‘Worse than death’: the children who survived the battle for Okinawa

More than 70 years on from the fighting, the horrors of war still haunt the survivors. For them, there may be one thing worse than dying in war: surviving it

Kiku Nakayama was 16 years old in 1945 when she was handed two grenades by a soldier from the Imperial Japanese Army. She was told to blow herself up if she came into contact with US troops.

“Japanese soldiers told us that the American forces would rape and burn alive any women they saw. I did not have the courage to pull the pin but many of my classmates did,” says Kiku, 89. “Every day I wonder why I survived and not them.”

Last month marked the 73rd anniversary of the battle of Okinawa. Many survivors such as Kiku are still trying to come to terms with the atrocities they experienced.

‘Chinese agent’ and other insults the Okinawa governor lives with for opposing US base

Outnumbered by American forces, Japanese soldiers handed out grenades to civilians describing them as “benevolent gifts from the Emperor”. Other accounts detail them using civilians as human shields, decapitating babies whose cries threatened to give away secret hiding spots and stealing food meant for women and children.

Hitler’s Germany was on the brink of an unconditional surrender in 1945 when America turned its attention to the Pacific in an attempt to stop the last of the Axis powers by invading mainland Japan.

During the battle of more than 80 days that lasted until June 22, 1945, Japanese and American troops obliterated the island chain in a cacophony of mortar and machine-gun fire under unforgiving monsoon rains, resulting in the deaths of more than 150,000 Okinawan civilians – almost a third of the indigenous population.

Meanwhile, the Americans suffered more than 49,000 casualties, including 12,520 soldiers who were killed. No Marine unit in the history of the corps would suffer as many casualties as the 29th Marine Regiment that went into battle at Okinawa.

Historically and culturally at odds with mainland Japan, Okinawa continues to be viewed as an outsider by the Japanese government, a geographic blip of the Pacific that was always a little too far from itself and a little too near Taiwan.

Meet the ‘rough country boy’ standing up to US base plans in Japan

Now in their twilight years, a disappearing generation of war survivors are speaking up before their stories are lost forever.

Between the devil and the deep blue sea

On the night that 84-year-old Kiyoshi Uehara thought for certain he would die, the sky above was a blanket of primrose purple freckled with endless stars, but there was no moon.

“When death is near, you stop worrying about how it will come and start noticing the small things, like the night sky,” he says.

It was August 22, 1944, and a 10-year-old Kiyoshi had been drifting for six hours off the frigid north-western coast of the East China Sea on a plank of cedar wood no bigger than a cupboard door when this realisation hit.

Part of an emergency evacuation convoy from Okinawa to Nagasaki, the ship he was on, the Tsushima Maru was torpedoed by the RSS Bowfin, a US Navy submarine.

The civilian ship was meant to act as a safe passage for Okinawa citizens.

It had been carrying 1,661 evacuees – women, children and the elderly – when it was attacked shortly after 10pm.

Of these, more than 1,000 children would lose their lives; only 59 people survived the attack.

The battle of Okinawa would commence eight months later, but this would be the first show of force by the Americans – to innocent, unarmed civilians nonetheless.

After drifting out in the open sea for five days, Kiyoshi was experiencing severe dehydration and fatigue.

With the midday heat upon him, he was struggling to keep afloat when something cold and bristly brushed against his right shin.

The real reason Japan’s emperor wants to abdicate

Looking down, he saw the face of a partially decomposing body. It belonged to a 7-year-old girl.

“A teacher and his wife who were drifting not far away from us had lost their daughter a few days back.

“They didn’t want to abandon her body in the ocean so they tied her body to a rope and fastened it to their bodies.”

After drifting for seven days in the East China Sea, Kiyoshi washed up unconscious on a rocky shore near the village of Yamato in Kagoshima – almost 354km away from where the ship sank.

Nearby villagers took him and a few other survivors to a nearby hospital where he was tended to by doctors who could not believe that he was still alive.

After recovering, he was taken to a police station in Naha City where government officials warned him and other survivors not to breathe a word about the sinking, out of fear that it might spark a widespread loss of confidence in Japan’s war aspirations.

