Review | Massacre in Manila: the forgotten second world war battle that destroyed a city and countless lives

- Unlike the Rape of Nanking, the appalling atrocities perpetrated on civilians by Manila’s Japanese defenders have been largely forgotten – until now

- This groundbreaking history mines war crimes records, military reports and other sources to reveals the full horror of the Battle of Manila

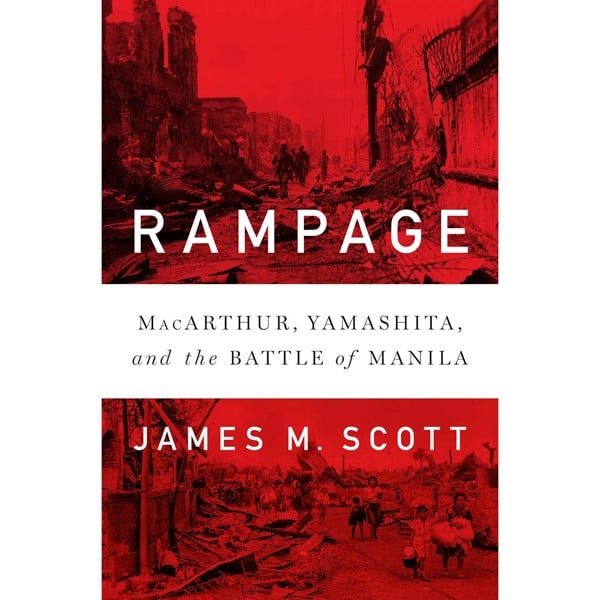

Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita, and the Battle of Manila by James M. Scott, pub. W.W. Norton

4 stars

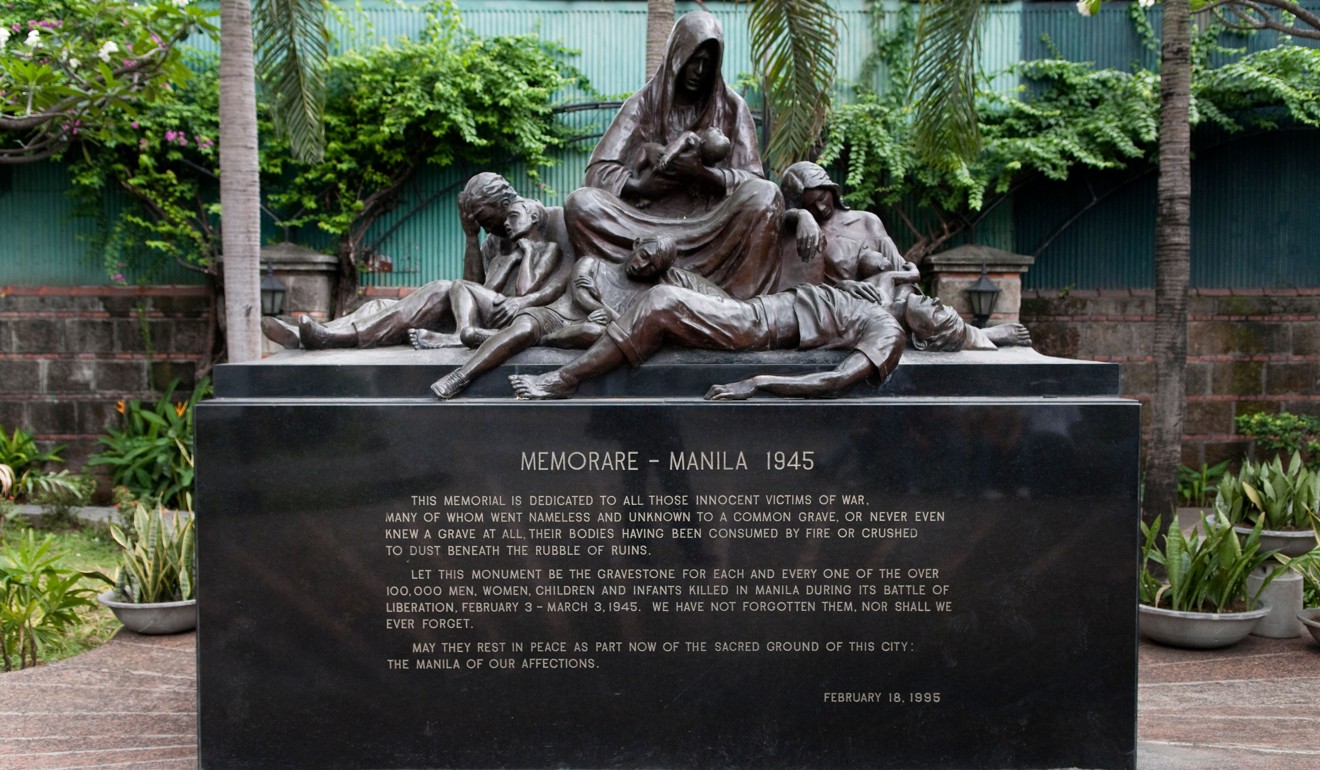

It’s hard to imagine that a major month-long battle during the second world war – one that devastated a large city, caused more than 100,000 civilian deaths and led to both a historic war crimes trial and a United States Supreme Court verdict – should have escaped scrutiny until now.

