Hong Kong’s inflation: nowhere as bad as other global cities but why are some still feeling the pain of higher prices, especially for food and transport?

- Hong Kong has escaped relatively unscathed even though the city relies on imports

- But many among the city’s underprivileged are feeling the effects of low but festering inflation

It is late afternoon near closing time and stall holders at a crowded Sheung Shui market are slashing prices. Single mum and dole recipient Amy Wong, 35, makes a beeline for the bargains to feed her family of three. In her purse is her daily budget of HK$150.

She pops into a butcher’s shop to buy a catty of pork for HK$29, then picks up a packet of buns for HK$25 which will do as breakfast for her children, aged four and nine. She then races to another shop to buy some bananas for HK$20 before getting a small bag of vegetables for HK$23 and then she rushes over to another stall to buy two trays of eggs for HK$40.

“The food costs less than HK$140 but it will be enough for making three meals which is the most important and fundamental thing for our family’s survival,” she said.

“But I can’t make soup as the ingredients will cost a lot more,” she lamented. “Life has become very difficult for us. I have no choice but to tighten my belt to feed my two children.”

Wong is among the city’s underprivileged feeling the effects of low but festering inflation, as life becomes more difficult for this group of residents battling a host of price rises on a range of goods, from food to electricity to looming increases in transport fares.

Ting Wong, 38, whose family of four migrated from Hong Kong to southwest London last summer, is among those finding it tough. She said her daily expenses, especially for groceries and utility bills, had ballooned by about 30 per cent over the past year.

She now scrutinises her spending carefully and keeps her eyes peeled for discounts and deals.

“I wish the government would provide more support, the richest people can afford higher taxes but not the working class,” said Wong, who runs a real estate agency in the British capital with her husband.

Britain’s inflation rate peaked at 11.1 per cent last October and had been falling until a surprise jump to 10.4 per cent in February, before easing again last month to 10.1 per cent.

Hong Kong’s inflation rate is far milder, at 1.7 per cent in March, down from the average rate of increase of 2.1 per cent in January and February.

So why has Hong Kong escaped relatively unscathed even though the city relies on imports from food to fuel?

Hong Kong out of global inflationary snare?

