India’s digital divide is hampering its mass Covid-19 vaccination campaign

- Millions of Indians do not have access to the internet or a smartphone, yet vaccine registration can only be done online through a government portal

- Other challenges include vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, people lacking identification documents, and the status of refugees such as Rohingya

This is pretty recent, however. In May, when New Delhi was recording over 25,000 cases and 500 deaths nearly every day, the shanties in Paharganj made sure the virus was kept out.

Jeevan Kumar, a 46 year-old labourer from the state of Bihar, was among those on guard. “We worked in shifts and patrolled the area so that no outsider could creep inside the slum with the virus. Little children would roam around the shanties asking everyone to mask up. With these efforts, we saved our slum from a major disaster.”

“People have lost their patience now and are venturing out without masks. If there is a time to vaccinate slums and other such potential hotspots, it is now,” Kumar told This Week in Asia.

But in the Paharganj slums, residents do not know anyone who has had a jab.

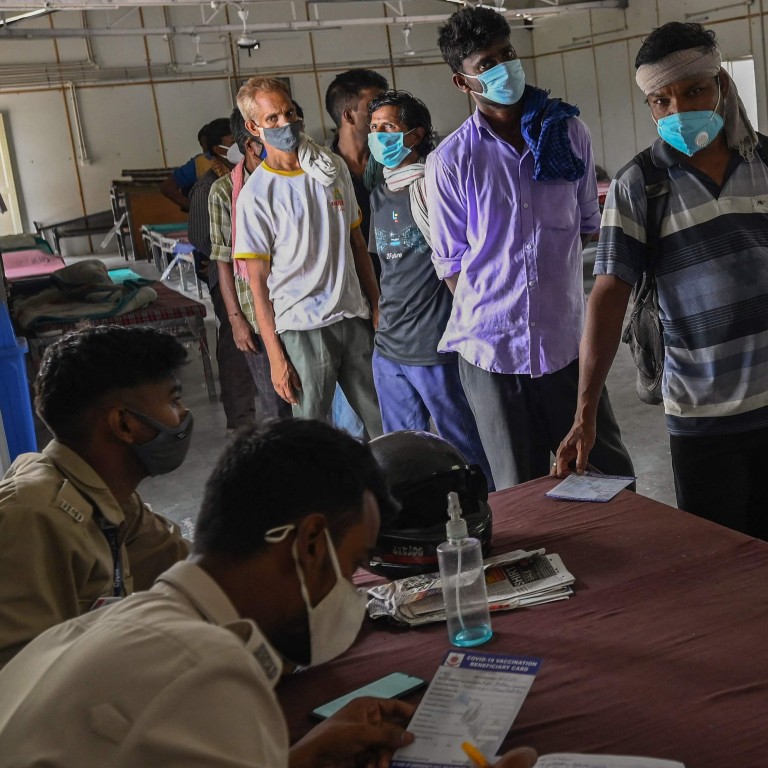

However, the campaign has faced a number of challenges, including vaccine shortages and logistical hurdles, meaning only 8 per cent of adults have been inoculated. Last week, just 4 million doses a day were administered, compared to over 9 million the day after vaccinations started.

Indian stores offer Covid-19 deals for vaccinated customers

The drive is also digital-only and citizens have to register on the government’s online portal CoWin and then receive a code via mobile phone.

This is impossible for many in a country where internet penetration is only 45 per cent, meaning there are about 624 million internet users among a population of 1.39 billion, according to DataReportal. Roughly 550 million still use feature phones which cannot access the CoWin portal.

This digital divide is even starker in places like slums where most people do not own mobile phones.

“If the government says everyone should get vaccinated, then why are we being left out?” Kumar asked.

“We do not want to die, or fall ill. Everyone in this country has a right to life; then why are these digital barriers there which prevent us from receiving vaccines?”

The Supreme Court of India has come out in support of people like Kumar, criticising the government’s vaccination policy and noting that “digital literacy in India is still far from perfect”.

The judges said that “exclusively relying on a digital portal for vaccinating a significant population of this country … [means the government] would be unable to meet its target of universal immunisation owing to such a digital divide”.

“It is the marginalised sections of the society who would bear the brunt of this accessibility barrier,” the court said, adding: “Wake up and smell the coffee.”

The government expects those without access to digital resources will be able to “take help from family, friends, and NGOs”, the court said.

NGOs helping out

Jan Pahal, a New Delhi NGO, has been trying to bridge the gap. With a team of nearly 100 volunteers and community leaders, the organisation is among those assisting migrant workers, street vendors and homeless people.

“Our volunteers are reaching out to people who either don’t know how to register for vaccines online or simply don’t own a mobile phone at all. In such cases, we register and book a slot on their behalf,” said Dharmedra Kumar, the secretary of Jan Pahal.

But in a country where many do not even have an identity document, the already complicated vaccination process can get even more difficult.

If the virus reaches the camp, it will engulf us all

“Our NGO runs 10 night shelters in Delhi and we have some people there who don’t possess any official documents at all. Without any papers, it would have been literally impossible for them to get vaccinated but somehow we requested the authorities and managed to get vaccines for them.”

NGOs like Jan Pahal concede they can only do so much.

“We are reaching out to as many underprivileged as possible. But with limited resources and reach, NGOs cannot be a substitute for the government,” he cautioned.

The refugee camps for Rohingyas in Delhi are a visible testament to this. Even though most inhabitants have United Nations sanctioned refugee cards, the migrant community is apparently not even in the race for receiving vaccines.

“No one has come to vaccinate us or told us how to get it,” said Saleem, a 40-year-old community leader.

“We even reached out to the UN but still no vaccines have been given to us. Nearly everyone here has some underlying medical conditions. If the virus reaches the camp, it will engulf us all.”

New Delhi camp blaze exposes plight of India’s Rohingya refugees

Last month, India’s health ministry released a new guideline to open vaccinations for people who do not have biometric ID cards called Aadhaar, allowing 11 documents including passports and election cards to be used instead.

The move was welcomed by the UNHCR, which called it “an opportunity for vulnerable groups including refugees to access vaccines”. But the ministry did not include UN refugee cards, which India does not recognise as it is not a signatory to the United Nations Refugee Convention of 1951.

There are about 1,500 registered Rohingya refugees in Delhi, and many more unregistered ones, but they are still considered to be in the country illegally.

Vaccine hesitancy

Meanwhile, hesitancy among many Indians to get vaccinated is also hampering the roll-out. Health workers have complained of facing stiff resistance while administering doses, particularly in rural areas. In one such instance, accredited social health worker Sarita Kumari and her team were prevented from setting up a vaccine camp and turned back by an entire village.

“It is mostly the women who hesitate the most. When we approach them, they make excuses or simply lock themselves inside,” Sarita said.

Rumours about jabs disrupting menstruation cycles and reducing fertility have contributed to fears among women, skewing vaccination rates in favour of men as a result. In almost every Indian state, more men are getting vaccinated than women – and the gap is widening further every day.

India’s Covid-19 widows: a tale of grit and resilience in the face of despair

Quashing such rumours and conspiracy theories is a tough order for health officials, particularly in India’s tribal-dominated districts that have recorded disproportionately lower vaccination rates than other regions.

“Some elements in our society have raised the untrue claim that the shots can cause infertility,” said Vidya Lakshmi, a retired gynaecologist. “We have to convince people, go door-to-door, and encourage women to shun hesitancy. And everyone from the government to civil society and NGOs need to come forward for this.”