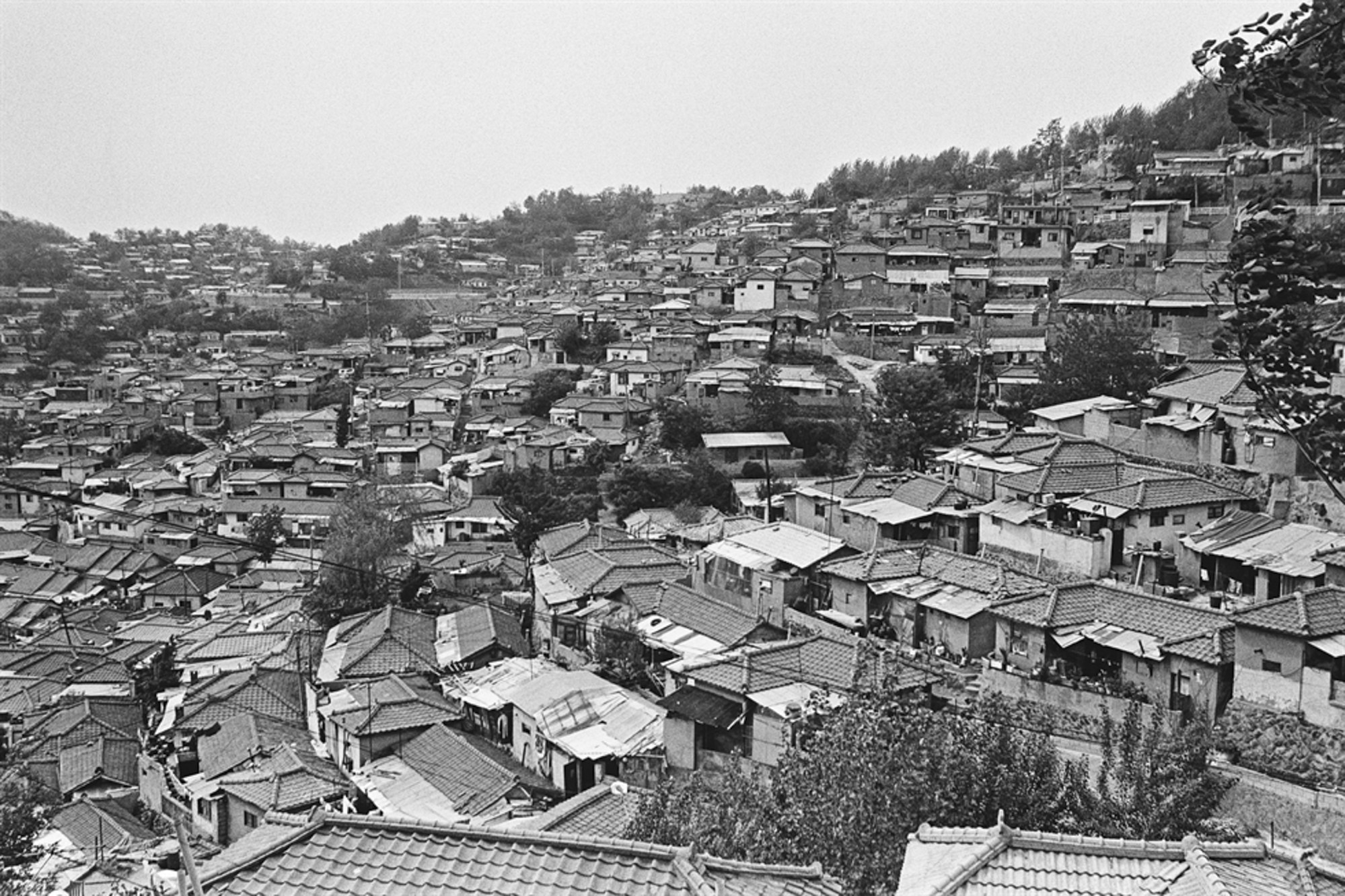

Old photos of South Korea’s ‘moon villages’ in Seoul reveal how people lived post-war before homogenous apartment complexes took over

- Now mostly torn down, Seoul’s ‘moon villages’ were largely home to urban poor, refugees from North Korea, and those from the countryside in search of jobs

- Through portraits of Seoul captured by documentarians, these neighbourhoods that disappeared into history over the last 40 years have gained new life

By Park Han-sol

A black-and-white snapshot captures the facade of a dilapidated shack in southern Seoul’s Apgujeong-dong neighbourhood, with a torn-out roof and walls that turn out to be nothing more than a mishmash of tarps and nailed wood boards of wildly varying sizes.