Hong Kong’s low-income families cut back on food as electricity rates increase

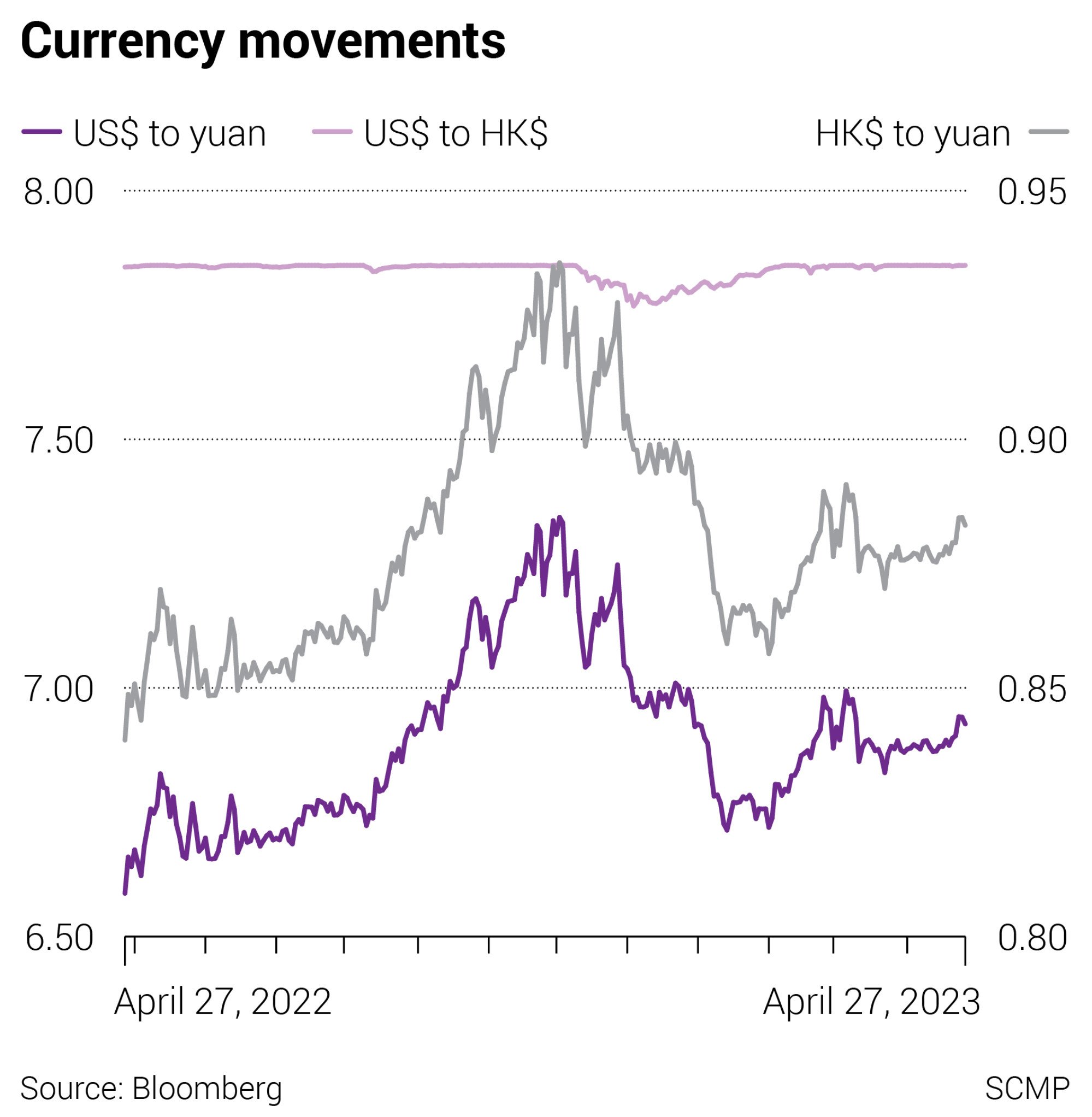

“Food supply from the mainland is stable. The weakened Chinese yuan is also favourable for Hong Kong as its currency is pegged with the US dollar. As the US dollar is getting stronger, we can buy mainland items at a relatively cheaper price with the Hong Kong dollar,” Lee said.

“Importing items from nearby countries with weaker currencies like Japan and Thailand is also cheaper in terms of the products and transport.”

The Hong Kong dollar appreciated by as much as 5.3 per cent against the yuan at one stage before gaining 4.7 per cent over the past year.

Lee added inflationary factors in the US and Europe were mainly caused by fuel price and logistics costs along with their food import structures. In the US, for example, transport costs make up 13 per cent of the basket of goods and services measured, or the consumer price index (CPI).

Housing makes up 32 per cent while energy costs account for 7.5 per cent and food comprises 14 per cent of the index.

In contrast, housing and food prices accounted for a larger share of the CPI in Hong Kong. Housing stands at 40 per cent while food, mostly imported from the mainland, accounts for 27 per cent. Other components of the index include electricity and gas, which account for 2.8 per cent of the overall weighting, and transport costs 6 per cent.

China’s consumer prices set to edge up amid reopening despite ‘puzzling’ fall

Economists said the weighting composition explained why Hong Kong’s inflation had remained low unlike what had happened in the West as housing prices had continued to drop in the past while overall food prices had remained low because of mainland imports.

“On top of the impacts of energy sources and import prices, countries other than the US are also affected by currency depreciation. With inadequate subsidies provided by their governments, their inflation impacts are more profound than Hong Kong’s,” Ng said.

Spiking inflation? Hong Kong businesses set to shift cost to consumers

He warned that Hong Kong could see a relatively rapid rise in inflation in the next two quarters as he predicted that in the coming months, the rate could reach higher than 2.5 per cent as energy and transport prices could spike with companies finally adjusting their costs.

“The weak economic performance and population outflows have weakened housing demand, leading to a decline in rents. But the fading subsidies from the government along with a recovery in housing rents will eventually affect residents,” Ng said.

Poor harder hit but middle class feel pinch too

For the poor, as food and transport makes up a larger proportion of their spending, they are consequently more acutely hit by price changes in these two categories of goods.

Wong, the single mother, felt the prices of daily necessities such as food and toiletries – one of the family’s biggest expenditures other than rent – had risen at least 30 per cent in Hong Kong since the border with the mainland fully reopened two months ago.

But official figures showed the overall inflation for food was 1.6 per cent in March year on year, which included a 2.8 per cent drop in basic food prices in March. A government spokesman attributed this to comparisons with a higher base figure a year ago when prices rose because of pandemic-induced supply disruptions.

