Tributes flow for Hong Kong’s first Chinese prosecutor Patrick Yu, after death at 96

- Celebrated criminal barrister is remembered for turning down three offers to become a judge on Hong Kong’s highest court, citing discrimination in favour of expat practitioners

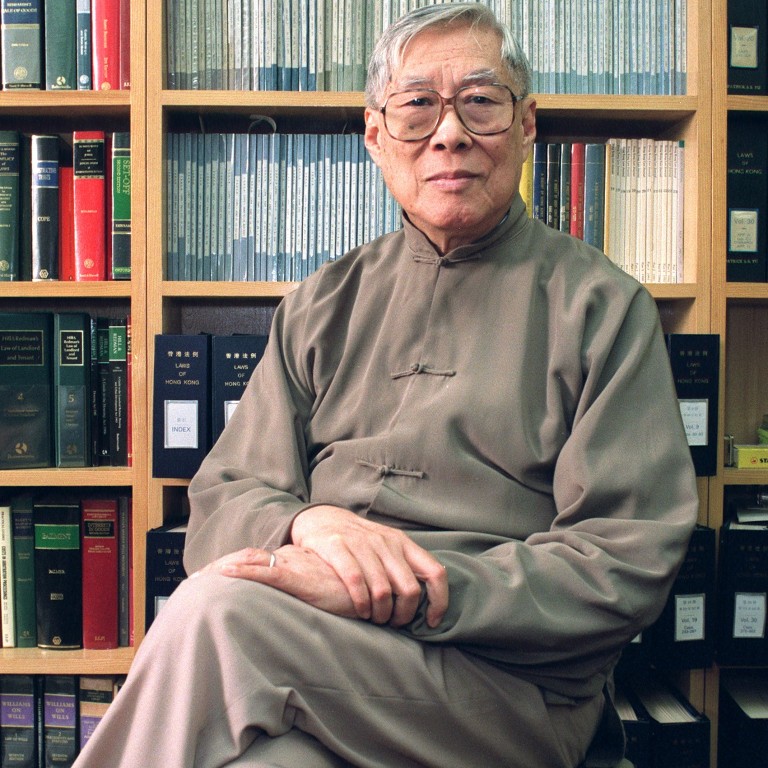

Hong Kong legal heavyweights have paid tribute to the city’s first ethnically Chinese prosecutor, Patrick Yu Shuk-siu, who died on Saturday aged 96.

The celebrated criminal barrister is remembered for turning down three offers in the 1970s to become a judge on Hong Kong’s highest court. He cited discriminatory employment terms against locals as the reason.

Yu was also known for his stern opposition to the appointment of lawyers as queen’s counsel, later renamed senior counsel, for which he said there were no objective criteria.

He never applied for the title throughout his 30-year career, during which he was a mentor and leading counsel to a number of lawyers who went on to become top judges.

Yu played an instrumental role in establishing the city’s first law school, at the University of Hong Kong, in 1969.

Former Bar Association chairman Martin Lee Chu-ming said Yu had been in poor health, both mental and physical, when they last met several months ago. Yu was Lee’s godfather.

“He was a perfectionist, and when he found he was not quite his best self, he retired,” Lee said. “He’d always have to be 100 per cent ready.”

