- More women are being threatened with the release of their intimate photos or videos, as cases peak during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Survivors in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia are struggling to have this content removed from online platforms, where hundreds of entries portraying sexual violence can be found

This is the first in a series of stories on image-based abuse supported by the Judith Neilson Institute’s Asian Stories project, in collaboration with The Korea Times, Indonesia’s Tempo magazine, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, and Manila-based ABS-CBN. Cat Thomas, Yon Sineat and Kong Meta contributed reporting. The piece contains descriptions of a sexual nature. This story has been made freely available as a public service to our readers. Please consider supporting SCMP’s journalism by subscribing.

Laura*, an office worker from Hong Kong, recently found out that some of her most private moments had been circulating on the internet – for about a decade.

Thousands have been able to pry into her personal life through the screens of computers, mobile phones, and tablets.

“I was shocked,” she said. “To put it simply, an admirer found a video on a porn website and I was in the video. It was filmed secretly.”

“The film is 10 years old and yet he could still recognise me,” she said, referring to a work colleague who had been courting her for months. At first, he seemed concerned about her well-being, but his manner changed when Laura said she was not interested in a relationship with him.

“When I rejected him, he called me a slut,” she said. “He tried to blackmail me, to force me to be with him.”

Laura said he had threatened to leak the video on public forums and in a work WhatsApp group. At one point, he said he might even force her to have sex with him without using contraception. “He was out of control,” she said.

His threats have waned in recent months, but her fear remains.

[Part Two] Abuse and anger: inside the online groups spreading stolen, sexual images of women and children

[Part Three] For lust and money: when online sexual encounters end in despair and death

Our examination also found hundreds of videos on pornography websites labelled as featuring young girls or coerced women, with some even directly referencing rape.

While experts warn of the severe consequences of “normalising non-consent”, survivors are struggling to get their photos and videos removed from online platforms, with many Asian countries still lacking laws and adequate police procedures to tackle the issue.

MORE CONNECTED, MORE AT RISK

Behind closed doors, many turned to screens for work, relaxation, and intimacy in all its forms. Chatting apps, social media networks, and dating websites often became their only connection to the world and other people. But while access to technology helped bring families, friends and colleagues together, it also allowed for the growth of image-based sexual abuse.

The Asia-Pacific region has the world’s largest number of internet users, most of whom are men, according to the latest statistics. As of January, China and India topped the list with about 989 million and 624 million internet users respectively.

Maleka Banu, general secretary of women’s rights group Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, said the fact that more people had access to mobile phones and the internet had led to an increase in online sexual abuse across Asia.

It’s now “easier to target [women] online without any risks”, Banu said, adding that the potential humiliation faced by survivors was greater in virtual spaces – an image can go viral with a click and be seen by millions.