“Because we never spoke about it, so many people never knew why they never saw their children again. “You know what’s worse than death?” he asks.

“Not having closure.”

War is forever

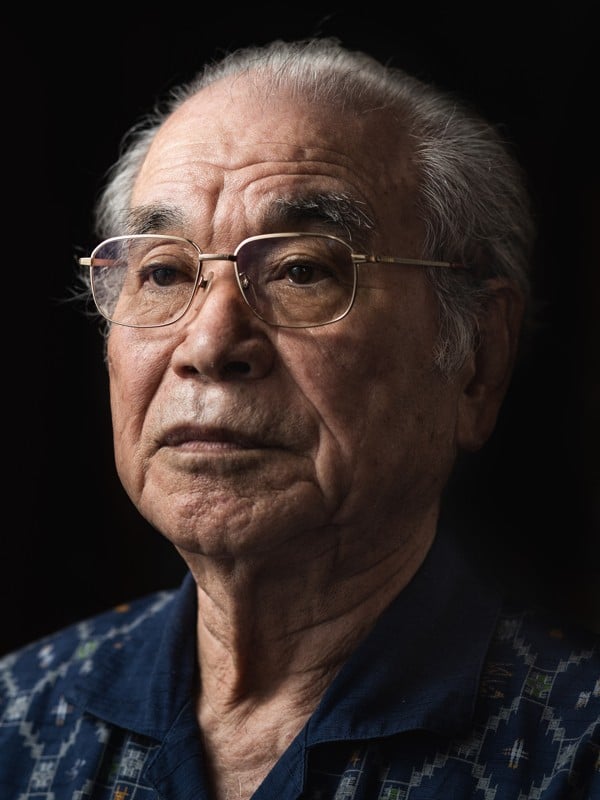

Masayoshi Oshiro, 85, is slowly losing his mind.

“Over the years, I have forgotten the faces of friends, family and even where I live sometimes. But the war – that’s different. I remember the war as if it happened a few hours ago,” he says with a slight smile.

It was a quarter after one on a dusty February afternoon in 1943 when Masayoshi realised his life would never be the same again.

After his school’s headmaster sounded the bell for an emergency assembly, the students saw neatly packed bamboo poles at the front of each class line.

“We all thought we were going to play games. None of us knew that we were preparing for a lesson on how to spear American soldiers in close combat,” he says.

Having bombed Pearl Harbour two years prior, the Japanese government was certain that US retaliation would come.

But not willing to sacrifice troops or leave the mainland in peril, they decided to mobilise ordinary citizens – many as young or even younger than 11-year-old Oshiro.

What ensued was a two-year war preparation programme for the teachers and students alike.

Apart from learning how to effectively shave off the ends of a bamboo pole using a home knife, the programme included daily four-hour sessions in which students would bayonet effigies of American soldiers made out of gunny sacks filled with hay. “I felt empowered because I was told I was doing this to protect the Emperor of Japan. What I didn’t know at that time was that the Emperor of Japan had no plans to protect me,” he says.

He would face the brunt of Japanese prejudice against Okinawans first hand in the middle of May, seven weeks into the war.

Anti-US rage: rapes, murders, accidents, and now this in Okinawa

Seeking refuge from the aerial bombardment of American fighter planes above, he was hiding among tombstones in a public cemetery not far from the Naha City area, when three Japanese soldiers yanked him by the collar.

He was told to give up his hiding spot and leave, or stay and be bayoneted to death.

Another memory that has plagued him for years is that of the comfort women who were interned by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Okinawa war.

Comprising mainly of Korean, Japanese and Okinawan women, they served Japanese soldiers in makeshift red light areas often for little or no pay.

In the day, they went around begging people for food or water to drink because they had no one else to depend on.

Out of a sense of compassion, he would offer them extra potatoes or tapioca whenever he could.

“At times, I would look at them when they thanked me and I would notice that their eyes had no more life in them.”

I think about him everyday

Whenever Kiku Nakayama, 83, talks about the war, it is in soft, hushed tones.

It’s as if the spectre of war that continues to hover around her might come to life again if she dare raise her voice, as if talking just one decibel higher might reawaken demons she has fought hard to put to bed over the years.