Hong Kong grocery prices up 10 per cent from pre-Covid era, canned food most costly

According to a recent survey by the Consumer Council, grocery prices in three supermarket chains surged more than 10 per cent in the first quarter of 2023 from pre-pandemic levels in 2019, covering rice, edible oil, instant noodles and toilet paper.

Canned food is at least 30 per cent more expensive, with canned vegetables and fruits seeing the highest increase at 39 per cent. Canned soups and fish also recorded 35 per cent and 32.6 per cent increases, respectively.

The consumer watchdog urged people to shop around and compare prices to make smart purchases. It also compares prices of daily necessities such as food and drinks of various supermarkets on its website, an initiative called online price watch.

For Wong, avoiding buying unnecessary things and staying within her neighbourhood to save on transport and sourcing for occasional food donations from her church or social groups will be the other ways to cope.

“I haven’t bought any clothes for over a year and we seldom dine out. The most luxurious activity for us is to eat sushi at a restaurant once in a while,” the single mum said.

“I don’t buy snacks for my kids but they would like to have toys like the others. To compensate, I bring them out to play in the park to make them forget about toys. I really need to curb my desire to buy better food for my kids.”

The city’s underprivileged are not the only ones trying to cope from the soaring prices. The middle class is also feeling the pinch and scrambling for ways to counter the increases.

Agnes Leung, 39, who has a household income of about HK$100,000 a month, is among the few successfully countering inflation without compromising her living standards by taking full advantage of her job as an aircrew member.

Whenever she flies overseas, she seizes the chance to stock up on premium steak, pork and chicken from Europe and Australia, as well as organic fruits, vegetables, bread and yogurt from Japan, by filling an empty suitcase with 20kg of food for about HK$5,000 a month.

“The price of imported food in Hong Kong has gone up significantly, it’s about 30 per cent higher than buying directly from foreign places such as Europe or Japan. For example, I can buy 2kg of steak for just HK$100 in Australia. The price there is unbelievably cheap and it’s very good quality,” said Leung, who has a two-year-old daughter.

“I used to buy imported food in Hong Kong out of food safety concerns for my family, so I decided to directly stock up on food from foreign countries to save on expenses. Every time, I tow my luggage filled with meat and other food from abroad to my home.”

Kwun Tong replaces Sham Shui Po as poorest district in Hong Kong

For beautician Lily Cheung, 49, who lives in a public rental flat with two adult children, her monthly household income of HK$50,000 does not stretch as far these days, especially as she needs to support her 69-year-old mother with HK$10,000 per month in Guizhou province on the mainland.

“Things have become more expensive nowadays, by at least one-third. A set meal at a restaurant costs at least HK$70, up from HK$50 in the past. Our money has drastically depreciated,” she said.

Cheung avoids eating out, buys groceries at cheaper food markets rather than going to supermarkets, has reduced air conditioning use during the day, and cut down on shopping sprees and entertainment expenses.

“I now avoid cooking pricier food such as seafood and look for closing-time bargains like three sets of vegetables for HK$10,” she said.

More support needed

Many welfare advocates have called on the government to provide more support for the needy to ease their burden and cope with the price increases, including a review of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) payments.

Martin Chan Ka-shun, founder of social enterprise Amity, which distributes provisions to Sheung Shui’s needy, including those staying in subdivided cubicles and the elderly living alone, said his group had seen a 10 per cent rise in the number of people asking for food.

“Many residents complain about the soaring inflation which is making their life very difficult as they don’t have enough money to buy food and suffer undernutrition,” he said.

Chan urged the government to review the CSSA scheme to allow recipients to work for a limited number of hours to obtain extra financial support.

“This can help ease their financial burden while unleashing manpower into society to resolve the problem of worker shortages,” he said.

A spokesman for the Social Welfare Department said it had commissioned NGOs to operate a short-term citywide food assistance service to help those in need for up to eight weeks, and which could be extended for another eight.

It said the number of applications for the service slipped 5 per cent year on year to 20,910 in 2022, after a 13.1 per cent jump from 2020 to 2021.

“Service users with long-term welfare needs will be referred to appropriate services units for assistance,” the spokesman said.

“The Social Welfare Department will keep in view the economic situation and review the operation of the food assistance service from time to time so as to assist needy individuals and families.”