s GDP is an input by the government to achieve the goals made in advance by taking on as much debt as possible, which is unsustainable, he argued.

Meanwhile, the GDP growth target made by Beijing for 2017 (around 6.5 per cent) is on track to be achieved – as the economy registered a growth rate at 6.9 per cent in the first three quarters, and is set to end the year at 6.8 per cent.

Economic policies that China will adopt in 2018

On Monday, hundreds of top policymakers, regulators and provincial governors will meet in Beijing for the annual CEWC to discuss major economic tasks and policies, and most importantly, set the GDP growth target.

“The growth target for 2018 could be announced by the CEWC, but it is likely to be flexible between 6 to 6.5 per cent, as more structural reforms, more policies to tackle pollution and income distribution problems put short-term pressure on growth,” said Nomura’s Zhao, who projected around 6.4 per cent growth for 2018.

The International Monetary Fund had revised China’s GDP growth rate from 6.4 to 6.5 per cent in 2018, in its World Economic Outlook issued in late October.

Three key tasks for next year will include “addressing key risks and control macro leverage ratio, poverty reduction and significantly cut pollution emissions and improve the environment”, Xinhua reported after a Politburo meeting held on December 8.

“Concerns about an overheating housing market have abated after the authorities rolled out measures to stop prices from spiralling out of control and with steel-capacity elimination achieving 76 per cent of its five-year target, an easing off on the de-capacity campaign would be understandable,” he said.

But the official rhetoric and policy actions are becoming increasingly forceful on financial deleveraging and environment protection.

The official rhetoric and policy actions are becoming increasingly forceful on financial deleveraging and environment protection

The financial draft rules introduced by regulators in November, which are now being resisted by banks, is a major ongoing mission aimed at mitigating a growing systemic risk to China’s financial sector.

With regards to environmental clean-up, authorities are closing down factories and turning off coal-fired boilers. Starting next year, local governors will face audits of their records on natural resource management and environmental protection, and be held accountable for damages even after they leave the position.

Growth will decelerate in 2018, while policy operations will be bumpier as the authorities try to strike a balance between reforms and short-term stability, said Yao.

“If, and when, the two – reforms and stability preservation – are in conflict, we think the latter will take priority. Aggressive rate rises [due to deleveraging] and sharply cooling housing market [due to official tightening] will be duly countered by policy mitigation if they are seen as posing threats to macro stability,” he wrote in a note this week.