But history has somehow overlooked the catastrophic battle for Manila, capital of the Philippines, in the waning months of the war. Like the Rape of Nanking, or the siege of Stalingrad, the tragedy of Manila deserves far greater understanding and reflection today.

President Duterte the aggressive narcissist, and why he has so many fans

James M. Scott fills that gap with Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita, and the Battle of Manila, the first comprehensive account of one of the darkest chapters of the war in the Pacific. It is powerful narrative history, one almost too painful to read in places but impossible to put down.

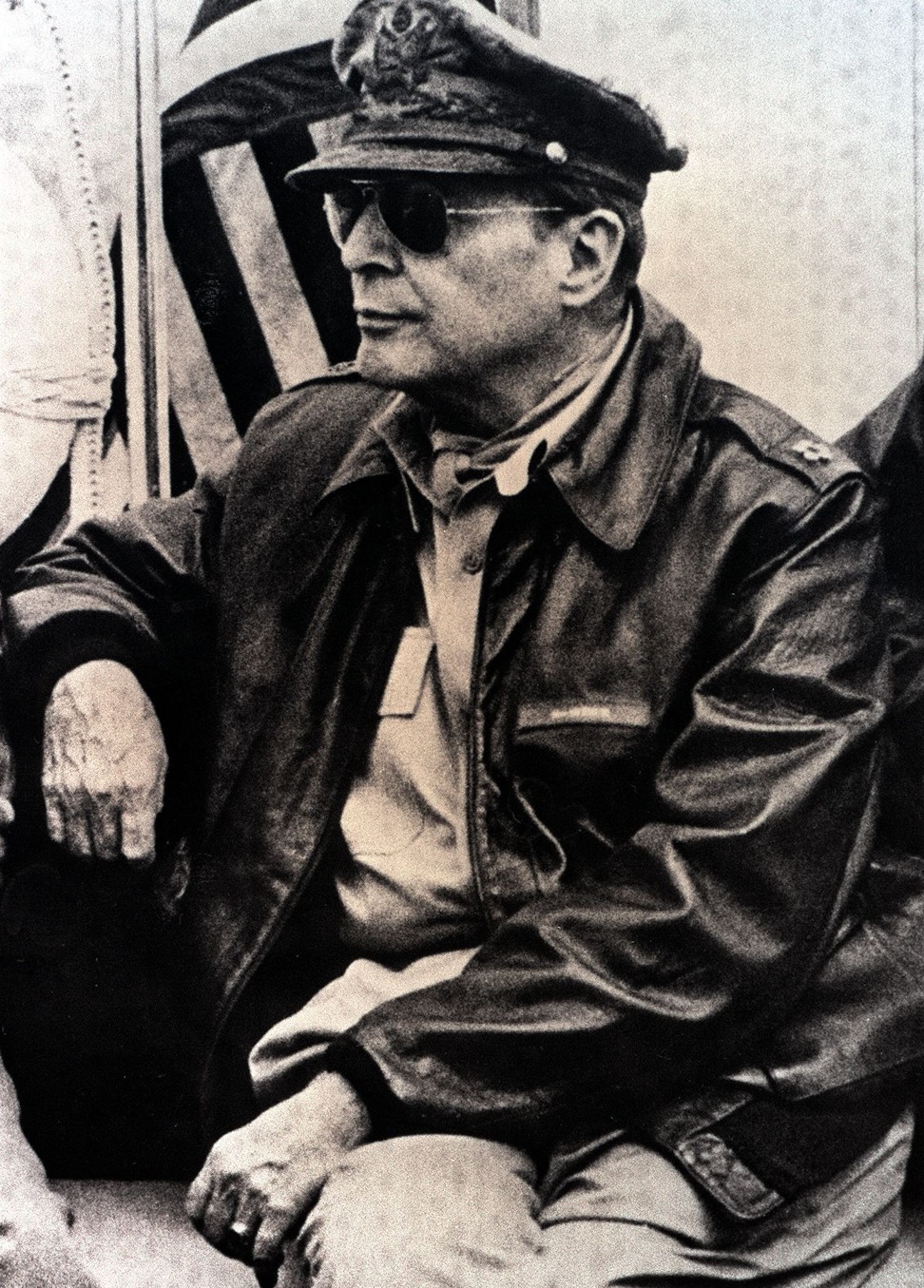

It begins with General Douglas MacArthur, the egotistical military commander of the US colony in the Philippines, caught woefully unprepared when the war began. Japanese bombers destroyed his planes on the ground and American and Philippine forces were soon overwhelmed. MacArthur famously vowed to return as he was evacuated to Australia.

