Malaysia boleh: Mahathir’s return to power is more than a palace coup. It is a new era of hope

The victory of Pakatan Harapan has broken a barrier in the Malaysian psyche, raising hopes for a recalibration of the country’s race-based politics

The catchphrase “Malaysia Boleh” or “Malaysia Can” evolved as a national slogan in the early 1990s, rallying citizens around the proud vision of a tiger economy aspiring to developed nation status. Over time, it came to be used by those very citizens in a mocking tone, deriding their Southeast Asian nation, and especially its government, for its bumbling ways.

But since the night of May 9, spirits have been soaring again as Malaysians try to grasp, still in disbelief, the potentially monumental changes they have set in motion.

Mahathir sworn in as Malaysian prime minister

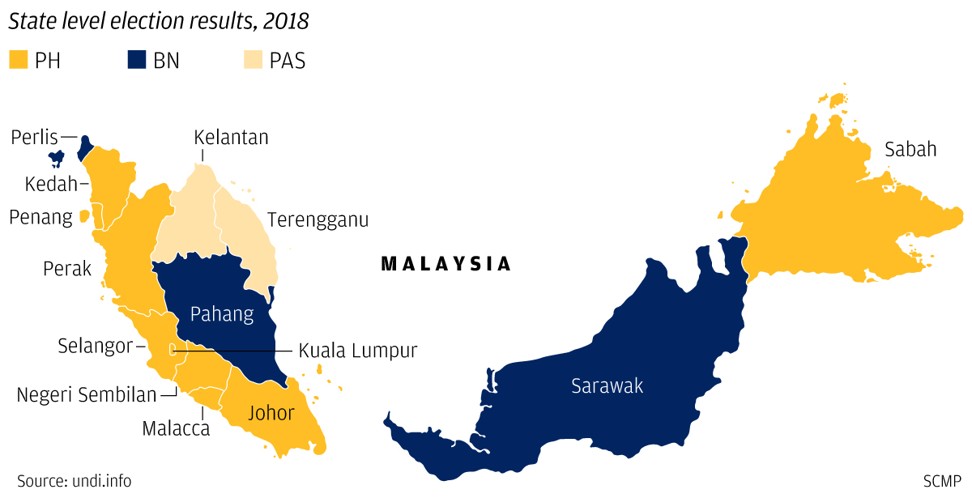

Malaysia is on the cusp of a revolution from above, as its 14th general election finally ousted the hegemonic coalition that has ruled without interruption for six decades. The Barisan Nasional (BN) alliance, led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), lost decisively at both the federal and state levels.

Surveys will probably show that people’s anger with the state of the economy, including the hugely unpopular Goods and Services Tax, was the main reason behind BN’s devastating loss of popular support.

But ground-level discontent with BN is nothing new. A courageous and dogged protest movement emerged two decades ago, starting with Reformasi and morphing into Bersih. They deserve credit for never giving up the dream of change.

Ironically, Malaysia’s new prime minister-elect, Mahathir Mohamad, is the very leader whose stranglehold on the polity from 1981 to 2003 unleashed the Reformasi movement that at one point saw citizens tear-gassed on the streets of the capital. He is now the leader that Malaysians yearning for change are banking on.

This stranger-than-fiction twist of fate points to the fact that this momentous event has as much to do with the tumult at the very summit of Malaysian politics, as grassroots discontent. It probably would not have occurred but for the brazen excesses of ousted Prime Minister Najib and his wife, which were too much even for the high-living UMNO elite to stomach.

Mahathir, the Malaysian dictator who became a giant killer

Pundits kept going on about how 1MDB was too removed a debacle for rural Malays to grasp. But there was a creeping sense of a nation shamed by its leader. The Malay proverb came to mind: “Kerana nila setitik rosak susu sebelanga” – “a drop of ink taints the whole pot of milk”.

Najib appeared tone deaf, letting on that he ate quinoa rather than rice, and allowing anecdotes about his wife’s lavish spending to feed the gossip mill.

Yet, for a while it looked as if Najib had grown too big to fail: backed by his incomparable resources, he quashed one challenge after another.

