With headhunters in Malaysia fighting Chinese terrorists – a British Army major looks back at his life

Retired soldier Brian Finch recalls his time in the jungles of Malaysia, his role in Sino-British negotiations over Hong Kong’s future, and the day in 1989 when a million Hongkongers took the streets

War baby I was born in Crewe (in northwest England) in 1941. My father, Harold John Finch, was born in about 1910 and was in insurance. He was in the British Royal Air Force during the second world war and he divorced my mother when I was about five, so I didn’t know him at all. I met him once, many years later. My mother, Olive Elaine Finch, was a cashier in a butcher’s shop and we lived in Stoneleigh, in Surrey. I had one brother. He died some years ago.

Call to action I went to Glyn Grammar School, in Epsom, and then on to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst for two years. I was in the Combined Cadet Force at school and it was a natural progression from that. I joined the army in 1960. I was commissioned into the Middlesex Regiment and posted to the 1st Battalion, which was at Hamelin, in Germany. I was a second lieutenant. After 18 months in Germany, I was posted to Lydd, in Kent, and also spent a few months in Gibraltar before I applied for secondment to 1st Battalion, Malaysia Rangers, where I did some real soldiering for 2½ years.

The first thing we did was go up to the Thai border at the north end of the Malay Peninsula to operate against the remnants of the Chinese communist terrorists, which had been operating in Malaya during the Emergency (a guerilla war fought in the pre- and post-independence Federation of Malaya, from 1948 until 1960) but had then run to Thailand. By then, I was a lieutenant. We spoke Iban the whole time.

Sukarno’s Konfrontasi We were then posted to Borneo. Malaysia had been formed from the four independent nations or colonies of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah, and Indonesia’s president Sukarno didn’t like this. So he instigated what he called Konfrontasi, sending troops along hundreds of miles of border in Borneo.

He sent his troops up there to try to take over Sarawak and Sabah and make them parts of Indonesia. So the British and Malaysian army sent large numbers of troops to defend the border, and we were part of that. We were there for 18 months. In 1965, the battalion moved to Sarawak.

We were, of course, part of a much larger force, mainly British Army units. Our task was to patrol the border, which was a watershed along the high ground between Sarawak and Indonesian Borneo, which they call Kalimantan. The strategy was aggressive patrolling along the border to discourage incursions. My platoon had one minor skirmish with the enemy: an Indonesian unit tried to cross the border in the area where we were patrolling.

The leading members of my platoon engaged them with rifle fire, at which point they withdrew. Then we called on artillery support, which seemed to give them further encouragement to move back. Then Suharto got rid of Sukarno.

Speaking in tonguesI enjoyed studying French and German at school, and found them relatively easy. Later, when posted to Malaysia, I learned Malay, which is a pretty easy language at a colloquial level. Then I had to learn Iban, the language of my soldiers, without the benefit of any courses – none existed. But as the language is closely related to Malay, it was relatively easy to transfer. I guess it was this experience that made me realise I had a flair for languages.

Follower of fashion After Malaysia, I came back to what by then was the 4th Battalion, Queen’s Regiment, as the Middlesex Regiment had by then been amalgamated. We were in Holywood, County Down, in Northern Ireland. That’s where I met my wife, Gillian. She was working in a fashion shop, selling clothes.

I was there for about a year and would later come to Hong Kong to learn Mandarin at the Ministry of Defence Chinese Language School in Lyemun Barracks – now Lei Yue Mun Park and Holiday Village – from 1968 to 1971. Then, after learning Chinese, I was posted to Germany, in Werl, where we practised how to defend against a Russian invasion that never happened.

We watched [in June 1989] the amazing march of more than a million people. I’ve never seen anything so peaceful in my life. It was a worrying time. What didn’t surprise me was Deng Xiaoping’s decision to move hard against the students in Tiananmen

Run-up to the Handover I left the army as a major in 1978. We had two children, Cathy and Iain (who today live and work in Hong Kong). I joined the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and began relearning Chinese. I came to Hong Kong from 1982-87, and then again for a couple of years before the handover, doing political reporting for the Foreign Office. Because of my language skills, I was supporting the negotiators over the future of Hong Kong.