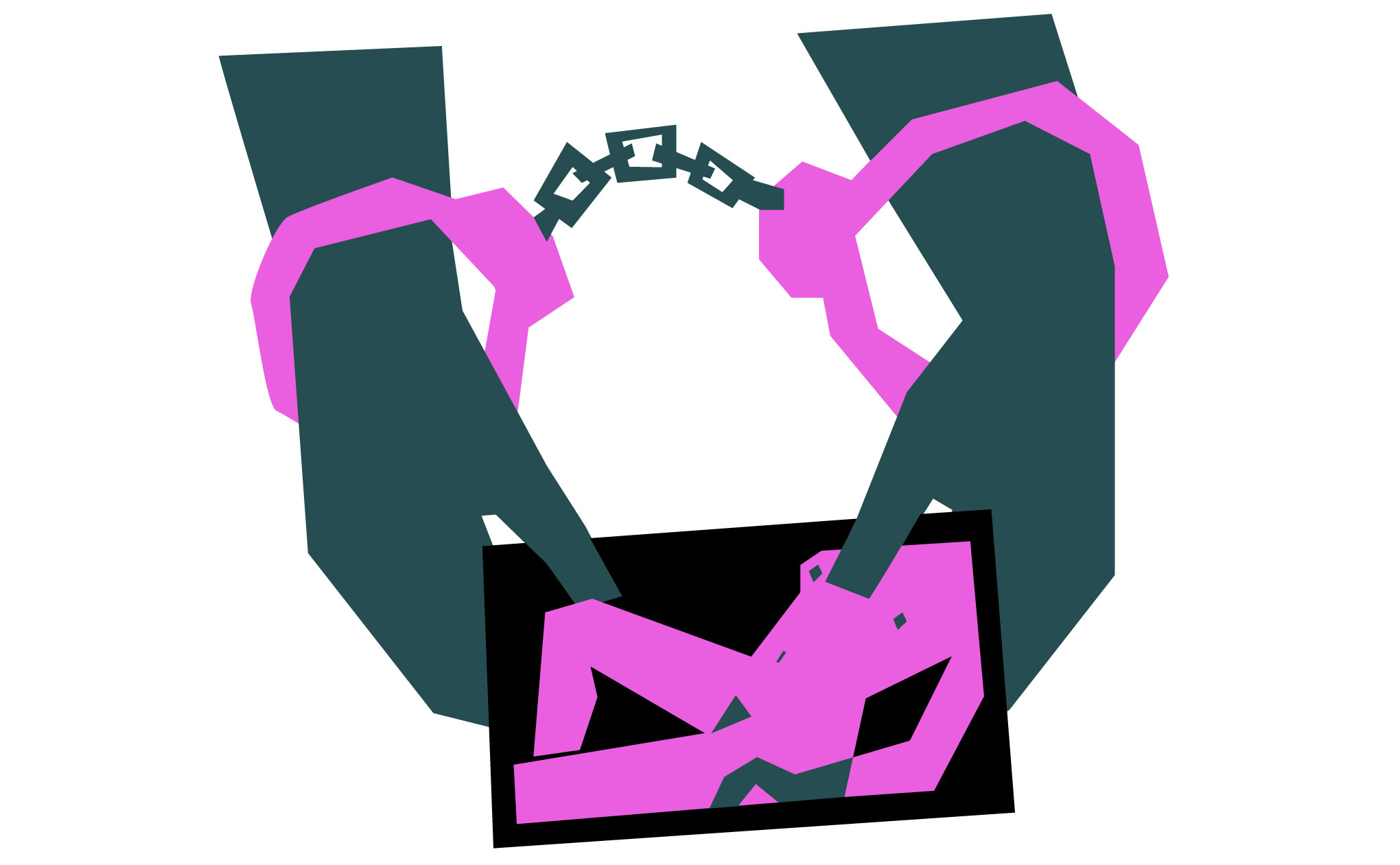

Image-based sexual abuse is defined by experts as non-consensually taking, sharing or threatening to distribute nude or sexually explicit photos and videos. This includes filming sexual acts; taking a picture under another person’s clothing; filming in changing rooms; and uploading intimate images to public online platforms.

It’s now easier to target women online without any risks

From Hong Kong to Britain, advocates and statistics indicate that most of those who suffer image-based abuse are women. Former partners and acquaintances are often the main perpetrators, using intimate images to seek sex, reunion, or simply to damage the survivor’s reputation. This form of abuse has become known as revenge pornography – but experts say the term should be avoided as it fails to highlight the perpetrators’ full range of motivations and the impact on survivors.

Online sextortion is another common form of coercion, usually to obtain money or more images from victims. Men are often the targets of sextortion cases involving criminal groups.

An international study conducted by four scholars – including Anastasia Powell, lecturer in justice and legal studies at RMIT University in Australia, and Adrian J. Scott, senior lecturer in psychology at the Goldsmiths, University of London – found that one in three people in Australia, New Zealand, and Britain had experienced some form of image-based sexual abuse.

The research, published last year, also suggested that women tended to report greater negative impacts than men. Most survivors were targeted by people they knew, while sexually diverse groups and members of ethnic minorities seemed to experience higher victimisation rates. Previous studies had also shown higher rates of sexual violence and harassment against groups such as transgender, intersex and gender-queer people.

“There is little doubt that nude and sexual images are increasingly being used to coerce, threaten and abuse victims,” the study said. “These harms extend well beyond the vengeful actions of a jilted lover and cross over into perpetration of domestic and sexual violence, stalking, bullying and sexual harassment.”