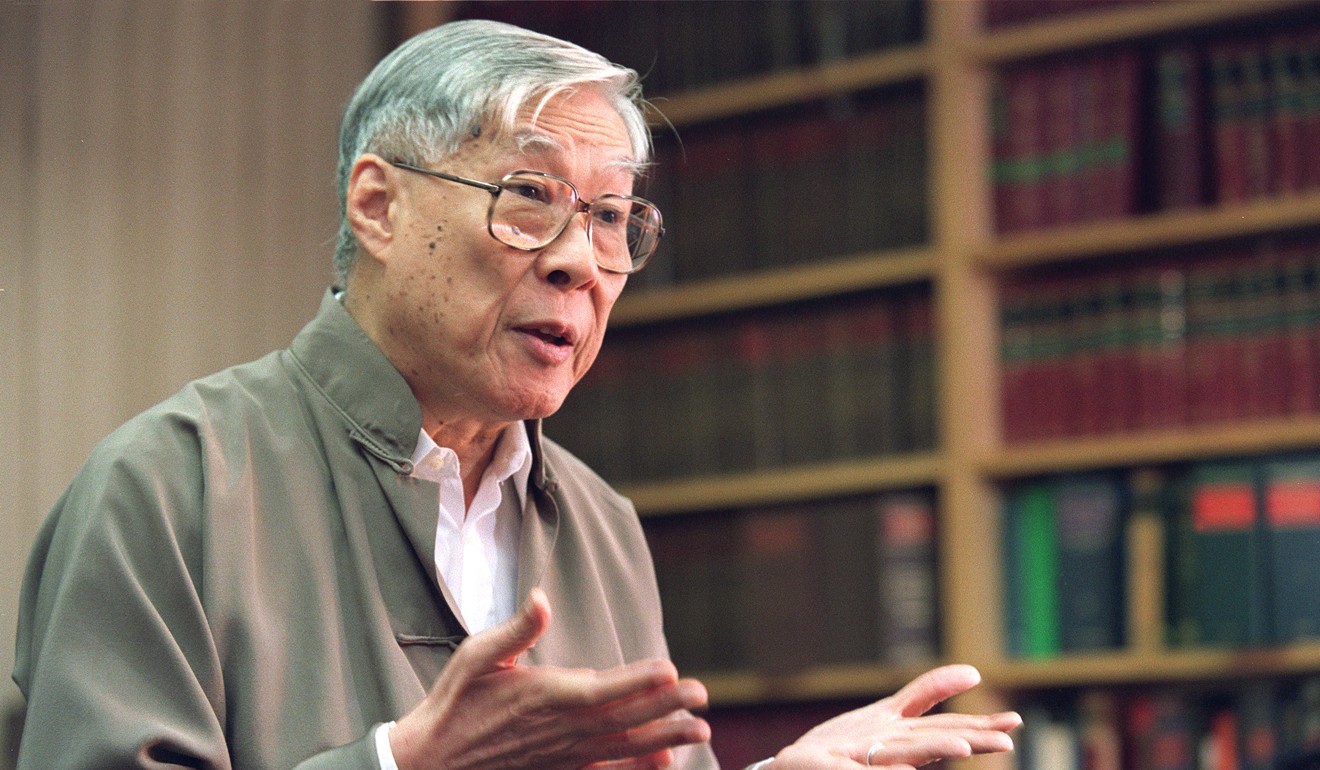

Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li hailed Yu as “the best of his generation”, and said he was unshakeable in his pursuit of the rule of law and had influenced generations of lawyers and judges.

“Mr Yu was for many lawyers in Hong Kong, including judges, barristers and solicitors, an inspiration, and represented the ultimate aspiration as to the qualities required in the law,” Ma said. “Patrick will be much missed but his generosity of spirit and his ideals will live on.”

Senior counsel Lawrence Lok Ying-kam said: “Unlike most criminal barristers, he was very sincere and always well reasoned – not like those silks who keep banging the table in court.”

HKU law dean Michael Hor Yew Meng also paid tribute to Yu for his work securing justice for defendants from poor backgrounds.

Yu was born in Hong Kong in 1922. He studied at HKU but missed his last year due to the second world war. He later served in the intelligence corps for the Republic of China before the communist revolution in 1949.

After the war he was awarded a government scholarship to study politics, philosophy and economics at the University of Oxford. He first began practising law in Malaysia.

The legal profession in the colonial era was dominated by British and Commonwealth practitioners. Yu maintained that employment policy was discriminatory and called it distasteful.

