Why China’s private firms aren’t convinced the law will protect them

- Despite Beijing’s promises to support the sector, entrepreneurs still fear government intervention in the legal process for political aims

China’s private sector, the driving force behind the country’s economic miracle over the last 40 years, is struggling amid the Chinese government’s campaign to reduce national debt and the trade war with the United States. This is the final story in a series detailing the challenges private firms face and outlining the government’s attempts to address them.

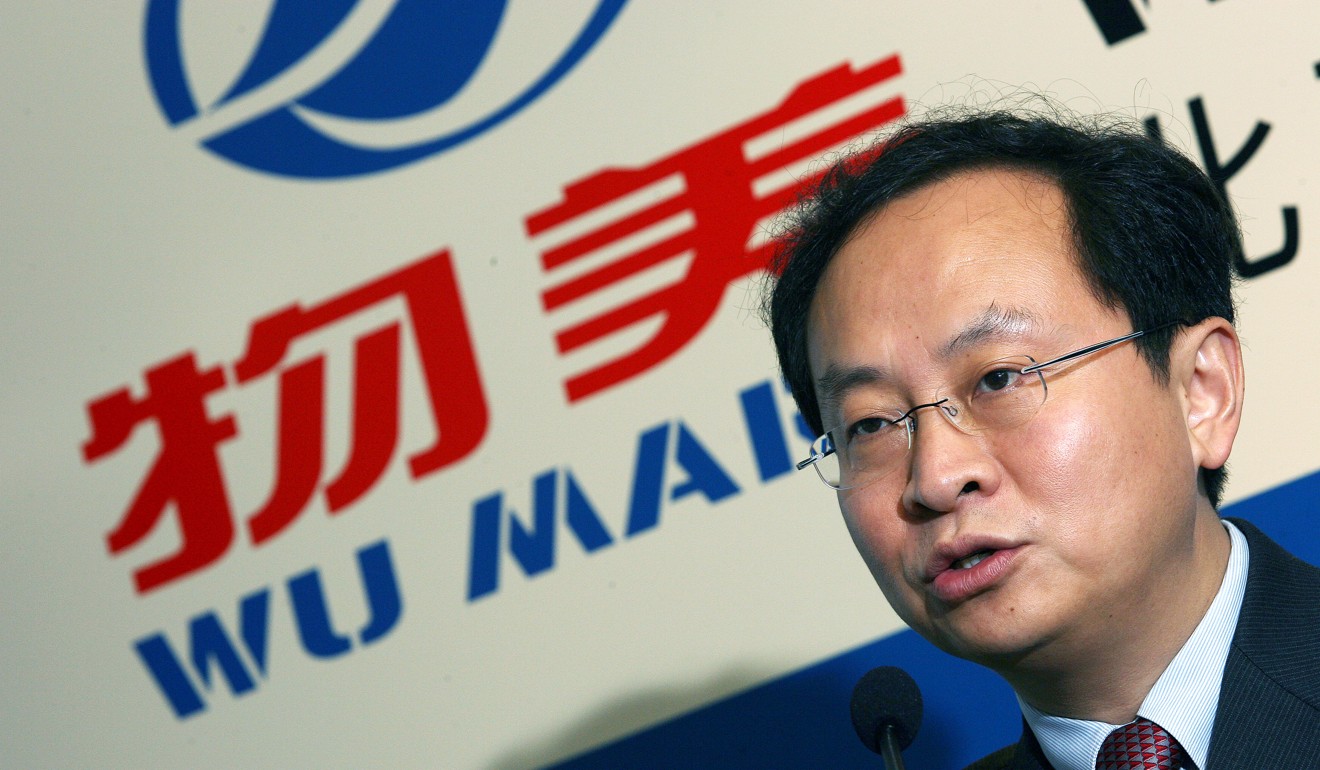

When supermarket tycoon Zhang Wenzhong spoke at this year’s Yabuli forum of entrepreneurs, his message struck right at the heart of what keeps private business owners in China awake at night.