‘DEMAND FOR NON-CONSENSUAL MATERIAL’

Visual content taken or shared without the consent of the subject can easily be found on multiple platforms, including social media and chat apps such as Instagram and Telegram. On pornography websites, these images are interspersed with professionally made videos as well as amateur films that were shot and distributed consensually. With the lines between fake and real often blurred, consensual and non-consensual content is then posted under a range of categories including those that suggest blackmail, incest and gang rape.

XVideos has been described as the most-visited adult entertainment website, and one of the 10 most popular websites in the world; its 2 billion or so daily global impressions surpass the likes of Netflix or Amazon. Content labelled as featuring young girls is common, despite the site warning that uploading, viewing or possessing sexually explicit imagery of anyone under 18 years of age is illegal.

In a recent search, five of the first 15 videos on the XVideos homepage had titles mentioning “teens” and “schoolgirls”. That does not necessarily mean those involved in the videos were underaged, but there was no indication whether they were in fact adults and if there was consent. One that involved “two schoolgirls”, according to the title, had been seen by more than 55,400 people.

This Week in Asia found more than 10 videos that seemed to portray coerced or unconscious women, and the platform displayed hundreds of entries under the label “rapeing”. Such misspellings and code names, experts say, are a common attempt to avoid scrutiny for a piece of content.

A 10-minute sex video – which seemed to have been shot in India, and had more than 11 million views – featured a seemingly unconscious woman on a bed. “Why are all these women just lying there like they’re dead?” read one comment, referring to the video and other similar ones on the same page. A different commenter said the woman appeared to have been drugged, while another wrote: “People are commenting on how she looks dead or she’s sleeping but we gonna ignore how she looks kind of young?”

A separate video showed a woman, a plastic bag covering half her face, who did not react even after a man slapped her breasts. In yet another, a user wrote: “She is unconscious … this rape case must be reported to police.”

Another search brought up a seemingly amateur sex video that showed a naked girl surrounded by three young men. At one point she tried to reach out to the camera; the boys were laughing and posing, while she seemed to be in pain.

XVideos – which is owned by a company based in the Czech Republic – did not respond to repeated requests for comment, including questions about non-consensual footage and the screening mechanisms in place, that were sent through their website.

Clare McGlynn QC, professor of law at Durham University in Britain, said it was hard to say what proportion non-consensual images represented within the pornography industry, and how much money was involved in it – but what was clear “is our demand for non-consensual material, and this is deeply concerning”.

“We do know, from any view of the mainstream online porn companies, that there is a considerable amount of non-consensual material available,” she said. “This material is normalising non-consent.”

[Porn websites] are not using their own systems to prevent unlawful material being uploaded

In April, she co-authored a report in The British Journal of Criminology that analysed video titles on the main pages of Britain’s three most popular pornography websites – Pornhub, Xhamster and XVideos. The study – which drew on the largest research sample of online pornographic content to date, a total data set of over 150,000 titles – found that one in every eight titles shown to first-time users on the first page of these sites described sexual activity that constituted sexual violence, such as rape and upskirting.

“Our findings raise serious questions about the extent of criminal material easily and freely available on mainstream pornography websites and the efficacy of current regulatory mechanisms,” the authors of the study said.

The report found that “teen” was the most frequently occurring word in the entire data set, as well as the sample coded as describing sexual violence. The second most common category was that of physical aggression and sexual assault.

After coding, there were close to 3,000 titles with unique video identifiers constituting descriptions of image-based sexual abuse. These had a predominant focus on voyeurism, both explicitly and through more implicit terms such as hidden or “spy” cameras.

In December, Pornhub announced new measures to curb images of abuse on the site, as well as non-consensual and underaged activity, including a ban on unverified users uploading material. The move came after a New York Times report that accused the site of publishing child-abuse and rape-related videos.

More than 9 million videos are believed to have been removed as a result of the new policy, while that month both Mastercard and Visa said they had prohibited the use of their cards on the site.