Three years later, the US Navy had steadily clawed its way back across the Pacific and bombers were already striking Japanese industrial centres. Most commanders saw “no need to risk American lives on a costly invasion of the Philippines” when the fall of Japan appeared imminent, Scott writes.

But MacArthur insisted, and by early 1945 his troops were closing on Manila. Americans knew it then as the “Pearl of the Orient” for its neoclassical buildings, grand boulevards and cafe society. Convinced the Japanese would abandon Manila, just as he had, MacArthur ordered up a massive victory parade to welcome himself home.

On February 6, 1945, MacArthur pre-emptively announced the city’s liberation, claiming credit in grandiose terms. Congratulations poured in from Washington, London and elsewhere. But the 29-day battle had only just begun. MacArthur’s public relations stunt meant reporters travelling with his forces struggled to get the truth out about the unfolding horror.

The Japanese commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, had stunned allies early in the war by seizing Malaya and Singapore, capturing a much larger British force. His orders now were to bog MacArthur’s forces down in the Philippines and give Japan time to prepare for the expected US invasion. He ordered subordinates to destroy Manila’s bridges and port, and then to follow him to the mountains.

Once Yamashita withdrew, however, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi instead ordered his marines to “fight to the last man”. They methodically dynamited Manila’s business, government and religious landmarks, obliterating the city’s cultural heritage, and torched thousands of wooden homes, sparking a deadly firestorm. Worse, they cruelly tortured and killed thousands of men, women and children.

Scott, who was a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist for Target Tokyo, focuses in part on the 7,500 or so Americans and others held as prisoners of war or civilian internees in squalid conditions, and their dramatic rescue by US troops. Although some of those stories are familiar, he adds a heart-rending portrayal of the brutal life they endured.

But Scott breaks new ground by mining war crimes records, after-action military reports and other primary sources for the agonising testimony of Philippine survivors and witnesses of more than two dozen major Japanese atrocities during the battle – and the ferocious American response. The frenzy of Japanese massacres defies imagination.

Countless women were raped and tortured, their babies tossed in the air and bayoneted. Patients and doctors were stabbed at hospitals, nuns and priests hanged at churches, children tossed into pits with grenades. Marauding Japanese troops burned people alive in convents, schools and prisons. They simply buried others alive.

In one charnel house, they cut a hole in the second floor and then led scores of blindfolded civilians upstairs, made them kneel by the edge and decapitated them with swords. Elsewhere, they crammed hundreds of men into a sweltering stone dungeon, locked the iron door and let them starve to death.

A Japanese soldier’s diary relayed the horrors at Fort Santiago, an ancient citadel. “Burned 1,000 guerillas to death tonight,” the diarist wrote on February 9, one of several such entries. The mass murder was not random. Military orders later found by investigators stated that “all people on the battlefield … will be put to death”. The battlefield was the entire city.

Against them was a US force unprepared for urban warfare. They fired 155-millimetre howitzers at point-blank range to dislodge the enemy and used tanks, flame throwers and bazookas to kill the rest. They fought block by block, house by house, room by room, levelling hundreds of city blocks.

US troops rescued, treated and fed tens of thousands of traumatised and wounded survivors. But amid the smouldering ruins, Scott writes, “it was hard to tell who had done more damage – the Japanese defenders or the American liberators”.

Estimates of the civilian dead range from 100,000 to 240,000. MacArthur was mostly absent, writing in his diary that he was engaged in “routine conferences” at a lush hacienda north of the city. Iwabuchi, who had presided over one of the most barbaric massacres of the war, apparently committed suicide rather than surrender, although his body was never found.

The terrible battle had a curious afterlife. Yamashita finally surrendered several weeks after the war had formally ended. US prosecutors soon charged him with failing to control his troops in the deaths of 62,278 civilians, 144 slain American officers and enlisted men, and 488 raped women and children.

Yet the first war crimes trial in the Pacific proved a rushed, makeshift affair. Yamashita was not charged with taking part in the atrocities, or ordering them, or even knowing about them.

“The rule of evidence,” a New York Times reporter wrote at the time, “can be boiled down to two words: anything goes.”

Not surprisingly, he was found guilty and sentenced to hang. His American lawyers filed an emergency appeal to the US Supreme Court. It ultimately ruled 6-2 against Yamashita, dooming him to the gallows, but is remembered mostly for the two impassioned dissents.

“Never before have we tried and convicted an enemy general for action taken during hostilities. Much less have we condemned one for failing to take action,” Justice Wiley Rutledge wrote. Justice Frank Murphy was even more blunt. The “enemy has lost the battle but has destroyed our ideals”, he warned.

British author in Hong Kong on his obsession – 1930s Shanghai

Those still fascinated by the second world war will find much new to ponder in Rampage.