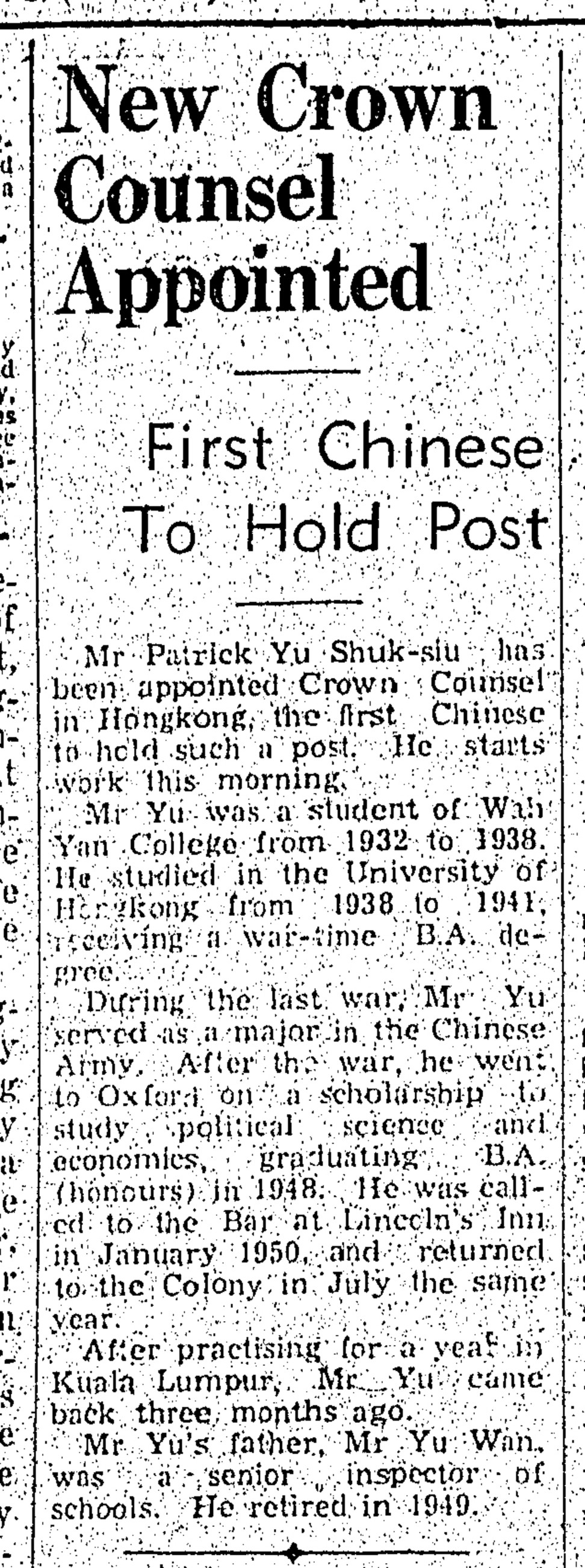

Nevertheless in 1951 Yu became the first Chinese to be appointed a crown counsel, as the colonial government grappled with a growing number of bilingual court cases. He resigned one year later in protest at discrimination against local lawyers.

His appointment had been backed by two attorneys general who promised to employ him on the same terms as expatriates, but he was eventually denied a housing allowance and the paid leave given to other government prosecutors.

Yu later turned to private criminal practice, but his fight against colonial discrimination had not been in vain, according to a book he published in 1998 titled A Seventh Child and the Law. Following his resignation the government introduced housing allowances for local civil servants and the pay gap gradually narrowed.

Yu was offered three terms on the Supreme Court bench by three consecutive chief justices, in 1970, 1973 and 1979.

“But on each occasion our dialogue broke down as soon as I insisted on being granted equal terms with the expatriate judges,” Yu wrote.

He welcomed the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, saying it would “surely mark the end of discrimination once and for all”.

But Yu believed there was no way Chinese could replace English as the language of legal argument, as no translations existed of legal principles or case law.

After retiring in 1983, Yu rarely commented on public affairs. But in 2002 he voiced rare support for a legal interpretation issued by Beijing of Hong Kong’s mini-constitution.

He was often praised by fellow lawyers for his cross-examination skills.

“He had a photographic memory,” said Lee, now Hong Kong’s most senior barrister.

“When we used to prepare closing submissions for a case, he would invite me to dinner at his home the night before to ask how we should word the legal points. But he never had to take notes – not a single word.”

Yu’s family said he died peacefully on Saturday and that arrangements for a memorial service would be announced later.