A spokesman for Pornhub told This Week in Asia that if someone reached out to say a piece of content was non-consensual, it would be removed for review with no questions asked. “On average, a piece of content would be removed in a matter of hours. The process is quite simple, as we have a content removal request form linked on every page,” he said.

According to Pornhub’s transparency report, 653,465 pieces of content were taken down last year for possibly infringing guidelines, including videos depicting minors and non-consensual content.

However, some of these videos quickly emerged on other mainstream and underground websites.

McGlynn said porn platforms must be held accountable to a greater extent. “They are not taking down material fast enough when requested. And they are not using their own systems to prevent unlawful material being uploaded. Greater regulation of the companies is required.”

Laura from Hong Kong – who was filmed having sex without her permission – knows this too well. She tried to contact the pornography website to remove the video, but her attempts have failed.

“I realised that if you want to report it, maybe you shouldn’t do it alone,” she said, noting that it seemed a survivor did not have “the power or authority to remove the video completely from the platform” – though she argued this is something that ought to change.

“When it has been reported by the victims themselves, I hope [the video or images] can be taken off from the streaming platform instantly,” Laura said.

SECONDARY TRAUMA

Many countries do not have consolidated statistics on image based-abuse and lack official support networks, with the responsibility often falling to advocacy and support groups.

In Britain, Sophie Mortimer, manager of the government-funded Revenge Porn Hotline, said the number of adults seeking support for intimate image abuse almost doubled last year to 3,146 cases. More than 400 of the survivors were based outside the country.

Mortimer added that demographic data was scarce due to the reluctance of traumatised clients to disclose information that could potentially identify them. However, she said 62 per cent of the hotline’s overall clients were female, while when it came to sextortion specifically, 73 per cent of clients were male.

In Hong Kong, a police spokesperson told This Week in Asia the force did not keep specific statistics on image-based abuse. “Such cases may fall into broader categories, such as criminal intimidation or blackmail,” she said.

Advocates with the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women – a charity based in the city – said they had noticed an increasing number of queries last year, as the Covid-19 pandemic hit the city. The group handled 133 cases related to image-based sexual abuse, more than three times the figure in 2019.

But McGlynn from Durham University noted that official statistics were “only ever the tip of the iceberg. Few people report these crimes and even fewer cases get taken forward.”

Some don’t know where to turn, while others lack support to take their cases forward.

Hsiao Shan Cheng from the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation in Taiwan said the majority of the cases reported to their hotline involved women younger than 25, who often faced pressure from their parents. “Most of the time [they] will tell them: ‘Don’t tell anyone, don’t try to press charges. Pretend it never happened.’”

Many also fear facing additional threats as well as being further exposed during court proceedings.

Laura, in Hong Kong, is one of the survivors who decided not to report their case to the authorities.

She considered sending a warning letter through a lawyer to the ex-partner whom she believes filmed the video that eventually emerged on a pornography website. But she feared that going deeper would only bring her more pain.

Legal action would be costly and unlikely to succeed, and there was still more uncertainty, Laura said. “I don’t know what he will do to me if he receives the warning letter,” she said, noting that the two had not been in touch since they were at university.

Their relationship ended acrimoniously, but she does not know why he decided to shoot and upload the video. “Pretty sure it was not for money,” she said.

Despite the challenges she has faced on her own, Laura is adamant that she will not take the case to the authorities. She said she doubted the “police’s professionalism”, arguing that the procedures often do not take survivors’ mental health into account.

“I bet every victim would want those who threatened them, disseminated the film or shot the film to be caught and jailed,” Laura said. But “when reporting it, going through the judicial process and waiting for the verdict, you need to watch the video again countless times, or go into details about it”, she said, adding that this would lead to her suffering “secondary harm”.

“I’m also worried that it may bring up details I don’t wish to remember.”

CONTINUOUS THREATS

Survivors in multiple jurisdictions who decided to report their cases said they had encountered issues such as ill-prepared officers, interviews conducted in inappropriate circumstances, and a lack of support.

After Crystal*, a 20-year-old student from Hong Kong, broke up with her boyfriend last year, she faced a barrage of threats from him. One came in form of a link to a cloud-based folder containing intimate images of her, followed by text messages saying “I have got everything ready” and “I will have fun with them slowly”.

