Why China loves Jane Eyre, whether as a feminist manifesto, a history of colonialism or just a simple children’s bedtime story

Charlotte Brontë’s classic 1847 novel Jane Eyre was first published in Chinese as an abridged version in 1925. But it was the secret dubbing of the 1970 film during the Cultural Revolution where its story in China really started

Jane Eyre is huge in China – some say the novel is even more popular there than in its home country of England.

The novel, written by Charlotte Brontë in 1847, has been translated into Chinese multiple times and released in bilingual, illustrated, abridged and simplified editions, as pocket books and e-books, and as children’s bedtime stories.

The story of a martyr in Mao’s China: executed and her family billed for the bullet

The book is taught in Chinese schools and has been adapted into a long-running stage play and a Chinese opera. There are even historical romance manga inspired by governesses such as the novel’s eponymous main character that are popular on the mainland and especially in Hong Kong.

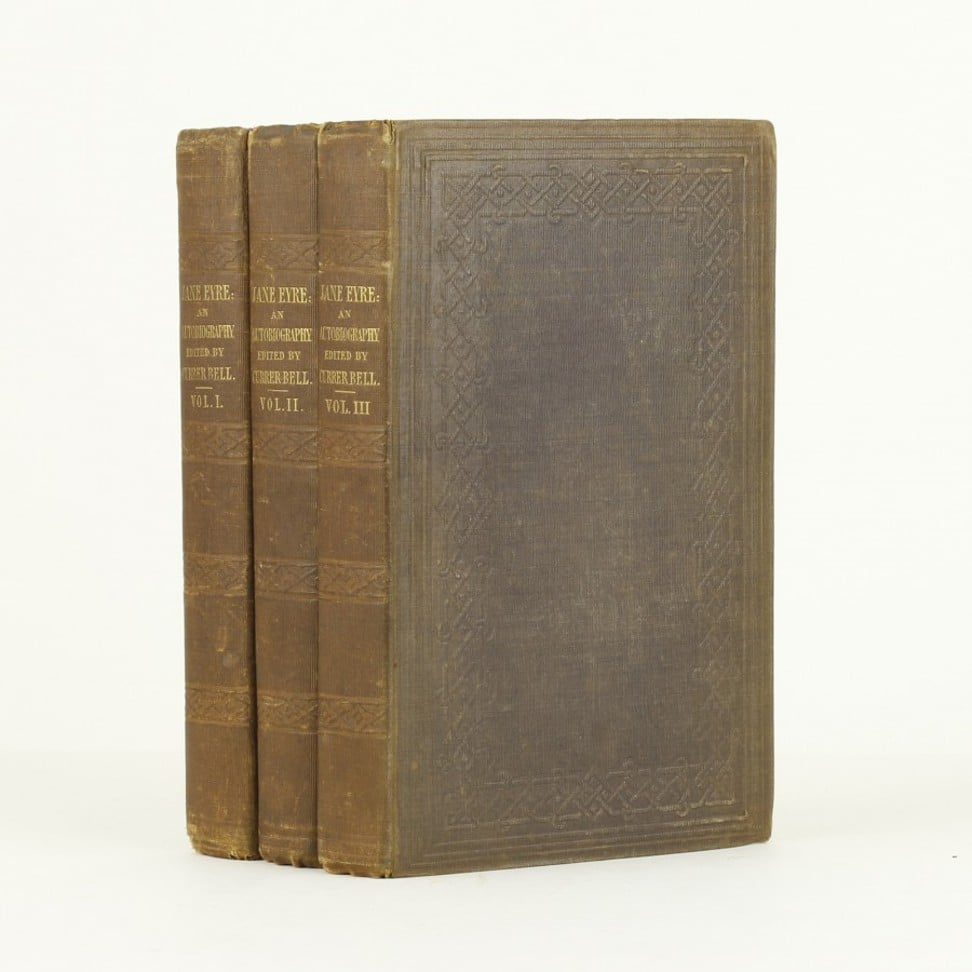

Last month, Brontë’s original hand-written manuscript went on show in Shanghai. The exhibition – which also included other treasures of English literature such as personal letters by T.S. Eliot and D.H. Lawrence, a draft of Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers and another of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet to Lord Byron – drew 20,000 visitors in a month. The show was part of a three-year programme by the British Library to foster dialogue and connections between China and the UK.

“We would like to enrich and expand our collaboration with China,” says Jamie Andrews, head of culture and learning at the British Library. “Our British collection is known and enjoyed there, and museums and libraries are opening up. There’s a huge demand for exhibitions and partnerships.”