In 2015, he fired detractors from his Cabinet, including his then deputy, Muhyiddin Yassin, who had openly criticised him over the financial fiasco, and Rural and Regional Development Minister Mohd Shafie Apdal. Both later became key leaders of the opposition movement against him. But back then, it seemed Najib was untouchable.

What Malaysia’s Mahathir has in common with Winston Churchill

Najib also removed then-Attorney-General Abdul Gani Patail, who had led a high-level probe into allegations that money linked to 1MDB was deposited in his personal accounts.

During the campaign, the imbalance in resources was plain to see: on street banners and full page advertisements, BN blue was everywhere, with Najib’s smiling face and outstretched arms that seemed to say, give me more. Behind the scenes, he seemed to have a well oiled machinery, including imported spin doctors.

Such was Najib’s aura of financial invincibility that even observers who spotted a rising opposition tide feared he would steal victory from the jaws of defeat, including by inducing defections and stuffing ballot boxes. An opposition spokesman in Sabah said to This Week in Asia last weekend: “If the ballot boxes are not full, anything can happen.”

Ultimately though, voters handed him such a decisive blow that even he must have realised the situation was beyond salvation. At his press conference on Thursday, making his first appearance after the body blows to BN, Najib said the results proved that contrary to the scaremongering, his camp had acted honourably.

Is Chinese money an issue? In Malaysia, only at election time

Najib did not mention his other singular achievement. He accomplished something nobody else did – he managed to unite sworn enemies who had spent half their careers plotting against each other. In Najib, leading politicians found something they could all agree on: they reviled him even more than they did each other, and they wanted him out.

The outcome was a wave of unlikely alliances and significant gestures of compromise.

Muhyiddin allied himself with Mahathir when the latter set up his new Malay-based Parti Pribumi Bersatu in 2016. But the turning point that defied belief was the reconciliation between Mahathir and his former deputy, Anwar Ibrahim.

Mahathir had sacked Anwar over the management of the Asian financial crisis of 1998. Anwar, a fierce orator who made his mark as a charismatic student leader, promptly summoned all of his political capital to lead the Reformasi movement against Mahathir.

Anwar was later arrested and thrown into prison on sodomy charges, staying behind bars until 2004. He is now in prison serving another term, following charges levelled during Najib’s era.

Under the pact with Mahathir, Anwar will become prime minister in two years. He is due out of jail in June and a royal pardon will be arranged to let him run for election and enter Parliament.

Cynics will say this is nothing more than musical chairs. The music has stopped, Najib is out, but it’s the same old elites now sitting pretty.

But that would be to grossly underrate the significance of this change of government. The acts of compromise made by all sides required a giant leap of faith and a stout conviction that sworn enemies can reconcile and a commitment to focus on salvaging the future, not ruing the past.

Mahathir’s return to electoral politics opened him to attacks that he was power-hungry and an old man overstaying his welcome, risking his legacy in the process, as even this commentator wrote when he formed his new all-Malay party.

Anwar and his family had to put aside decades of hurt and anger towards the man behind their husband’s and father’s jailing. In the lead-up to the elections, This Week in Asia interviewed daughter Nurul Izzah, 37, who smiled and laughed when she admitted candidly it was not an easy decision. “But we did it for the country,” she said, adding that her father remained throughout an “irrepressible optimist”.

She revealed the inside negotiations in crafting their election plan and how Mahathir had railed against the oppressive rules set up by the Election Commission. “We wanted to say, well, you were in charge!”

The other political party that had to undergo a wrenching reconciliation with the emerging opposition configuration was the Democratic Action Party. Its veteran leader Lim Kit Siang and son, Lim Guan Eng, chief minister of Penang, were detained without trial under Operation Lalang, a national security swoop undertaken by Mahathir in 1987. Guan Eng spent another year in prison in 1999 for sedition, again during Mahathir’s era.

The DAP also suffered a near-permanent reputational burden of being cast as an anti-Malay, pro-Chinese party, sparking fear among Malay voters.

During the campaign, it sacrificed its much-beloved rocket logo to campaign under one logo – the Keadilan party logo – to foster greater unity and voter recognition. It was a gesture that was appreciated by older Malay voters especially.