She decided to report the case to the police; the perpetrator was eventually invited by the authorities to assist in the investigation, but he was not arrested.

“I expected that making a report could help stop this kind of threat, but not only [did it not help], it also sent my ex-boyfriend a signal that what he did is allowed by the law,” Crystal said.

She was also told that the evidence she had, such as the text messages from her ex-boyfriend, was too weak for him to be prosecuted for criminal intimidation.

The photographs of her are still in the folder – and she does not know who else has access to it.

“I have become very unwilling to meet people following the incident, because I don’t know if these images have been uploaded and viewed online,” she said. “I feel like people stare at me because of these images when I am in public.”

Crystal has been so much under stress that she even considered suicide. “The scariest part is knowing that I might have to live with this fear for the rest of my life,” she said. “I have thought of ending my life so the incident can be over.”

Laura also said her ordeal had affected her personal life. While the news that private images of her were circulating online was still sinking in, she had to face several instances of harassment from her admirer who discovered the video.

I have thought of ending my life so the incident can be over

“He would wait for me downstairs outside where I live, he kept calling and asking me to meet to threaten me,” Laura said. Over the course of six months, the blackmailer repeatedly sent the video to her boyfriend at the time.

“This gave me second thoughts about pursuing a relationship with another man,” she said. “I didn’t realise my emotional instability until I met other men or started rebuilding intimacy. This is something that may carry on in me, [although] I may seem to be able to function day to day.”

Laura said she often cried during intimate moments, reactions that have puzzled all of her ex-boyfriends. “I refused to tell them why, all I could say to them was ‘I can’t’”.

Linda S.Y. Wong, executive director of the Hong Kong-based Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women, said Laura’s and Crystal’s experiences were not uncommon.

“Image-based sexual abuse cases that involve the element of threats often cause extended trauma to victims, with symptoms like anxiety and flashbacks,” she said.

In response to calls from survivors and advocates, the Hong Kong government in March gazetted an amendment to the Crimes Ordinance aimed at preventing non-consensual intimate recordings, including upskirting and taking photographs down a person’s top; voyeurism; and the publication of or threat to publish intimate photos or videos without permission.

Offenders will be punished with a maximum jail term of five years – and some may go on the sex offenders register. The amendment has been introduced to the city’s Legislative Council and the process is likely to be completed this year.

While rights groups have hailed the move, which they say recognises the harm done to survivors, they point out there is still room for improvement when it comes to preserving the anonymity of those who have suffered abuse; court protective measures; and the inclusion of deepfake and superimposed images.

“We think the definition of intimate images can be extended to cover the behaviours which involve non-consensually editing someone’s face onto intimate or pornographic images produced elsewhere,” Wong said.

She also said there were concerns that the proposed legislation did not provide a sufficient mandate for courts to order the removal of images.

FLAWED SYSTEMS

While some countries and regions have only recently started working on improving regulations and introducing specific laws to tackle cases of image-based abuse, others have yet to enact any.

In Taiwan, experts and advocates say survivors of intimate image abuse have been let down by a flawed system and a society that has a poor understanding of how such cases arise. Until a dedicated law is passed, they say, targets as well as the police and the courts are left struggling to deal with cases using existing legislation.

June*, a 41-year-old teacher in Taiwan, was in a committed relationship with her then-boyfriend, Max*, last year. The relationship turned sour when Max began drinking heavily and one night became violent.

“He didn’t like that I broke up with him,” June said. Instead of accepting it was over, he “started a campaign of daily calling, messages, threatening suicide on Facebook”, and began stalking her at her home and workplace. At one point he threw himself repeatedly against her front door, terrifying her young daughter.

A few days after one such incident, June received a call from a friend of Max’s, a woman whom she had never met, who told her Max had sent an unsolicited nude photo of her to another male friend.

“It sounds like a cliché, but it feels violating,” she said. “I won’t even say that I feel stupid, because it was in the context of a relationship with people trusting each other.”

I'm sure he has a copy [of my picture] somewhere. What if the next time he gets drunk he does it again?