A few stranded household objects indicate that the tattered house was indeed occupied at one point: white garments hung on a clothesline far back, coal briquettes littered on one side and a handcart that was likely a source of income.

The obvious visual clash between the derelict shack and rows of identical high-rise apartments looming in the background would catch the eye of any passer-by.

That was exactly the case for student photographer Kim Jung-il in 1982.

Inspired by Eugene Atget, a French photographer who dedicated his craft to documenting the urban landscape of 19th-century Paris before its disappearance to modernisation, Kim went on a self-assigned mission to record Seoul’s post-war terrain that had been transforming before his very eyes.

So, what was Seoul like on the cusp of modernisation, early in its metamorphosis into a concrete jungle bursting with skyscrapers, hi-tech subways and a population of almost 10 million?

Post-war Hong Kong’s hard times and 1960s recovery shown in amazing photos

Through the portraits of the city captured by documentarians like Kim and Lim Chung-eui, its neighbourhoods that were razed and disappeared into history over the last 40 years have gained new life.

In their photographs, Seoul still manages to present itself as a forest of organically formed villages and twisted alleys that reveal an old way of living before homogeneous rows of apartment complexes took over.

“When I was taking photos of the parts of Seoul that were about to disappear, I knew that they would undergo transformation but never imagined it to be so profound and life-altering. We couldn’t have possibly envisioned the cityscape and skyline we see today,” Kim says.

Many of the places depicted in the two artists’ photographs come from different corners of daldongnae that once cluttered Seoul. Translated literally as “moon village”, these were communities that were built high up on mountainsides, thus allowing “a closer view” of the moon.

It’s a rather beguiling name given to the settlements formed as an inevitable by-product of economic hardship.

The villages were largely home to urban poor and refugees who poured in from North Korea following the country’s division in 1945 and the 1950-53 Korean war, as well as those from the countryside who flocked to the industrialising metropolis en masse from the 1960s in search of jobs.

The establishment of the Urban Redevelopment Act in 1976 provided administrative gateways for Seoul to carry out the so-called “downtown renewal projects” throughout the 1970s and 1980s. This period also coincided with the country’s bid to host the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Summer Olympics, which called for rapid, large-scale beautification schemes to project to the world a new cultural image of Korea beyond its war-torn past.

“The accelerated state-led redevelopment marked the beginning of Korea’s widespread land speculation and the consequent wealth divide,” Kim says.

“In Seoul, the elements that were once considered to be part of nature or one’s organically established residence … turned into objects of speculation with monetary value beyond the wildest imagination.”

Accordingly, most moon villages riddled with ageing houses and tattered shacks were razed, giving way to high-rise apartment complexes, car parks and public parks that make up most of the Seoul we know today.

Kim’s photographic representation of moon villages – most have become a thing of the past that now live only within the collective memory of older Seoulites – is fascinating.

As a student photographer attending Chung-Ang University, he chose some 40 sites to shoot that were designated as redevelopment districts in 1982 based on an article he read.

So, with his camera and a checklist in hand, he went on a personal artistic mission.

Taking cues from Atget, whose documentary photos of Paris were taken mostly at dawn and therefore showed no signs of life, Kim also decided to omit people from most of his images – but for a different reason.

“I thought it would be impudent of me to feature those residing in moon villages as mere props in my photos. I wanted to be careful when including them in the scene and avoid any semblance of so-called ‘poverty porn’,” says the 67-year-old.

His purpose of producing the series he later named “Landscape of Memory” (direct translation) had a few layers: objective yet aesthetic documentation of history that can serve as a concrete reminder of the moon villages’ existence.

Modern Korea has been great at “eliminating ‘outdated’ infrastructure without leaving a trace but has failed to document it properly”, Lim says.

That’s why the surviving photographic records that offer a glimpse into the country’s major transformation in the 20th century should be preserved for future generations, he says.

“Such materials need to be purchased by and maintained in state-level archives,” the 79-year-old says.

“After all, these records are more than just a part of the photographer’s personal project; they have immortalised a portion of the nation’s understudied history.”