30 years on from Tiananmen Square crackdown, why Beijing still thinks it got it right

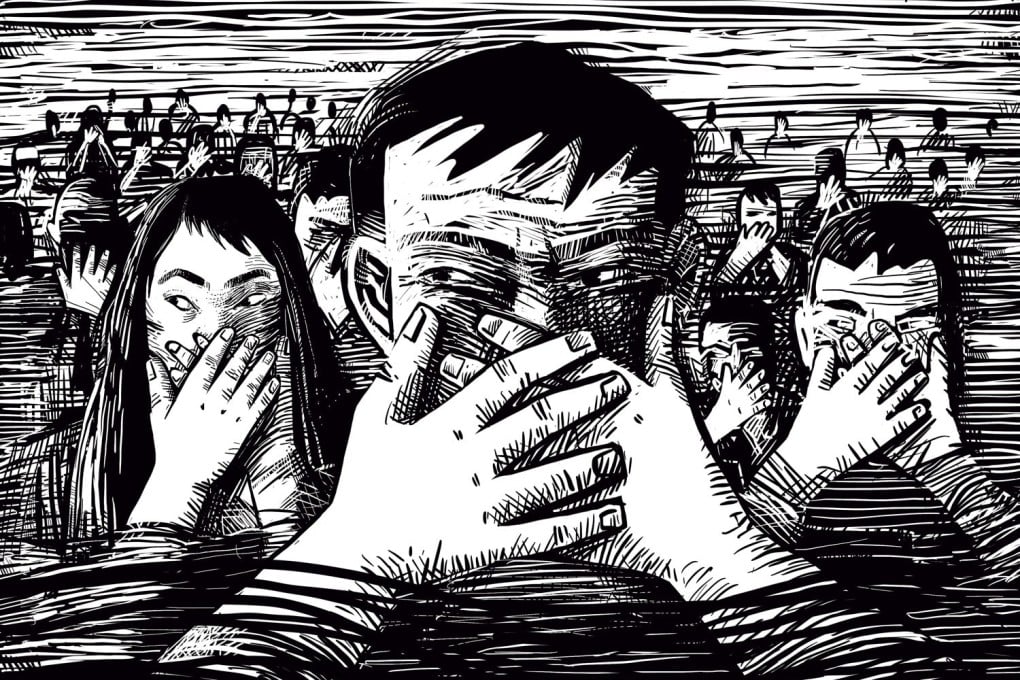

- Three decades have passed since the Tiananmen Square crackdown when troops fired on student-led pro-democracy protesters

- The shots were heard around the country and reverberate today despite persistent official censorship of the events

In the first of a six-part series, Jun Mai looks at why the Communist Party refuses to reverse its condemnation of student-led pro-democracy protests that were subject to a bloody crackdown in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

When US president Ronald Reagan and Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang walked out of the White House arm in arm on January 10, 1984, a sense of optimism and hope swept across the Pacific.

Nobody could have missed the symbolic and diplomatic importance of Zhao’s visit, which also underscored his leadership position in the Chinese hierarchy. Moreover, the American public liked this all-smiling new face of China. Many were convinced that Zhao’s trip would mark the beginning of a relationship that could shape the world and transform the ancient Asian civilisation into something “more like us” in the process.

Fast forward to June 1989, Zhao, now head of China’s Communist Party, finds himself a prisoner of his own state after two months of dramatic twists and turns and political infighting in Beijing. An unprecedented student-led demonstration against corruption erupted in April and spread across China like wildfire. Zhao, who sympathised with the students, lost the political battle and trust of paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

The protest was later branded as an “antirevolutionary riot” and brutally put down in a fashion that shocked the world. Zhao was placed under house arrest for the alleged crime of “splitting the party”.

Even in the depths of his despair, Zhao, whom US historian Ezra Vogel once described as the real architect of China’s reform programme, remained hopeful that one day the party would vindicate his decision and reverse its verdict on the student movement.