She filed a report at her local police station in late October, an experience she described as awkward but efficient despite it taking five hours. Her interview was held in the general office area, and while June was pleasantly surprised at how sensitive the male officer was, she said privacy was sorely lacking.

“I didn’t appreciate sitting in front of all these people walking by with loud blaring radios coming off their shift and shouting at each other about what dinner box to order while I was trying to relate intimate details,” she said. “It was highly unpleasant.”

Max’s lawyer unsuccessfully tried to get June to drop the criminal case and accept civil charges instead, offering a lump sum of money or a public apology. “I definitely don’t want money from this man. That would make it more disgusting somehow,” she said.

The case is still in progress and June is haunted by the possible consequences of the violation of her privacy, including that a background check for a new job might turn up a nude picture of her.

“I’m sure he has a copy somewhere. What if the next time he gets drunk he does it again?” she asked. “I have done nothing wrong and yet there is an inappropriate picture that exists in the public realm. I don’t like that idea at all. For my kids to maybe find it, even less,” June said. “They don’t have free access to the internet, but when they are older, I will be certain that they learn from this.”

Ten of these images were shared on a Telegram group with 726 members, and her ex-partner also uploaded photos on Tumblr, in which she was fully clothed, in a folder labelled “prostitute”. Videos of her were also circulated without her consent on pornography websites such as Xhamster.

“With the police, the process was a rather difficult and emotionally draining one for my client,” Teeruvarasu said, adding that she was assigned to a male investigating officer, which “by default made it harder for her to divulge intimate details”.

He added that the police were also at times slow to act. “When my client requested an update days later, she was informed that no further action would be taken in regards to her complaint,” Teeruvarasu said, explaining that he then had to approach the investigating officer’s superior. “Upon me doing so, the very next day her former partner was arrested and remanded to facilitate investigation.”

After the investigation turned up sufficient evidence, the woman’s ex-partner eventually pleaded guilty to possessing and distributing pornographic and obscene material, and was sentenced to a fine of 3,000 ringgit (US$725).

Teeruvarasu points out that though the punishment may seem insufficient, “the principles of sentencing and justice must be taken into account, irrelevant of the crime. From my understanding, it was his first offence and as such, this is common.”

The case also allowed him to see the cracks in the support system for survivors, including the “inadequate assistance given to victims before and after lodging a complaint”. “Upon being notified that hers was a complaint of a sexual nature, she should have at least been referred to the D11 unit [Sexual and Child Investigation Division], who would have been more equipped to handle her complaint.”

Yet the greatest challenge was posed by the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), Teeruvarasu said. The regulator – which can order users, subscribers, or content providers to take down prohibited content – blocked 2,921 pornographic websites from September 2018 to the end of last year.

But Teeruvarasu said they only responded to his client’s complaint after multiple letters had been sent. “When they did get back to her, they instructed her to contact Telegram to remove her intimate images, something she had already done and received no response. [The commission] was of no help during this entire ordeal.”

Despite all efforts, and having secured a conviction, her non-consensual images remain online.

The commission said in an emailed response that it did not have comments on this issue.

Nicole Jo Pereira, a community development executive with the Make It Right Movement at Brickfields Asia College in Malaysia, said while the authorities took swift action regarding seditious remarks or fake news online that affected the nation’s image, “there appears to be a delayed response when presented with a complaint of dissemination of intimate images online or sextortion”.

She suggested that the MCMC launch a task force focused on handling complaints related to the sharing of pornographic material, and pointed out there was “a real need” to introduce anti-stalking laws and table the country’s long-delayed sexual harassment bill.

“No one, be it man, woman or child, should ever be made to feel as though they have lost all ownership and dignity over something so private and personal [as] their own bodies,” Pereira said.

While laws should protect survivors of image-based abuse, in some cases they not only fail to do so – they even backfire and cause harm.

Although Pakistan has a law that specifically criminalises non-consensual distribution of video or photography “in a manner that harms a person”, advocates say survivors have grappled with different forms of retaliation after taking their cases to the police. Those whose images are leaked also face enhanced risks in a country where honour killings continue to take place.