Andrews says their team thought very carefully about which artefacts to put on show at the Shanghai Library.

“The Jane Eyre manuscript is often among the five most popular artefacts for British visitors, but we were also aware that Jane Eyre has a strong pull for Chinese audiences,” he says.

So what makes Jane Eyre so appealing in China?

Shouhua Qi, English professor at Western Connecticut State University and co-editor of the book The Brontë Sisters in Other Wor(l)ds, says the story really begins with the television film of the novel directed by Delbert Mann. Starring Susannah York and George C. Scott, it was released in the UK in 1970.

“The film was dubbed secretly into Chinese in 1975 during the Cultural Revolution by the storied Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio and was finally screened publicly in 1979,” Qi says. “At this time, China was opening to the outside world, and all things Western were gushing in. A renaissance of learning was sweeping the country, with a frenzied reading of books, both Chinese and Western classics, that had been banned during the Cultural Revolution.”

The first Chinese translation of Jane Eyre was published in Shanghai in 1925. It was an abridged version by Zhou Shoujuan, a popular writer from the “mandarin ducks and butterfly” school (frivolous love literature with flowery prose), who reduced the novel to a simple love story. While this version, and later full translations, were well liked, Brontë’s novel did not win the same regard as those by other Western novelists, such as Ibsen, Dickens, Tolstoy or Balzac.

But in post-Cultural Revolution China there was a “revolutionary reshuffling”, Qi says, and what had been dismissed as “petty-bourgeois” and trivial now acquired serious importance. “Readers used to dull, overtly propagandistic writings now relished what was new and different.”

Jane Eyre was seen [in China] as an anti-repression heroine representative of the proletariat class

The new market-driven economy also meant that literary magazines, scholarly journals and publishing houses blossomed in response to the ever-increasing demand for new literary products and interpretations.

Not only was Jane Eyre new and different, it was written in the realist style, which appealed (and still appeals) to Chinese readers. It also still fit certain themes popular at the time. The novel is a bildungsroman (a story that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the central character) that tells the tale of an orphan who suffers many hardships, grows up to be a governess, and falls in love with her employer, who she eventually marries.

“Jane Eyre was seen as an anti-repression heroine representative of the proletariat class,” says Lucy Liu Yangliu, an English master’s student at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). “The book’s famous quote – ‘Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!’ – was also in line with communists’ feminist side, which was arguably one of the very few achievements of this legacy – if there is any achievement at all.”

But for Olivia Xu Lingyi, who also grew up in China and is studying English at HKU, these readings can be reductive.

“I read Jane Eyre for the first time in its Chinese translation when I was at primary school. The heroine was celebrated as a paragon figure for young women, with her uncompromising conviction of her self-autonomy,” she says.

“I’m now ambivalent about the fact that the novel was introduced to me as an affirmative story about a young lady’s pursuit of independence and freedom. Jane’s complexities and charms extend beyond those orthodox virtues; they also lie in her rage, her bitterness and, of course, her famous dark sides.”

Teaching any complex work of literature at primary school level involves simplification. But the novel has withstood a variety of readings – more nuanced or less – over the decades and continues to inspire today.

Contemporary “neo-Victorian” fiction, including “governess manga”, picks up on many of the themes found in Jane Eyre.

Dr Elizabeth Ho at HKU has written extensively on the historical romance manga Emma by self-professed Anglophile Kaoru Mori, which represents London in 1895 with meticulous detail and historical accuracy. “The governess motif is popular because it deals explicitly with issues of class, sexuality, labour, gender and the cultural memory of canonical English literary texts such as Jane Eyre or The Turn of the Screw,” she says.

“The governess occupies a liminal space in the Victorian household – she is neither family nor servant – and is often young and unmarried. The anxieties of being around the ‘single woman’ who is seeking some kind of upward mobility are pertinent then and now.”

China’s online publishing industry – where fortune favours the few, and sometimes the undeserving

For Hong Kong readers, what also resonates today is the window the novel offers into their cultural yesterday.

“Jane Eyre’s popularity in Hong Kong results from the history of colonialism,” says Julia Kuehn, professor of English at HKU. “My students always stress that the history of Jane Eyre, which is set in the 1840s, is of course also their own: they like the novel as it tells them about life in Britain during the years that Hong Kong became a colony.”

A history of colonialism, a feminist manifesto, or a children’s bedtime story – the many readings attest to Charlotte Brontë’s skill as a writer of extraordinary complexity and depth. Jane Eyre may be a very English heroine, but she is a Chinese one, too.