Trump’s trade war on China: phoney or real, world will be the loser

If Trump sticks to his guns, his trade war could usher in a worldwide depression. Even if he’s just showboating (remember North Korea, anyone?), much of the damage has already been done

WATCH: Trade war threatens China’s love for American barbecue

If this really is the case, then workers and businesses around the world will be facing nothing less than the reversal of the trend towards globalisation that has done more than anything else to drive the world’s economic growth over the past 20 years. The result could easily be global recession, or even depression.

Optimists and pessimists both see support for their views in the 25 per cent tariffs on US$34 billion of US imports from China that went into force on Friday.

As trade war looms, the US looks confident. China, not so much

By themselves, these tariffs will have almost no direct economic impact. Assuming no substitution effects, they will raise the overall effective tariff rate on US imports from a weighted average of 3.3 per cent to 3.7 per cent.

By comparison, China – before Beijing’s promised retaliatory measures – imposes an effective tariff rate of 7.9 per cent.

In other words, say the optimists, the tariffs the US has instituted so far are largely symbolic; a bluff that can readily be negotiated away.

WATCH: The US-China trade war and its impact on consumers

They see several reasons to believe this may be what Trump intends. The most obvious is the president’s about-turn on North Korea, which saw Trump abandon his fiery rhetoric for what amounted to little more than a photo-opportunity that allows him to parade himself as a peacemaker.

Now there are hints Trump may prove similarly supple on trade. Last month he backed away from imposing sweeping restrictions on Chinese investments in the US. And last week Washington lifted an order banning US chip makers from selling components to Chinese smartphone company ZTE.

In short, say the optimists, Trump talks tough. But when implementation threatens to impose actual costs on the US, he has shown himself ready to drop his rhetoric and dial down the tensions.

The pessimists dispute this rosy picture. While they agree that the direct effects of the tariffs announced so far will be near-negligible, they argue that Trump has shown little inclination to alter course, and that his direction of travel is ominous in the extreme.

This school points out that trade policy is one of the few areas in which Trump has been consistent: ever since the 1980s he has been complaining that unfair trade practices undermine the US economy.

If Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods had simply been aimed at securing improved market access and better terms for US exports, the president would have welcomed Beijing’s recent promise to allow greater foreign investment in the financial sector and its cut in car import tariffs.