In Indonesia, some women whose intimate images have been distributed without their consent have themselves been charged under the country’s draconian anti-pornography law. Rights groups have called on the government to push for a revision of policies that have the potential to criminalise survivors, and to introduce further protections for those who face cyber violence.

But even in nations where survivors don’t face similar risks, they often shoulder the blame.

Channary*, 38, from Cambodia, was in a two-year relationship during which her partner often asked to take nude photos of themselves.

After they broke up, and her former partner learned she had become engaged to another man, he started threatening to send the pictures to her future husband as well as uploading them on Facebook and tagging her relatives and friends.

If I wasn't brave enough to threaten him back, he would never stop

Following months of threats, she mustered the courage to tell her family and her fiancé what was happening. Having gained the support of her loved ones, Channary then told her former partner she was planning to file a police complaint.

“I think if I wasn’t brave enough to threaten him back, he would never stop,” she said.

But Channary never went to the police, and spoke to few people about the incident. “Besides [talking to] my family and close friends, I did not share this incident with anyone else, because Cambodian culture is so conservative. They will blame me for having sex with that guy and letting him take a picture of me,” she said.

Rachana Bunn, executive director of the women’s rights group Klahaan, said few survivors came forward because of “the cultural belief that Khmer women should remain chaste and virginal before marriage”.

Although Cambodia’s Ministry of Interior has established a national anti-cyber crime unit to handle such cases, Bunn said the existing laws were insufficient, and pointed out that the general public – especially young women in remote areas – were either not aware of such mechanisms or did not have the means to approach them.

“More fundamental, however, is the urgent need to change broader attitudes in Cambodian society that normalise the sharing of revenge porn, and serve to further vilify and stigmatise women,” she said. “These are young women who themselves are committing no crime, but are rather simply expressing their sexual autonomy with another consenting adult.”

Shailey Hingorani, head of research and advocacy for the Singapore-based non-profit Aware, said many survivors of technology-facilitated sexual violence often received victim-blaming responses, even from well-intentioned relatives, colleagues and officials.

“It is sadly not uncommon for survivors to be asked why they sent revealing images to their partners in the first place, or used such-and-such app or social media platform,” she said.

Kuhan Manokaran, a lawyer in Malaysia, also said it had been challenging to help clients overcome embarrassment and stigma. “In Asian cultures, sex is considered a taboo subject and seldom discussed in public … Some even feel silly or foolish for having trusted the perpetrator,” he said.

Experts and advocates across multiple countries said education and awareness were the most important steps to prevent image-based abuse from taking place, along with setting up support mechanisms for survivors.

“All these elements of support, including your doctor, the counsellor, the police, the helpline … they all need to be placed around the same table,” said Folami Prehaye, founder of the Britain-based support group VOIC, or Victims of Image Crimes.

“This is a form of abuse. Whether it’s online or offline, it’s still sexual abuse … We very much live in this virtual world,” she said, noting that the possibility of adding perpetrators to a sexual offenders list could serve as a deterrent.

Laura, in Hong Kong, said she hoped more women realised they were not alone.

“No one would like a video or photo of them to be distributed without their consent. Some people like uploading it themselves and that is another story,” she said.

Laura has been able to overcome some of the distress from discovering that there was an intimate video of her online, and the blackmail threats. But she has not told her family or her partner.

“More or less he could guess that I experienced something unpleasant, but he kind of accepts my fears and is still willing to be with me,” she said.

Laura doesn’t know if she will ever cross paths with someone who has seen the video, and she still worries about her partner’s eventual reaction. She also doesn’t know if the blackmailer will resurface: there is this “fear that he will always have something in hand to threaten me with”.

She believes that the video remains online, a veiled threat that can be detonated through a screen with just one click.

“It’s a ticking bomb,” she said.

Yet Laura feels she has grown stronger, and demeaning comments no longer carry the same weight: “I am the victim here, then why am I the one being called a slut?”

*The names of survivors and people related to them have been changed to protect their identities

Credits Lead reporter and project coordinator: Raquel Carvalho Reporting team: Cat Thomas (Taiwan); Yon Sineat and Kong Meta (Cambodia) Graphic artist: Kaliz Lee Research for graphics: Cheryl Heng Copy editor: Hari Raj With support from: