East Asians have Toronto’s lowest coronavirus infection rate. But other Asian groups are suffering badly

- Toronto’s ethnic Chinese are weathering the epidemic well – yet it’s a much different story for Filipinos, South Asians and all other non-whites

- Wide disparities are also reflected according to income, with experts suggesting socio-economic factors like racism and poverty are likely at play, not genetics

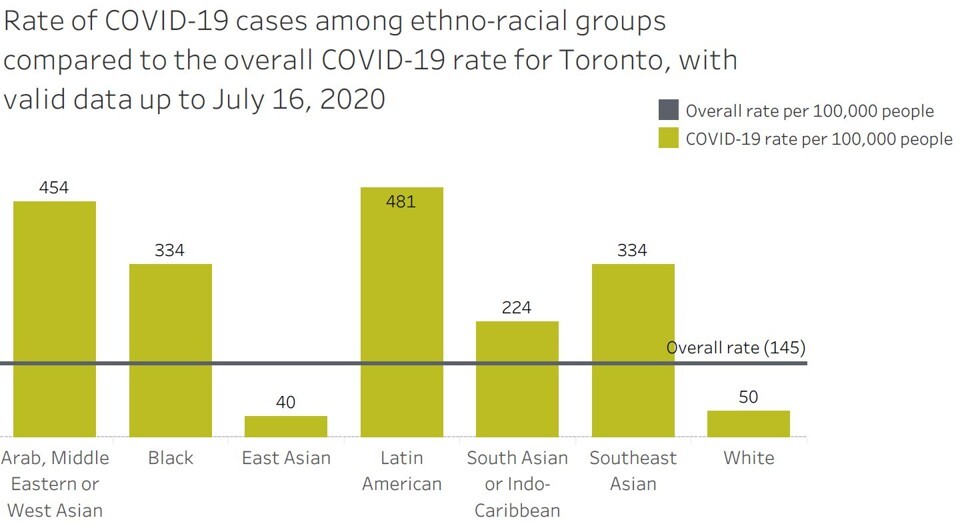

North American Covid-19 statistics that group Asian communities together have suggested they are experiencing relatively low infection rates – but new data out of Toronto indicates sharp differences among Chinese, Filipino and other Asian groups in the city.

Toronto’s large East Asian population, which overwhelmingly consists of ethnic Chinese, has the lowest rate of infection among all ethnicities.

But all other Asian groups have been hit hard. Southeast Asians, consisting mostly of ethnic Filipinos, have an infection rate more than eight times higher than that of East Asians; the rate for South Asian Torontonians is more than five times East Asians’.

In fact, all other non-white groups have infection rates that exceed the East Asian rate by huge margins.

White Torontonians, meanwhile, have an infection rate that is a more modest 25 per cent higher than East Asians’ – still much lower than the rate for the whole of this diverse city.

