Exclusive | The high price of denial: the cost to China of sweeping the Tiananmen crackdown under the carpet

- Three decades have passed since the Tiananmen Square crackdown when troops fired on student-led pro-democracy protesters. The shots were heard around the country and reverberate today despite persistent official censorship of the event

- For those 30 years the Communist Party has refused to revisit June 4, doubling down against calls to check its power

In the second instalment in a six-part series, Josephine Ma and Guo Rui look at how the party’s long-term authoritarian survival strategy raises big risks of its own.

When You Weijie’s husband was killed in the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, the only official acknowledgement she received was a small cash payment from her work unit.

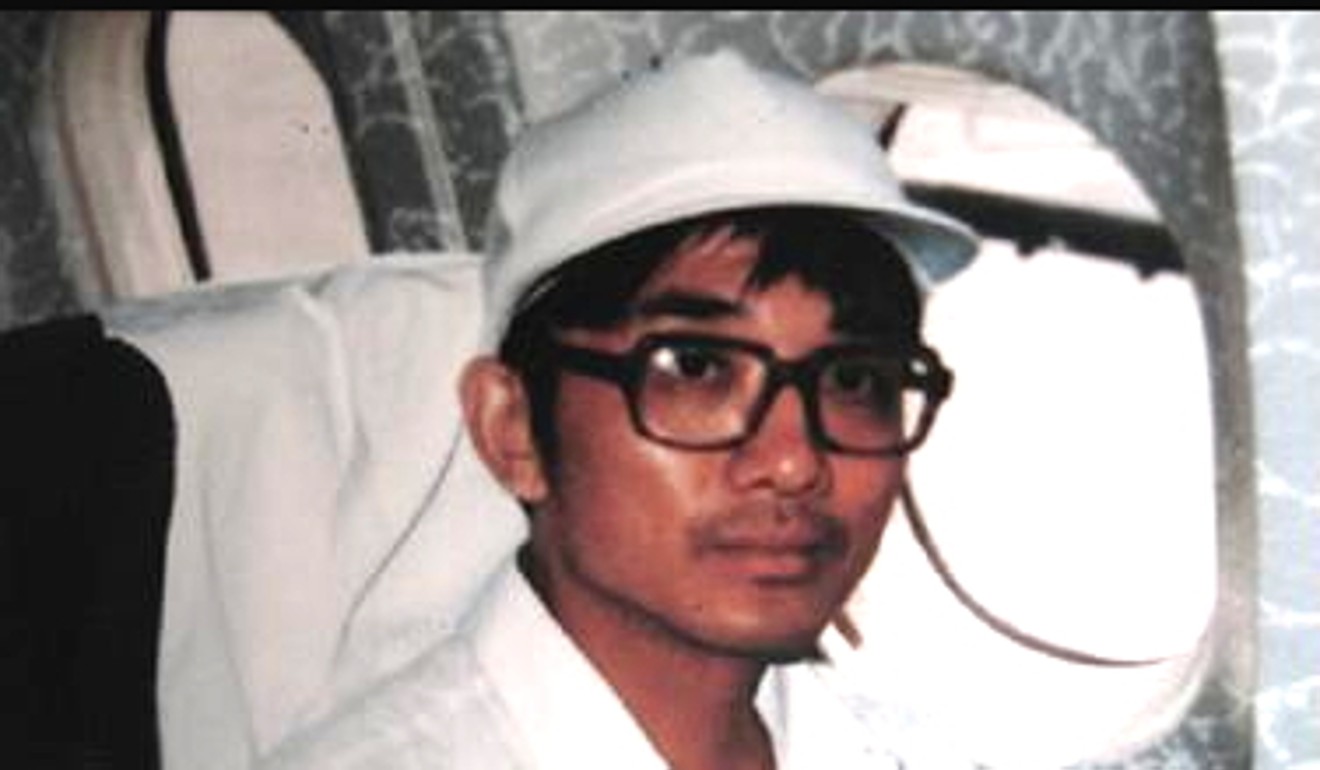

You’s husband, 42-year-old patent office worker Yang Minghu, was caught in gunfire on a Beijing street as the military advanced to the square to enforce martial law.

Yang was sympathetic to the pro-democracy protesters and left his home early on June 4 to check on their safety.