US-China trade war: bad for business is just the beginning

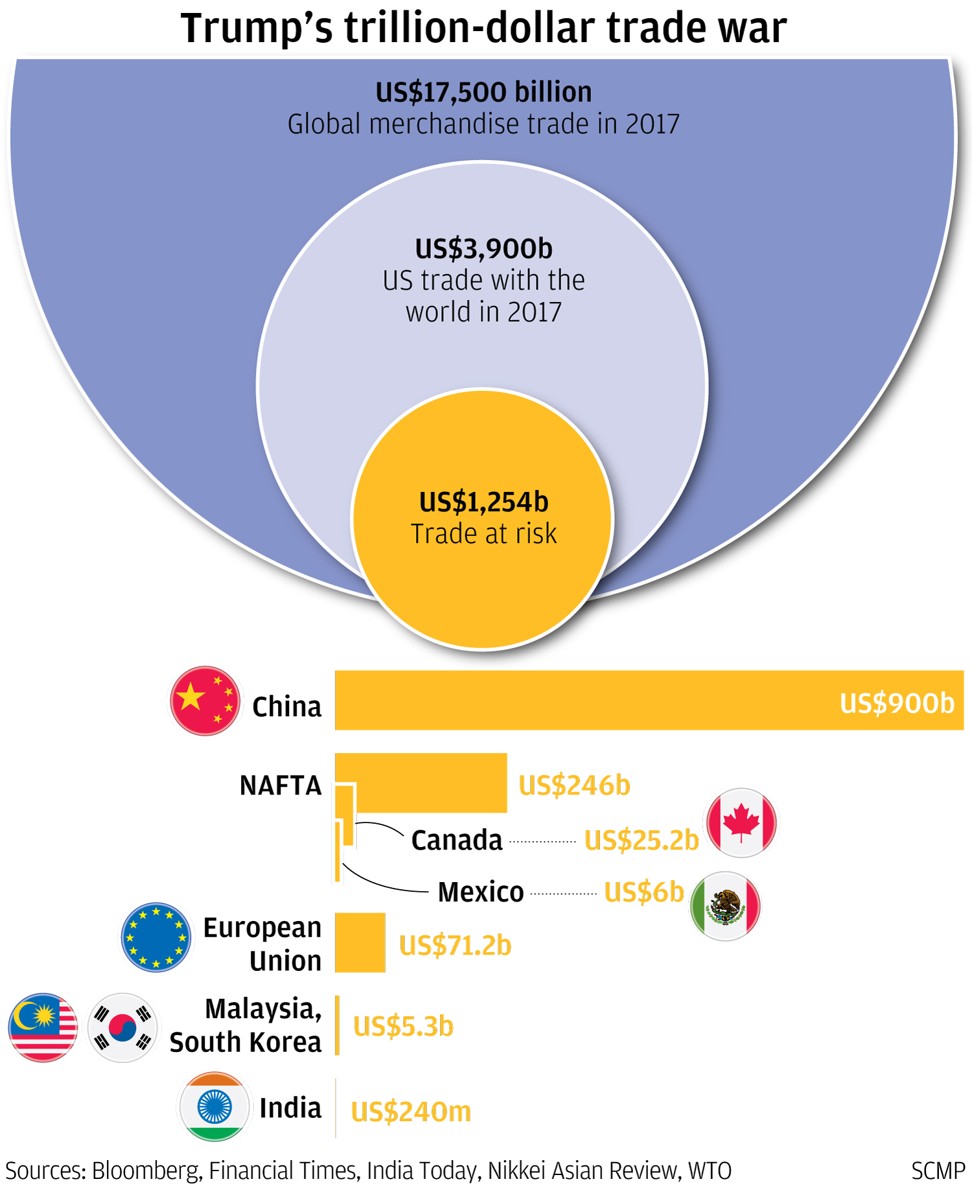

Instead the US administration is proposing to slap 25 per cent tariffs on another US$16 billion of Chinese goods in the coming weeks, with Trump threatening 10 per cent tariffs on an additional US$200 to US$400 billion of US imports from China should Beijing retaliate (which it certainly will – Beijing has prepared countervailing tariffs on US$34 billion of US farm products and autos, and a second round on US$16 billion of US petroleum and chemical products).

And the US isn’t only targeting China. Trump is also threatening to levy tariffs on US$300 billion of car and car part imports, largely from US allies, and to withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico, which would raise tariffs on a further US$600 billion of US imports. Together, these would imply an effective tariff rate on US imports of close to 10 per cent, a rate comparable with protectionist countries like Zimbabwe.

In short, say the pessimists, the Trump administration shows every sign that it intends to fight a global trade war on all fronts, against US strategic allies as well as against strategic competitors.

Who such a trade war would hurt most – the US or its opponents – is debatable. But the world economy as a whole would suffer grievously.

In particular, such a widespread trade conflict would severely disrupt the global manufacturing supply chains that have developed over the past 20 or so years.

Today, such a supply chain might see a microprocessor designed in the United Kingdom and manufactured in the US exported to China to be married in a Shenzhen assembly plant to other components sourced from Germany, Japan and Korea to produce a smartphone which is then shipped back across the Pacific to be sold to a US consumer.

US-China trade war: not about trade, not about Trump. Here’s what it is about

It might sound like a cumbersome process. But in recent decades the development of integrated supply chains has allowed countries around the world to concentrate on economic activities in which each holds a comparative advantage. In short, global supply chains mean countries can focus on what they do best. The result has been marked increases in productivity, widespread economic growth and big improvements in material living standards around the world.

By launching a trade war that threatens to disrupt these supply chains, Trump would in effect be attempting to roll back the tide of globalisation that has propelled global economic growth.

Although some countries would fare better than others in the conflict, emerging as winners in relative terms, the resulting slowdown in global trade and investment would clearly damage overall world economic growth, and could even lead to a contraction in the world economy as a whole.

WATCH: Is trade war hurting US steel business?

The optimists hope the US president is bluffing, and that he intends to fight no more than a phoney war before settling for a showpiece settlement, as he did with North Korea.

In the pessimists’ view, Trump regards international trade as a zero-sum game, which for too long the US has been losing. To Trump, if tariffs inflict losses on other countries, the US will be the winner.

The coming weeks and months will determine which version is correct (and it is possible the US president himself does not know). In the meantime, however, the damage already done to trust in the global trade regime and to confidence in international investment suggests that the global economy as a whole is likely to be the big loser. ■

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staffer who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 20 years