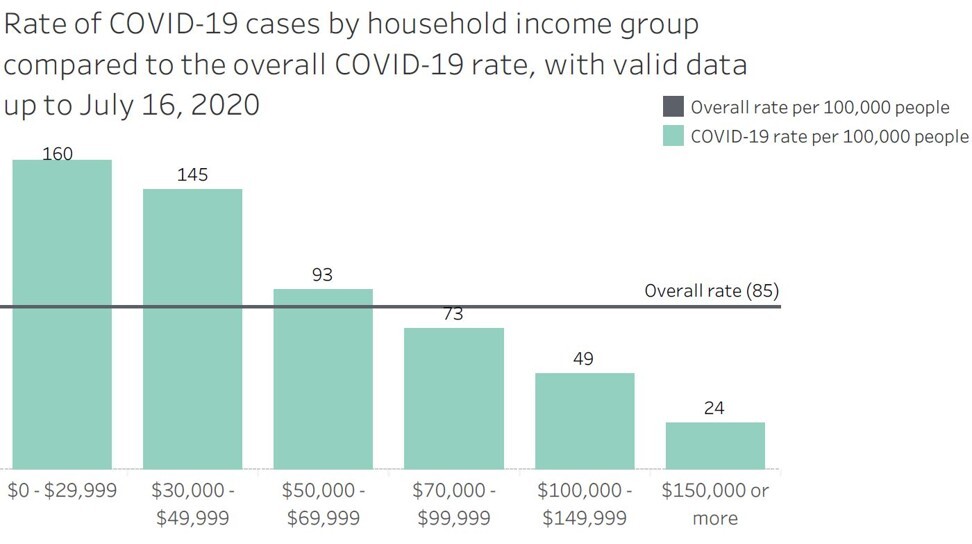

Experts suspect that a combination of racism, behaviour and circumstance explains the stark differences among various ethnicities. The fact that wide disparities are also reflected in income-based infection rates suggests that socio-economic reasons are at play, not genetics, they say.

Widespread and early mask usage among East Asians could be a factor, said Dr Jason Kindrachuk, a University of Manitoba virologist who is studying Covid-19.

Covid-19 rate in Canada’s most Chinese city isn’t what racists might expect

But teasing apart causality would take time. “Is it as straightforward as income? Could this relate back to earlier community acceptance of things like masks or social distancing?” he asked.

Either way, the data is crucial to identifying communities that bear the greatest burden in the pandemic, said Kindrachuk.

“In Canada we talk about being a multi-ethnicity community, but we’re starting to identify just how different our communities are, how different the vulnerabilities are … so we need to think about how we provide services to those most in need.”

The Toronto data likely reflected the higher risks of certain jobs, those that relied heavily on non-white employees and were ill-suited to social distancing, Kindrachuk said.

Canada’s care industry has high numbers of Filipino workers, for example, while its meat processing and seasonal agricultural sectors employ many foreign workers from Mexico.

As well as suggesting communities most at risk, the ethnic data also stood in sharp contrast to what Kindrachuk called “shocking” racist rhetoric about “the ‘China virus’ [and the] implicit targeting of the East Asian, the Chinese communities, as being to blame for the virus”.

What do some Chinese Canadians have against top doctor Theresa Tam?

Poverty, racism and risk in Toronto

The Toronto data, presented by the city’s Medical Officer of Health Dr Eileen de Villa last Thursday and current to July 16, split up East Asians, Southeast Asians and South Asians. West Asians were grouped with Arab and Middle East people.

Separate census figures show that Toronto’s East Asian population is 84 per cent Chinese; ethnic Filipinos similarly dominate the Southeast Asian category, representing 79 per cent of the grouping.