The 56-year-old founder of Wumart Stores, one of the country’s biggest retailers, had just resurfaced in public having spent seven years in prison before being freed when his conviction for fraud, bribery and embezzlement was overturned.

“Without outside intervention or influence, no law enforcement agency – police, prosecutors or courts – would have reached such a verdict against me under normal circumstances, creating a case so unjust that it is now easily judged as a mistake,” he told the annual gathering in northeastern Heilongjiang in February.

He went on to issue a chilling warning to anyone running a business in China’s government-controlled environment.

“This doesn’t just concern me – it concerns all entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship,” Zhang said, reading from a letter he had written.

Can China’s leaders restore confidence to private businesses?

His case is one of three cited by the Supreme People’s Court in its annual work report this year as evidence of moves to protect private ownership and correct unjust verdicts.

The Wumart founder was acquitted of all charges on May 31 and his property and assets were returned to him. Released from jail in 2013, it took five years to clear his name.

‘Original sin’

But Zhang’s exoneration a dozen years on from his trial has done little to ease the fears of Chinese businesspeople. Many are haunted by their “original sin” – the questionable ways some amassed wealth in China’s underdeveloped legal environment – and are criticised over the widening gap between rich and poor amid a resurgence in communist ideology, in contrast to the 1980s when Deng Xiaoping encouraged a few able Chinese to become rich.

The threat of being accused of “original sin” has for years weighed on Chinese entrepreneurs, as past deeds could be traced – no matter how trivial the offence – and used as evidence in a prosecution.

President Xi Jinping attempted to address those concerns at a high-profile private economy meeting on November 1.

“With regard to the previous non-standard practices of private firms, [we] must take a development perspective, and deal with them based on the principles of no penalty outside the law and presumption of innocence. By doing that, entrepreneurs can cast off mental burdens and continue with their minds at ease,” he said.

Xi also highlighted the correction of past wrongful verdicts, saying it helped to restore investor confidence.

“We must screen out and correct a number of wrong verdicts concerning corporate ownership,” he said.

China’s private firms shy away from bank borrowing, delaying investment

Despite numerous recent assurances from Xi and top Chinese officials, analysts still question the government’s sincerity in promising to protect and aid the private sector.

Rather, they wonder if the statements are just expedient to help stabilise the national economy at a time when it is growing at its slowest pace in a decade and many private businesses are struggling to survive, as the trade war with the US rages on.

“A few individual [court] cases don’t represent a [change in the] whole situation,” said Tang Dajie, secretary general of the China Enterprise Institute, a Beijing-based non-governmental organisation.

Tang, whose institute has called for tax relief, wider market access and better legal protection for private firms, attributed the government’s recent change in tone in favour of private enterprises to its need to address increasing downward pressure on the economy.

Even though charges of bribery against entrepreneurs have diminished since 2013 due to Beijing’s corruption crackdown, private firms are struggling to cope with an abrupt rise in environmental protection standards, stricter social tax collection and a deterioration in the business climate.

Businesspeople argue that the difficulties facing private firms will not be solved until the boundary between government and the market is handled fairly.

“The Chinese government should ask itself whether the economy is overregulated and how much state-owned enterprises have restricted the room for private firms to develop,” Tang said.

Charm offensive

According to state media, Beijing is sincere in its promise to protect the private sector and promote entrepreneurship, and the ruling Communist Party released guidelines in September last year that resulted in the Supreme People’s Court decision to re-examine historical cases involving convictions of entrepreneurs.

As part of its private sector charm offensive, the government recently commended 40 entrepreneurs for their contributions to China’s economic miracle of the past four decades.

Xi also described the private sector as “one of us” and said that the government would take steps to support it.

“Our basic economic system has been written into the country’s and the party’s constitution. It won’t change,” he told 54 well-known entrepreneurs at a symposium on November 1.

But private-sector business owners remain on edge. In late September, a widely circulated online post argued that the “private economy has completed its historic mission and should quit”. That followed a series of speeches by top government officials, including the president, extolling the importance of state-owned enterprises – causing near-panic among the business community.

