US indictments against Huawei a step towards splitting the world’s telecoms industry in two

- The Shenzhen-based firm finds itself caught in the middle of a hi-tech arms race between the US and China

The US indictments against Huawei Technologies for violating US sanctions against Iran and stealing trade secrets are seen as the latest steps that could potentially push the world into two distinct camps when it comes to the telecommunications industry.

If Huawei is blocked from providing network equipment to the US and its allies, there is a danger of a split in the industry – where Western companies and Asian firms are only allowed to serve their own markets.

Countries such as Britain, Germany, Australia, New Zealand and Canada have either banned or are reviewing whether to allow Huawei equipment to be installed in their telecoms networks on the basis of security concerns over the firm’s relationship with the Chinese government.

“[In the market,] customers will always be influenced by quality and price,” said David De Cremer, a professor of management and organisation at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and author of the book Huawei: Leadership, Culture and Connectivity. “But if markets do not stay open, and if they have no choice to buy products [whether] from Huawei or Cisco then economic principles will no longer play a role.”

But what may be holding back these countries is the impact of that move on the cost and quality of their telecommunications infrastructure.

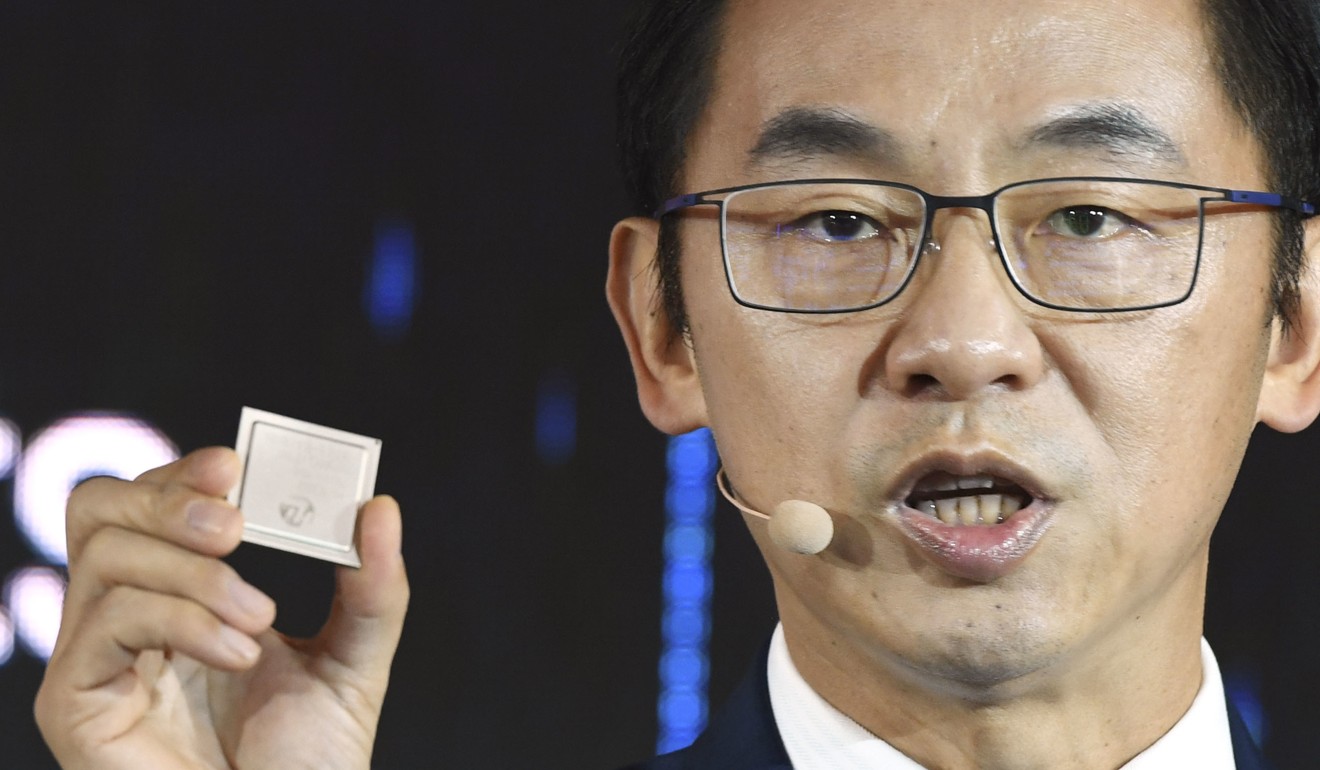

The concerns underscore the market lead that Huawei, which founder Ren Zhengfei started in 1987 as a company selling telephone switches, has built for itself as the world’s largest telecoms equipment supplier.

