Shoko Asahara: my memories of how Tokyo subway sarin attack spread terror one day in March 1995

Post journalist Charmaine Chan recalls the fear that gripped Tokyo residents, glued to their TVs in a pre-internet age as police hunted for Aum Shinrikyo cult members in the weeks after deadly gas attack

One of the worst aspects of my newspaper job in Tokyo was the bird-call starts. To be at my desk by 6.30am meant catching a 5.30am train and changing lines twice to reach the Asahi Shimbun headquarters in Tsukiji. March 20, 1995, however, changed my attitude to the early shift.

That day, during peak-hour Monday morning traffic, members of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult gassed the city’s subway system, killing 13 people and injuring thousands more.

Led to the noose in diapers: the strange life and death of Shoko Asahara, murderous guru behind Tokyo sarin attack

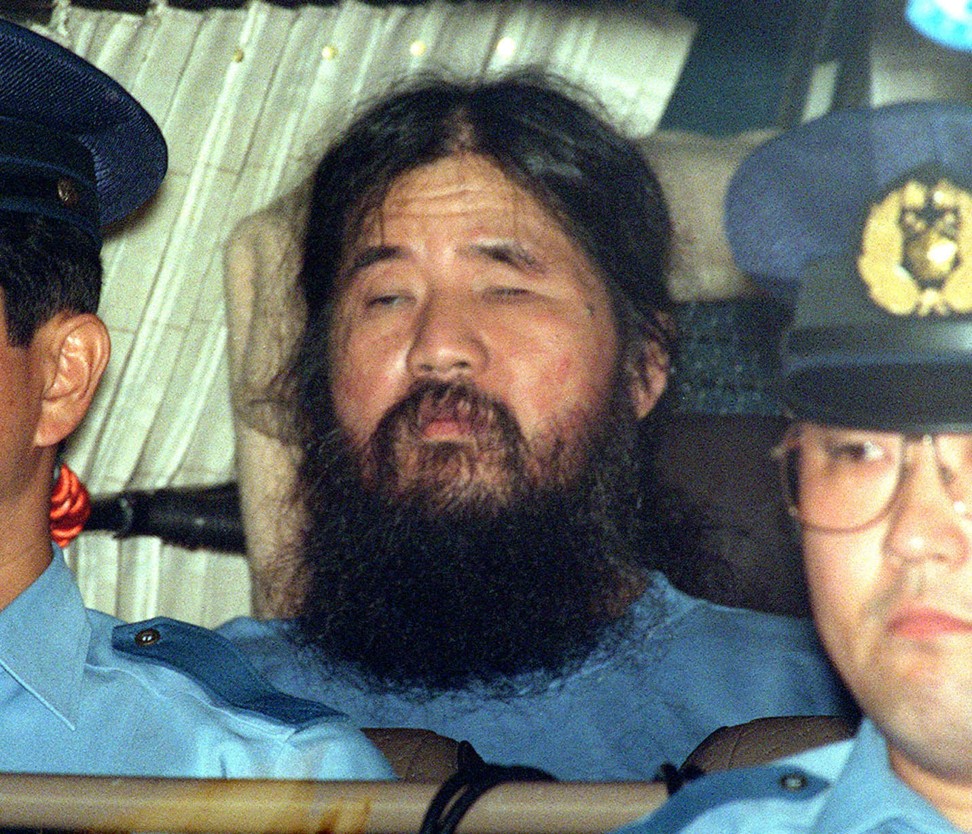

The media provided near round-the-clock reports, culminating in the capture of the corpulent, near-blind, self-proclaimed guru. On May 16, 1995, police discovered him in a coffin-like cell at the group’s headquarters in Kamikuishiki, a hamlet at the foot of Mount Fuji. Television cameras on that misty morning broadcast scenes few would forget: a couple of hours after the day’s drama began, the countdown to finding Asahara started with reporters gasping: “The doors are being forced open,” then shrieking into microphones as his location was confirmed.

An unkempt Asahara, dressed in pink robes, was ejected from his hideout still hugging wads of Japanese yen, and driven away in a blue van at 10.35am. With helicopters buzzing overhead, hundreds of reporters giving chase and crowds perched on highway overpasses watching the spectacle, it recalled the surreal tailing of O.J. Simpson a year earlier on a Los Angeles freeway. Only this was Japan, known for its law-abiding citizens and often ridiculed for instilling in them an unshakeable will to conform.

During the weeks leading to Asahara’s detention, Aum’s nefarious operations came to the fore as related crimes took place, often in the public eye, cowing a populace that had never before feared catching public transport or indeed living in the busy metropolis. Millions of people tethered to their television sets, myself included, were chilled by other killings and assassination attempts in the city, including the shooting of a police commissioner in front of his home by a man who fled on a bicycle (the victim, who survived four gunshots, had led the much-anticipated raid of Aum’s headquarters on March 22), and a murder captured by cameras of a cult lieutenant.

The fax our intern received from a chemist at The American Pharmacy – of the complex atomic arrangement of sarin – resembled what we would come to understand about Aum, a group with business interests spanning the globe and reported links to the yakuza. This we learned in the aftermath of a televised killing on the evening of April 23, when Aum’s “science minister”, Hideo Murai, was knifed as he was forcing his way through a phalanx of police and reporters besieging the group’s Tokyo office. The assassin, a thug affiliated with the Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza group, stabbed his victim repeatedly until he collapsed in the middle of the scrum.

The public slaying took place more than a month after the sarin strike on the subway, and followed mass arrests of cult members – a grim nationwide hunt Tokyo residents couldn’t help but follow as X marks indicating “captured” started appearing on mug shots posted at stations. The chemical attack also led to platform bins being sealed and, later, the installation of cameras to deter reprisals.

We used the inappropriately cute moniker only to lighten the pessimism fuelled by unending reports covering everything from the electrode-filled helmets members wore to synchronise brain waves with Asahara and the 50 degree Celsius baths wayward followers were forced to enter to the drinks made from the brewed beard clippings and semen of the guru, which sold for high prices. Fact may have been laced with fiction but, at the time, anything seemed possible.

That three stations I used frequently had been danger zones – Ikebukuro, where one of the five Aum teams boarded the train on the day of the sarin attack; Higashi-Ginza, one of the many stops where poisoned passengers lay convulsing and temporarily blinded while awaiting ambulances; and Shinjuku, where thousands could have been killed, according to reports – was reason enough to find alternative routes home. So instead of heading for the closest station every day, I often walked 15 extra minutes to Ginza to board the Marunouchi line (unfortunately, one of the three targeted in the attack). That meant using two of three arteries I needed to reach home, which, in my mind at least, was safer than following routine.

When I heard that Asahara had been executed 23 years after he instigated one of post-war Japan’s gravest crimes, relief was the initial sensation. But then I remembered how brief the reprieve had been after he had been captured. Even as people were grabbing special newspaper handouts published to announce his arrest, another act of violence was in motion. Hours after Asahara’s detention, a parcel bomb exploded in the offices of Tokyo’s then governor Yukio Aoshima. The blast blew off the hand of the person opening the package.

Which is why news in September 2006 that Asahara had lost a special appeal against his death sentence (having been ruled legally sane and thus responsible for his actions) was followed by police swoops on 25 locations connected with Aum, which by then had changed its name to Aleph.

Now, I fear, having been hanged, along with six disciples, without ever explaining his motives, Asahara will live on oddly as a kind of martyr.