He was struck by a bullet as troops fired into a crowd, becoming one of the hundreds, perhaps more than 1,000, who died as troops quashed protests that the national leadership saw as a threat to Communist Party rule.

The 800 yuan from You’s work unit was supposed to compensate her for the loss of her spouse’s life; but she returned it. “I couldn’t use the money. I felt that this is a person’s life, this is the price of a human’s life,” she said.

What You, 65, wants is an open investigation into what happened on June 4, and punishment for those responsible for the crackdown. She and other members of the Tiananmen Mothers group also want the party to clear the protesters of blame.

But no vindication has come. Instead, the party has stuck to its verdict, defining the pro-democracy protests as “turmoil”, “counter-revolutionary riots” and “an act against the government”.

For three decades, it has firmly resisted revisiting the period, turning its back on the reformist calls of the time and stifling debate to maintain stability and its own survival.

But observers and insiders say that the party and the country are paying a price for the three-decade-old strategy. They say that by exiling critics to the political wilderness, and by hewing to its authoritarian line, the party’s ability to face challenges will be undermined by the lack of checks and balances. It will also miss the opportunity to clear the stain on its reputation abroad by reconciling with the victims’ families while they are still alive.

30 years on from Tiananmen Square crackdown, why Beijing still thinks it got it right

The Tiananmen protests emerged in the 1980s from the political soul-searching of post-Cultural Revolution China. The public and the political elite were keen to ensure there were enough checks and balances in the system to avoid a repeat of the decade-long calamity that had left the country in ruins.

While Western-style multiparty democracy was always off the agenda, there was debate within the party and intelligentsia about better oversight of the ruling organisation and some degree of separation between its political and executive functions.

“It should be a system to supervise the power of the Communist Party. Power cannot be monopolised,” former party general secretary Zhao Ziyang wrote in his memoir.

At the same time, economic changes were under way, bringing in foreign investment and allowing people to start businesses. The changes brought a degree of wealth but they also resulted in inequality and corruption as a few were allowed to get rich first.

Concerns about graft and debate over the political system came together in the spring of 1989 in the student-led demonstrations in Tiananmen Square.

For about two months, protesters openly demanded change, confronting the party with what some senior members of the organisation saw as a threat to communist rule. Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and conservative party elders were concerned that the demonstrations would spread to other cities and be used by foreign forces to overthrow communist rule.

In the aftermath of the June 4 crackdown, reformists in the party were purged and political stability became the top priority. Out went the drive for checks and balances and in came the fear of unrest. In the years since, the party has maintained its ruling power and kept political reformists at bay.

“Ensuring stability is a child of June 4. After June 4, maintaining stability with force has become necessary,” said Bao Pu, son of Bao Tong, aide to Zhao.

Blood red anxiety: how Tiananmen coloured the world of Chinese artist Chen Guang

In doing so, it has sought to wait out the calls to vindicate the Tiananmen protesters – a strategy designed to minimise risks, analysts say.

Zheng Yongnian, director of the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore, said that if the party reversed its assessment of the movement, it would have to embrace the ideology and values behind it, such as freedom and democracy.

“If you reverse the verdict, the uncertainties are infinite,” Zheng said.

Instead,the party has pursued a neo-authoritarian, inward-looking approach to rule, advocating a strong state to restore national glory. The approach has added fuel to nationalism in China and stifled the idea that China should learn other forms of government, including Western democracy.

Zheng said the West did not axiomatically have the answers but the party had to be open to all sectors of society so that it had the support of a broad base of meritocratic elites, including from business, academia and politics.

“We don’t necessarily have to learn from the West as there are many problems with the multiparty system. However, [it should address the problem about] how to make the party open to all and include all elites,” he said.

Yu Jie, a liberal scholar who went into exile in the United States after he was detained for writing a book critical of former premier Wen Jiabao, said the party also had to tolerate critical voices because they enabled the country to adapt to new challenges. Now, though, there was no tolerance for critical or creative thinkers.

“[The party] is only absorbing those who will propagate, defend and explain its decisions. It turns out nobody can give warnings and correct [the course] if the party makes a wrong decision,” Yu said.

Andrew Nathan, professor of political science at Columbia University, said the party lacked deep legitimacy, and suppressing discussion amplified difficulties when they arose.

“The problem with repressing discussion … is that when, somehow, they do get raised in the public sphere, the shock value and the danger to the regime’s legitimacy is all the greater,” Nathan said.