The Shenzhen-based firm’s success can be attributed to the confluence of good timing, a large domestic market that allows for economies of scale, a hard-charging corporate culture and the discipline to reinvest revenue in advanced research and development.

US President Donald Trump’s administration has been applying pressure on the country’s allies in a campaign to prevent Chinese companies from supplying telecoms gear for 5G networks around the world, according to a report published last week by The New York Times.

The report draws a picture of the Trump administration viewing itself as engaged in a new arms race against China involving advanced technology. It is a zero-sum game in which the loser bows out, the report said.

Huawei did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The privately held company remains a key pillar in China’s fast-developing technology sector and an important partner in national development.

Ren, who joined the army’s engineering corp as a youth, founded Huawei amid a government push to build up China’s weak telecoms infrastructure after the country opened up and pursued economic reforms.

At the time, one of China’s strategies was to import foreign telecommunications equipment, and companies like Cisco entered the Chinese market and had as much as 60 per cent market share for network solutions.

But that strategy ended in 1996, when the government focus shifted towards supporting domestic Chinese telecoms firms like Huawei, instead of foreign equipment suppliers.

By then, Huawei had already established research and development centres across China to focus on mobile communications equipment and establish a foothold in building the telecoms systems in rural areas, which foreign companies had neglected, according to a Huawei case study from the Centre for Strategic & International Studies.

“Huawei was going the extra mile to build telecoms networks in [rural areas] in the mountains or in politically unstable markets,” said De Cremer.

“That’s where they had that competitive difference … Huawei would serve its customers at any cost.”

They also managed to produce networking equipment at 70 per cent lower cost than rival Cisco, giving Huawei a competitive edge.

But good timing and a large domestic market would not have mattered had the company not placed an emphasis on research and development.

Huawei recently pledged to spend at least US$15 billion on such efforts. The company also collaborates and funds university research around the world.

“At this point, Huawei has access to a lot of manpower in China,” said Lim Teng Joon, a professor at the department of electrical and computer engineering at NUS.

“On top of that, they also offer implementation [of their systems] and marketing. It’s a full range of services provided at a more competitive cost than their rivals and that’s why they are hard to beat at the moment.”

Lim said Western countries that block use of Huawei’s equipment in their markets means that telecoms network operators will have a higher price to pay for the same sort of products offered by the Chinese firm’s rivals, while potentially receiving a less comprehensive set of services or technology.

“It’s difficult for a company to be able to provide such hi-tech equipment for all parts of the business, because it is expensive to develop and the implementation is highly sophisticated,” he said. “The barrier to entry is very high.”

Huawei’s aggressive efforts to capture new business so quickly outside its home market is part of its corporate culture – known internally as “wolf culture” – that encourages employees to be sensitive to market opportunities, to always push forward and to work in teams.

Underpinning that “wolf culture” is also a strong mission and management style that Ren modelled after the West.

In 1996, around the time that Huawei began considering international expansion, the company engaged IBM to help reorganise its management structure, as the company “didn’t have any”, according to NUS’ De Cremer.

“Ren Zhengfei has always been a person inspired by the West as well … they had a very strong learning orientation and dedication of willing to sacrifice for their clients,” De Cremer said.

“[To Ren], the customer is more important than your boss. That’s a very different mindset from Chinese companies in the 1980s and 1990s.

“They’ve always been very strict in terms of training and focus on what are legal regulations across the world, what are the rules [Huawei] has to comply with [in international expansion]. Huawei tried to accommodate much quicker than other Chinese companies.”

Huawei’s global workforce was also expanded during the financial crisis, when the company was able to scoop up foreign talent amid the lay-offs at many hi-tech and telecoms companies. That helped the firm’s workforce became much more diverse, intercultural and globally focused.

At present, Huawei continues to grapple with the US request to extradite the company’s former chief financial officer and Ren’s daughter, Meng Wanzhou, to the US from Canada, after her arrest in December and subsequent release on bail. With the indictments against Huawei, Meng is expected to stand trial in the US.

Canada’s ambassador to China, John McCallum, was fired by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau last week after the former remarked that the extradition request was flawed and that it would be “great for Canada” if it was dropped.

Technology companies, from hardware makers to software developers, face security questions as their products and services become ever more intertwined with daily life.

Social media giant Facebook, for example, has been accused of inadequate oversight for allowing Russian interference that ultimately affected the last US presidential election by allowing external parties to access its data.

“Now we are living in a world of cyber insecurity and every leading telecoms equipment vendor and carrier as well as IT and social media companies is a potential target of national security agencies worldwide,” said John Ure, director of the Telecommunications Research Project at the University of Hong Kong and author of Telecommunications Development in Asia.

“This is a general trend and it is difficult to see ways to create ‘safe harbours’,” Ure said. “In decades gone by, it was all about national champions, then it became more global, and now its reverting to national security issues.”