Their sense of insecurity has contributed to rising numbers of successful entrepreneurs moving their assets, and their families, overseas to avoid any political entanglements.

How US trade war could leave Chinese private firms at risk of being ‘taxed to death’

Prior to the trade war, a vast majority of people applying for the US EB-5 visa – for investment immigrants – have been Chinese. They are also the top buyers of property in Toronto, Los Angeles, Sydney and London.

National outbound direct investment, led by private firms, reached a record high of US$170 billion in 2016, according to the Ministry of Commerce. It dropped 29.4 per cent to US$120 billion last year after the government curbed “irrational investment”, which generally refers to private investment in overseas property, entertainment venues, sports clubs and hotels.

Xu Xiaonian, a professor at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai, suggested that a reduction in the state economy, market deregulation and relief on corporate cost burdens would give entrepreneurs an incentive to stay.

But the government’s top priority should be to ensure legal protection for private ownership, he was quoted as saying at a recent forum by the Jiemian News website.

The release of government documents supporting this goal has been helpful, Xu said. But they usually failed to achieve the desired results because some guidelines were contradictory.

“What is the most effective way to protect ownership? [It’s] rule of law, rather than the rule of individuals,” he concluded.

Foreign scepticism also persists on a variety of issues, including market access, national treatment and intellectual property rights protection.

Immediately after Xi promised further market opening and a level playing field for international firms at the first China International Import Expo on November 5, the EU Chamber of Commerce in China released a statement saying that the vast majority of such commitments “remain unrealised”.

“If national treatment is the goal, laws that differentiate foreign-invested from domestic enterprises should be abolished, and all businesses in China should operate under a uniform company law,” the chamber said in the statement.

Lester Ross, a managing partner of US law firm WilmerHale, said lax enforcement of existing laws had also been an issue. “Changes in law are necessary but not sufficient. Implementation in accordance with law is also needed,” he said.

Catastrophic results

Compared to foreign businesspeople who can easily divert their investments elsewhere, unjust actions against individual Chinese entrepreneurs can have catastrophic results for them and their families.

Zhang, who was ranked No 183 on the Forbes list of the richest Chinese in 2006, suffered “heavy blows” that year while he was prosecuted. Many of his business deals were cancelled. Trading in Wumart, which was then listed in Hong Kong, was suspended for months and the company survived under the management of his family.

Zhang’s lawyers, Zuo Jianwei and Zhao Bingzhi, said they quickly discovered that private firms generally lacked the same legal protections as their state-owned rivals.

The country’s criminal law does not clearly protect the interests of joint ventures between Chinese and foreign firms, while private enterprises are more vulnerable to local authorities misusing their administrative powers to illegally seize or dispose of their assets, the lawyers wrote in Procuratorate Daily in August 2017.

Responding to such calls, the high court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the Ministry of Justice recently rolled out initiatives to address the most grievous cases involving private-sector firms.

Will China make good of its latest promise to give private firms more access in a market that favours the state sector?

But according to Beijing-based independent economist Hu Xingdou, a private firm can still be investigated for alleged abuses since administrative power often overrides the law and the government has a tradition of intervening in economic activities.

A private company’s reputation, if not its whole business, can easily be destroyed if they are investigated for tax fraud, a violation of their business scope or if they are accused of associating with a mafia syndicate.

“[These risks] won’t change because of one or two slogans by the top leaders, but need a whole new set of laws, such as implementing the presumption of innocence, no confiscation or freezing of properties [prior to judgment], and the separation of individual and corporate assets,” Hu said.

US trade war forces businesses to rethink Chinese investments amid fears dispute will drag on into new year

“To change the current situation of power overriding the law, reforms in the economic and legal systems are needed. But fundamentally, this demands political reform so that we can contain the power [of the state],” he added.

China’s private sector, the driving force behind the country’s economic miracle over the last 40 years, is struggling amid the Chinese government’s campaign to reduce national debt and the trade war with the United States. This is the final story in a series detailing the challenges private firms face and outlining the government’s attempts to address them.