China’s economy isn’t opening. It’s closing – and it’s hurting itself

An advanced economy requires ideas, interaction, and competition – all things that Beijing is shutting down and turning away from

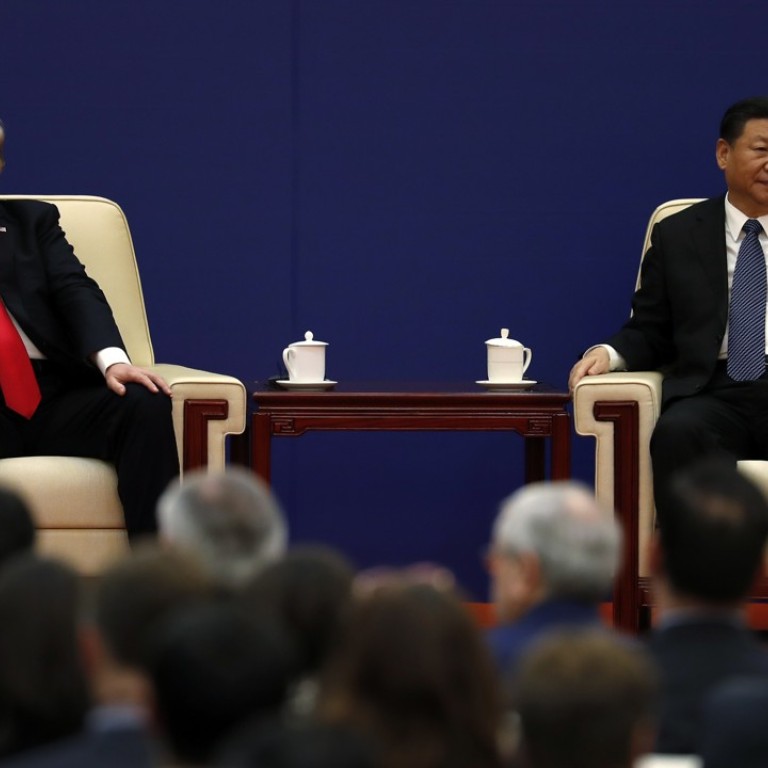

His speech at the forum, which is often referred to as “Asia’s Davos”, follows his widely lauded address to the World Economic Forum (the “real” Davos) in 2017, when Xi with the support of Chinese state media encouraged the world to see China as the new global defender of openness. But away from media events with global CEOs, the reality of Chinese openness appears radically different.

Despite the rhetoric, China remains a closed economy. A February IMF study on measures of trade and investment openness found that China was not only more closed than the average developed economy, but more closed than the average emerging market economy.

Trump versus China: is this the dawn of a second cold war?

Just this week it was announced that all scientific data generated in China would need to be vetted by the government before it could be published. If Beijing is seeking to attract high-quality research and development investment while demanding to control scientific data generated in China, it may want to rethink its openness mantra.

The closing of China is apparent in mundane ways with even domestic firms who want to be compliant. Toutiao – which aggregates news and videos from hundreds of media outlets – was shut down by censors for a few days this week. CEO Zhang Yiming said he would permanently shut down humour content app Neihan Duanzi. This came despite Toutiao already employing 6,000 censors and planning to hire 4,000 more. The so-called openness being touted at the Boao Forum seems far from the reality of business in China.

While Beijing may complain about American protectionism, Chinese regulators have done more to shut down Chinese investment abroad. Beijing’s words ring hollow regarding foreign intervention when it blocks most proposed outward investments by Chinese investors.

A nasty US-China fight is inevitable. But it needn’t be terminal

What makes this closing of the Chinese economy so unnecessary is its competitiveness. China has produced innovative tech giants at the cutting edge of technology. From robotics to consumer goods, China does not need the protectionism Beijing wants to hobble the economy with.

The closing of the Chinese mind is harmful for the evolution of the Chinese economy and China as a rising power. To be an advanced economy, it requires ideas, interaction, and competition – all things that China is shutting down and turning away from. ■

Christopher Balding has lived in China for nine years and has worked as a professor at Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School