All in all, these compromises indicate that Malaysia may be entering a new era when various communities are prepared to budge on stubbornly held positions in order to progress. It is this hope that makes the return of Mahathir to Putrajaya much more than just a palace coup.

What is within reach is nothing short of a recalibration of Malaysia’s race-based politics.

There have of course been attempts before to forge a multiracial party. The late founder of Umno, Onn Jaafar, set up his own multiracial Independence Party of Malaya in 1951 after he left Umno disenchanted with its race-based slant. Anwar’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat, set up in 2003 by his wife Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, while he was in prison, is another attempt.

It pledged a multiracial Malaysia but seemed to run out of steam in recent years. The Pakatan Harapan alliance appears more promising, a confluence of characters whose causes coincide with the electorate’s concerns. The camp includes Keadilan as well as Mahathir’s Parti Pribumi Bersatu, which is Malay-based, and DAP, a party that had started fielding non-Chinese candidates with some success.

Pakatan will be more multiracial than BN, in which the Malay nationalist Umno was the undisputed big brother. But recognising the realities on the ground, Pakatan will not stray from the core position that bumiputras’ status must be protected, or that Islam is the country’s official religion.

Malay fortress and ‘precious jewel’ Johor falls to Pakatan Harapan

So it was that last Thursday at the end of a rally in Putrajaya, the seat of the federal government, as Mahathir had just wrapped a speech to rapturous applause, a DAP man, clearly Chinese in appearance, took to the microphone and began speaking in perfect Malay. As the crowds began dispersing, an undeterred Anthony Loke, the candidate for Seremban, pledged that Pakatan would protect the special position of the Malays, the role of Islam and the Malay language and culture.

Similarly, at the same rally, DAP candidate of Segambut, Hannah Yeoh, dressed in the Malay traditional baju, appealed to Malay civil servants not to be fearful of embracing the opposition. In a moving tribute, she invited her teacher, Cikgu Raja Kamaruzaman to be on stage. She thanked him for calling her when she first entered politics a decade ago and said he was on her side.

Malaysia has certainly not entered an era of post-racial politics. Far from it. But there are a shifts afoot that may be more acceptable to minorities without causing Malays undue anxiety.

According to early indications, young voters went in droves to the opposition, regardless of race. If this is the case, the desire to not obsess and be fearful always of the other might be developing.

Now comes the practical difficulties of governing and realising a vision, a hope into workable compromises that leaves no group feeling cast aside or as second class citizens.

As Mahathir himself underlined at his press conference on Thursday, the path ahead will be difficult and he has to work with the heads of four parties. But he also made clear how the parties in Pakatan had signed a document pledging to protect the position of the Malays and in a jibe said: “I don’t see MCA, MIC signing this document.” MCA and MIC are respectively the Chinese- and Indian-based parties in Barisan.

The new balance will have to work on protecting the special position of the Malays without giving Malay elites carte blanche to enrich themselves.

Similarly, preserving Islam as the official religion must mean making it a source of inspiration for a just and moral order, without threatening the religious freedom of non-Muslims.

Mahathir himself has pledged to protect minorities. On the campaign stump, he promised to help marginalised Indians.

The days ahead will be riddled with challenges and some compromises may well be put aside. As Mahathir himself said, this time, he would use the opportunity to right some wrongs he committed while in power. The horse-trading and jockeying for positions will guarantee that some principles proclaimed from the rally stages will be set aside in the name of maintaining cohesion.

BN supporters laughed contemptuously at the idea of old enemies sticking together. How long can Pakatan Harapan hold together is the big question, once the details of swearing-in are sorted out in the coming days and assuming no trouble ensues.

Whatever happens in the coming weeks, there can be no doubt that a major psychological barrier has been breached: there can be a Malaysia without an Umno or a Barisan at the helm.

The electorate resisted money politics and fought to have their say despite numerous attempts to suppress the vote. After years in the doldrums, feeling that elites could abuse their power with impunity, ordinary citizens can now believe again in their democratic power to change their destiny. Malaysians boleh.