“Do you know what is worse than dying in a war? It is surviving it. Because every other day after that, you think about it,” she says.

At only 16 years old, Kiku was conscripted to be part of the Shiraume Nursing Corps, a female medical unit put together by the Japanese army that tended to sick and injured soldiers.

The unit comprised of 56 students of the Dai-ni Koto Jogakko, an all-girls high school.

Twenty-two of the students would die in the following few weeks because of the fierce fighting.

Realising a lack of medical staff on the island, the Japanese government mobilised schools around Okinawa to get students to serve as nurses and medical staff.

Kiku was into her 18th day of medical training when she and four other girls were asked to serve as medical assistants to a doctor at a cave near Naha City. “Some soldiers came in with their guts spilling out, some had their entire faces burnt away because of the shrapnel. It was truly hell on earth, in every possible way,” she says.

Wailing and moans emanating from the caves would go on for days on end and often soldiers turned delirious because of the severity of their injuries.

The dark and dank environment meant that it didn’t take long for infections to set in.

With antiseptic in short supply, maggots would start setting in the wounds. Amputating limbs was the only option.

Surgeries were almost always done without anaesthesia, and all were performed at night because the sound of the US airplanes above helped mask the screams.

On her sixth day on the job, she was assigned to assist on a surgery, on a rusty metal table that had been secured to the ground using rocks.

‘Pollution by tourism’: How Japan fell out of love with visitors from China and beyond

“My job was to hold down the shoulders of injured Japanese soldiers when their limbs were being amputated by the doctors. I used to get a lot of scolding from the head doctor because I couldn’t bear looking at them suffer and I would look away.”

In June, there were rumours that an air strike was looming so they had to evacuate the caves. They successfully evacuated about 80 injured soldiers – there was only one soldier left. He had lost his left leg to a mine and he was screaming in pain.

Kiku was one of the last few to leave the caves and he asked if she would be coming back to get him. “I said ‘yes’ even though I knew this was the last time I would ever see him,” she said.

“I think about him all the time.”

Deeply and swiftly

Masako Nakazato was 18 years old on August 22, 1945, when she was handed a knife and told to run it deeply and swiftly across her flesh just above her clavicle.

A deactivation order had been sounded by the American troops a few hours prior and Japanese soldiers began spreading rumours that Americans would rape and burn the women they found.

Hundreds committed suicide by jumping off cliffs or blowing themselves up with grenades handed to them by soldiers.

There are even accounts of family members beating their children to death.

In the Chibichiri-gama or “mass suicide” cave located in the middle of Yomitan village in Okinawa, 83 civilians, mostly families, killed themselves on April 2, 1945, for fear of being captured by US soldiers.

Today, the cave serves as a memorial to the families.

Masako was in a similar cave on the northern side of the island when a nurse handed her the rusty knife.

Why is racism so big in Japan?

“We had run out of cyanide and grenades so the knife was the only solution. A few other ladies had used it to kill themselves so by the time it reached me, it was drenched in blood,” she says.

Before she could do it, an injured Japanese soldier who was by her side crawled up to her and told her that the Americans were not going to kill anyone and that they were actually here to liberate the Okinawa citizens.

Masako was part of the Himeyuri Student Nurse corps, a medical support group formed by soldiers who were mobilising Okinawans for the war ahead.

Girls between the ages of 15 and 19 years old had been recruited from two high schools in Naha to take up jobs as war nurses with minimal training. More than half the 222 women and girls who were part of the corps never came home.

According to Masako, now 92, most of her friends who had survived the war killed themselves after the deactivation order sounded.

This was because of Japanese propaganda spread by soldiers claiming that the American soldiers would kill them. “My friends believed the Japanese soldiers and went to kill themselves. I was saved at the last second and I am here today. Every day, I regret it that I am alive while they aren’t,”

In one particular incident, she recounts how Japanese soldiers ordered her and other civilians hiding in the caves to walk out into a hail of bullets.

They wanted to know where the snipers were positioned so they used civilians as human shields.

“We were innocent schoolgirls and they made us walk into enemy fire so that they could save themselves,” she says.

“How will I ever forgive them?” ■