One consequence of failing to monitor the party over the last three decades has been corruption and rent-seeking by party officials, according to the descendant of one influential communist official.

“Without checks and balances, it is like squatting over a cesspit and trying to kill the flies. The flies keep coming up from the pit,” the source said.

The source said this had led to widespread disillusionment about the organisation and its future.

“Many people have lost their hope in the party. The party is not going to change and it is terminally ill and rotten. Though I personally think there is still hope if we are willing to introduce reforms [for checks and balances] now.”

Much of the critical energy that could be channelled into advancing the cause of the party and the country has since been diverted by exile and business. For example, former student leader Wang Dan still calls for democracy but cannot set foot in mainland China and former Peking University students union president Xiao Jianhua became a billionaire before being detained in a corruption investigation.

Since 1989, many intellectuals have also come under intense political pressure to toe the party line and become advocates of nationalism, shoring up the party’s authoritarian rule. Kong Qingdong, who briefly joined the student movement as a leader, gained notoriety in recent years for his provocative nationalist comments.

“These three people are very typical and [their paths] epitomise what happened to intellectuals,” Yu said.

Xi Jinping tells Chinese police they must maintain social stability ahead of politically sensitive Tiananmen anniversary

But allowing too much nationalism can backfire, observers say.

Zheng said one example was the criticism the authorities were facing at home over talks to end the trade war with the United States, with nationalistic internet users in China accusing Beijing of compromising too much with Washington.

“There is enormous pressure with the trade talks. The Chinese public thinks China is surrendering to the US. The trade delegation is facing a lot of pressure and there is a lot of criticism online,” Zheng said.

Apart from raising internal risks, the party’s decision to sweep the crackdown under the carpet has wider implications for its international reputation.

Zheng said international mistrust had dogged China in the 30 years since Tiananmen, and resonated today.

“June 4 is a turning point. Before June 4, the West still had high hopes that China might develop like the West. Even Chinese society thought so. They thought they could develop like the West through reforms,” Zheng said.

By refusing to vindicate June 4, China was stating its rejection of universal values.

“Ideology is what is really behind the trade war. The West has lost its hope on China because they think China has given up on universal values,” he said.

“The trade war is only an illusion – it is about conflicts of ideologies and material interests.

“The West is thinking you are not only not changing your political system, you are even becoming a threat to the West.”

Wikipedia blocked in China ahead of Tiananmen Square anniversary

In addition, the 30-year waiting game has fostered widespread distrust in Hong Kong and Taiwan of the party, undermining Beijing’s long-stated aim of bringing Taiwan back into its fold.

So much so that last year, former Beijing-friendly Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou repeated his position that discussion of unification would not be possible if the official assessment of June 4 was not reversed.

Wang Kung-yi, a political-science professor of Chinese Culture University in Taipei, said the Tiananmen crackdown gave a lasting bad impression of the way the party dealt with people.

“Such a bad impression has served only to discourage Taiwanese people who are used to democracy and freedom from embracing cross-strait unification,” Wang said.

But that did not have to be the case, according to Zhao Erjun, son of Zhao Ziyang. He said that before his father died, he thought that a flourishing economy and a more relaxed political system would pave the way for reunification with the mainland.

“Why don’t Hong Kong people believe China can keep its promise that Hong Kong won’t change for 50 years? Why are Taiwanese resistant [to unification]?” he said rhetorically.

Back in Beijing, time is slowly draining away for the Tiananmen Mothers, the families and friends of those killed in the crackdown. You Weijie took over as spokeswoman of the group in 2015 when the husband of 82-year-old founder Ding Zilin died.

Over the years, she has watched the elderly parents of those killed in the crackdown die one after another and the remembrances of the period fade. From the 180 initial members, the group has dwindled by at least 50.

“We feel so disappointed every time someone passes away,” she said.

To this day, You still cannot lay flowers at the place where her husband died and avoids setting foot in Tiananmen Square.

But she is determined to keep up the call for a detailed record of the number and identities of the people killed that night.

“We have persisted for 30 years, and we will continue to do so.”

Additional reporting by Keegan Elmer, Mai Jun, Minnie Chan and Lawrence Chung

The next instalment in this series will look at how June 4 transformed the political landscape in Hong Kong.