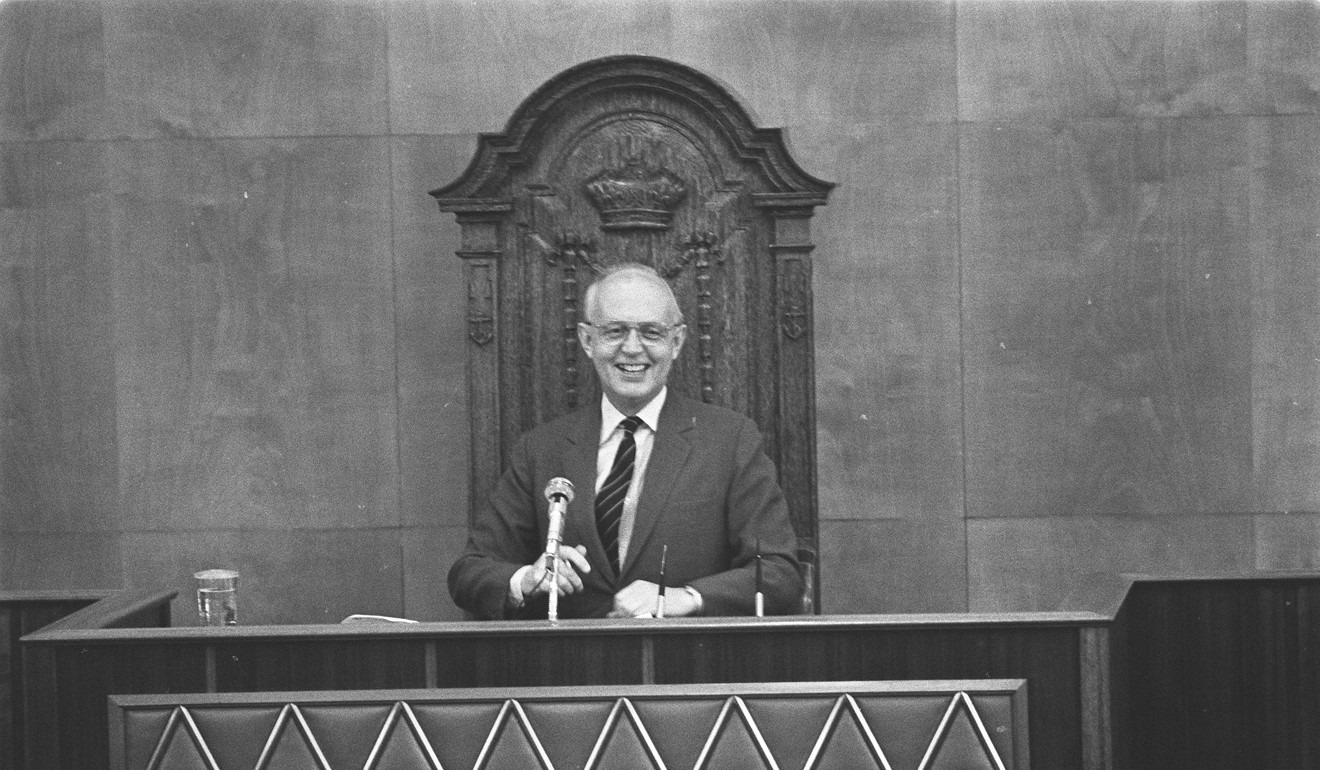

Teddy (Edward) Youde was governor when I arrived. Here was a man who was putting his heart and soul into sticking up for Hong Kong. When he died, the outpouring of grief was incredible. Thousands turned out to show sympathy and support.

We watched (in June 1989) the amazing march of more than a million people. I’ve never seen anything so peaceful in my life. It was a worrying time. What didn’t surprise me was Deng Xiaoping’s decision to move hard against the students in Tiananmen.

The Lisbon Maru was a Japanese troop ship that bore no markings showing it was carrying 1,834 prisoners of war from Sham Shui Po POW Camp to Japan (during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong) and was torpedoed by an American submarine on October 1, 1942, off the coast of Zhoushan (in Zhejiang province).

I recently completed a translation of A Faithful Record of the Lisbon Maru Incident from Chinese to English. This is an account of the incident through the eyes of courageous Chinese fishermen who rescued hundreds of prisoners of war from the sea, including many from the Middlesex Regiment. The fishermen also managed to hide three British men and help them escape and travel 1,000 miles (1,600km) across China to Chongqing.

I came to know the Lisbon Maru Association (who conducted the interviews) when I was working in Hong Kong and have worked closely with them since then on educating people about what happened.