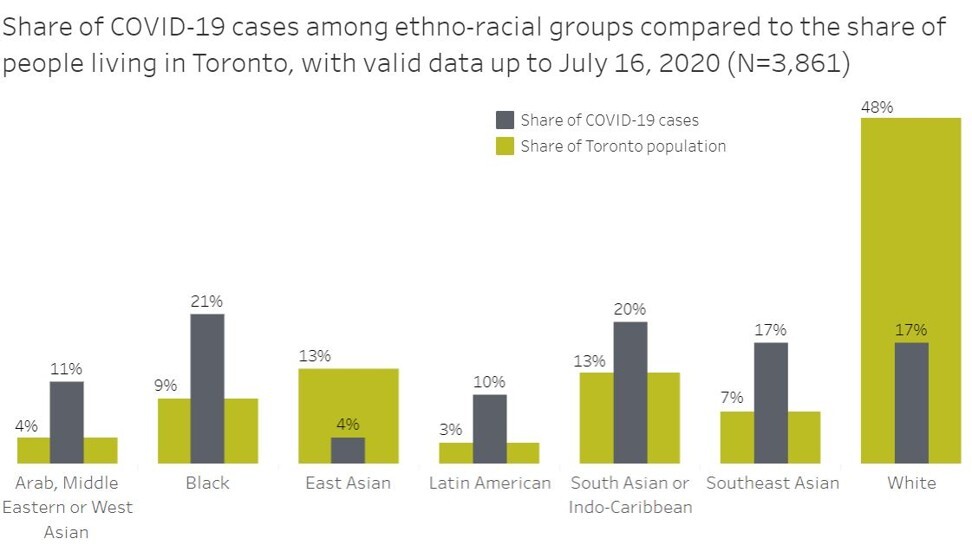

East Asians had a Covid-19 rate of 40 infections per 100,000, far below the citywide rate of 145. They make up 13 per cent of the City of Toronto’s population of about 2.7 million – but less than 4 per cent of all infections.

The second-lowest infection rate (50 per 100,000) was among whites, who make up 48 per cent of the city’s population, and 17 per cent of infections.

Every other ethnic group has fared much worse.

The highest rates are among Latin Americans (481 per 100,000) and Arab/Middle Eastern/West Asians (454 per 100,000). Those communities are relatively small, at less than 3 and 4 per cent of the city respectively – but they suffered 10 per cent and 11 per cent of all Covid cases.

Asians in the US least likely to get coronavirus infection, data suggests

The larger populations of black Torontonians and Southeast Asians had identical infection rates of 334 per 100,000 people. Blacks make up about 9 per cent of the city, and Southeast Asians about 7 per cent, but experienced 21 and 17 per cent of all infections respectively.

South Asians (grouped with Indo-Caribbeans), had an infection rate of about 224 per 100,000. They make up about 13 per cent of Toronto, but have suffered 20 per cent of infections.

Canada has not been releasing race-based Covid-19 data on a national level, something critics call a blind spot.

But the Toronto data echoes previous geographical data from British Columbia, where the rate of Covid-19 infection in Richmond – the most ethnically Chinese city in the world outside Asia – has been the lowest in the metro Vancouver region.

In her presentation last week, Dr de Villa said there was “growing evidence … that racialised people and people living in lower-income households are more likely to be affected by COVID-19“.

“While the exact reasons for this have yet to be fully understood, we believe it is related to both poverty and racism,” she said.

Did data secrecy help an anti-Chinese virus to spread in Vancouver?

She noted that 83 per cent of reported COVID-19 cases in Toronto involved a patient who identified as a member of a racialised group, compared to 52 per cent among the general population.

The race-based data from Toronto showed that “risk distribution was very unequal”, said Dr David Fisman, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto. But this could be an overlapping function of wealth and income, he said.

There were dramatic differences between infection rates depending on income, with the rate steeply declining as incomes rose. The infection rate among residents of households earning C$150,000 (US$113,000) or more was 24 per 100,000 – less than one-sixth the rate suffered by the lowest earners, on less than C$30,000 per year, at 160 infections per 100,000.

“We were seeing this anecdotally in hospitals; the lockdown extinguished spread [of Covid-19] in higher-income areas, as a lot of professionals with service jobs got to go online,” he said.

“Lower-income folks are more likely to be people of colour and more likely to be in essential in-person work,” such as jobs in factories, food processing or care facilities, Fisman said.

Suspect in racist Covid-19 incident on Vancouver bus is dead

“We can see that the epidemic split off in Toronto into two epidemics: one for wealthier Torontonians, and another, more prolonged, epidemic for those of lesser economic means.”

Kindrachuk agreed – the income divide was “eye-opening”, he said. “If you have a high income, you likely are going to be able to weather the storm … there is a complete disparity between how the burden of this disease looks between high and low income brackets.”

As for genetics, Kindrachuk said he doubted that it explained the stark disparities among ethnicities. “I haven’t seen evidence that there is a difference” on a genetic basis, he said.

He said that more data, showing infection rates within each ethnicity according to income, was needed before drawing conclusions about the impact of those two variables, relative to each other.