The Flower Boat Girl tells the story of Cheng Yat Sou, who rose from sexual slavery to pirate royalty

- Writer and cartoonist Larry Feign’s new novel, The Flower Boat Girl, tells the stranger-than-fiction story of the pirate queen, punctuated by ripe Cantonese profanity

- But for all her achievements, she was largely written out of history because of her gender and the fact she was an Asian pirate

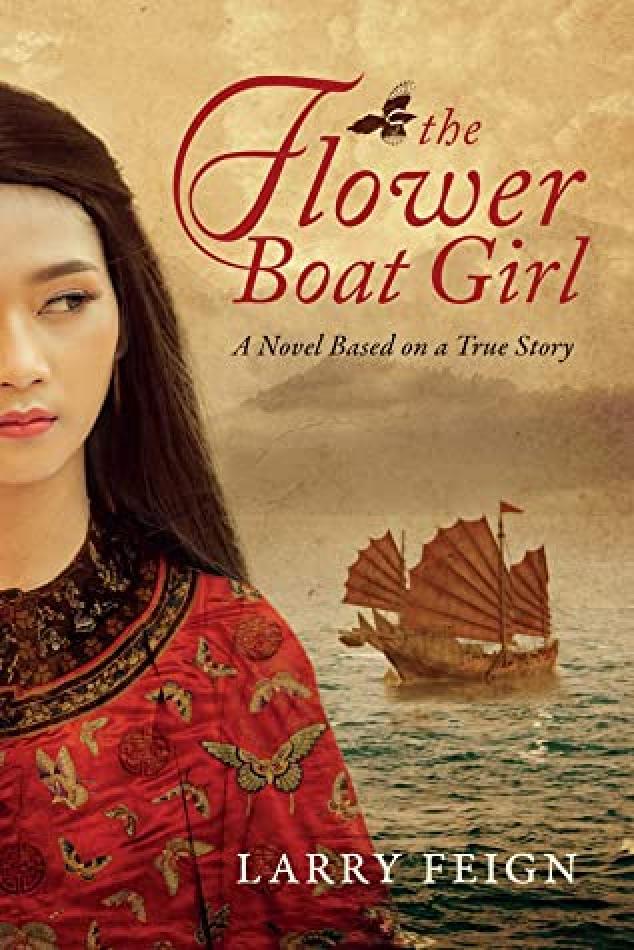

The Flower Boat Girl

by Larry Feign

Top Floor Books

Two million words and eight years after he had started researching and writing about the most successful pirate in the world, Hong Kong-based American cartoonist and writer Larry Feign binned everything he’d created. Telling the story as an outsider looking in just wasn’t working. But he knew what had to be done. He started again in first person, realising immediately, “Ah, this is natural.”

The Flower Boat Girl – a novel based on a true story, as it says on the cover –is the result. His first in the genre, about pirate queen Cheng Yat Sou (1775-1844), it was his “mission” to write it, he says. But 13 years after he had first heard about her – from a family friend in Tai O whose grandmother used to sing folk songs about a rebel “lady pirate” – a series of scary, other-worldly experiences at a Tin Hau temple in the old fishing village left him shaken. Certain Cheng would have worshipped at the shrine to the god of seafarers, he wondered whether to publish the book after hearing a spectral female voice remonstrating with him during his visits.

Readers who enjoy a swashbuckling yarn will be glad Feign persisted in disinterring Cheng Yat Sou – carefully. Unable to produce a biography because of the gaps in knowledge about her life, he has, however, painstakingly connected many of the dots, adding colour where hues had faded to grey. For help, he turned to experts on 19th century Chinese pirates, among them Robert Antony, formerly of the University of Macau, and Dian Murray, from whom he received copies of otherwise inaccessible historical documents.

Hongkongers with long memories will remember Feign’s previous alter ego, also a strong Chinese woman. For eight years up to 1995, the South China Morning Post chronicled The World of Lily Wong, revived by British newspaper The Independent for a limited period in the lead-up to Hong Kong’s handover to China, in 1997. In addition to his sometimes controversial cartoon strip, Feign has published 23 books, among them five children’s titles.

The Flower Boat Girl’s pacy dialogue hints at the years he has spent honing verbal thrusts and parries. He also convincingly renders Cheng’s stranger-than-fiction trajectory to pirate royalty, punctuated by ripe Cantonese profanity. Were her story reduced to bullet points, they would include that she was born in the Pearl River Delta district of Sun-wui (modern Xinhui) and sold into sexual slavery as a lowly Tanka boat girl.

Her life on the high seas began after she was kidnapped in a village raid by pirates who prowled the south China coast. She assumed the helm by marrying their leader, Cheng Yat, himself descended from pirates. However, becoming the “captain’s wife”, after which she was known as Cheng Yat Sou, was far from enough. Ambition, intelligence and a desire for freedom pushed her to greater heights.

Describing his as a feminist novel, Feign explains how Cheng Yat Sou elbowed her way to commanding a confederation of 1,800 ships and 80,000 pirates, setting up a protection scheme that would lead to cooperation among the various fleets to earn shared revenues.

But for all her achievements, she was more or less written out of history for two main reasons: her gender and the fact she was an Asian pirate. By comparison, he points out, “Blackbeard, considered the most powerful pirate in history, had 12 ships and 500 men under his command.”