Inspired by rare protests on mainland, Chinese students in North America organise and speak out

- ‘So many of our compatriots can do such a courageous thing, why can’t we?’ says Ava, who attends the University of Toronto

- Events have taken place or are planned at more than 50 universities in the US and Canada – top destinations for Chinese students

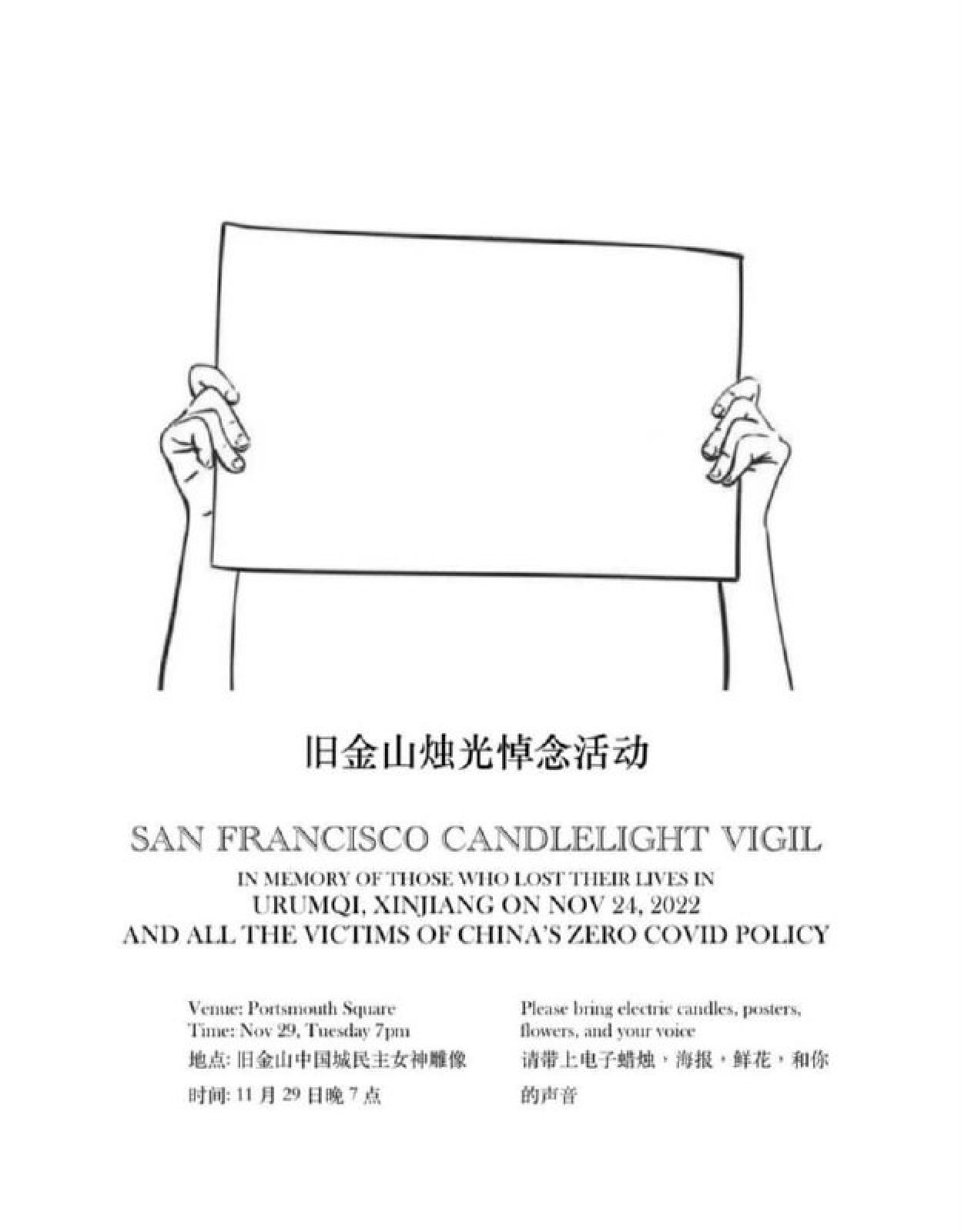

By Monday at 6.40pm a crowd of over 100 had gathered at George Washington University’s Kogan Plaza. They had come to honour victims of a deadly fire in Xinjiang the week before – deaths that many blame on China’s “zero-Covid” lockdowns.

The plaza was adorned with candles, flowers and protest signs, but there was no event programme and no clear leader.

Many people there had found out about the protest just hours before. The event was thrown together the previous day by mainland Chinese students with little to no organising experience – driven by a desire to respond to developments back home despite the personal risk that came with visible dissent.

Students and others from various diasporas – mainland Chinese, Uygur, Hong Kong, Taiwanese and Ukrainian – took the stage to speak. Chants calling for easing Covid restrictions and bringing down the Chinese Communist Party punctuated the sometimes awkward silence in between.

Outside the mainland, overseas Chinese in at least 23 countries have planned vigils at campuses, civic spaces and Chinese consulates. By Wednesday night, events had taken place or been planned at 52 universities in the US and Canada – top destinations for Chinese students.

The impromptu nature of the George Washington protest was not unique. At the University of California Berkeley, a similar vigil was held on Monday, with participants bringing different components – flowers, candles, sound systems – with little to no prior coordination.

Mike, a mainland Chinese student at Berkeley’s law school, said that although he created and disseminated event posters, he didn’t know the people who brought the other materials.

He said there was such a strong desire to respond to the Urumqi fire that had he not put up posters on Sunday, someone else would have. “The momentary anger has overcome any long-term fear of repercussions,” he said.

‘A new situation’: is China on the verge of changing its zero-Covid strategy?

In Canada, Ava, a mainland Chinese student at the University of Toronto, said her and her classmates’ experience with the “Bridge Man” protest in October inspired a stronger, more coordinated response this time.

On October 13, days before the 20th Communist Party congress that granted President Xi Jinping a third term, a lone protester took to Beijing’s Sitong Bridge and unfurled two banners calling for a nationwide strike, deposing Xi and ending harsh Covid restrictions.

Though the man was quickly arrested, mainlanders fought Beijing’s tight censorship to share supportive messages online, on bathroom walls and via iPhone’s AirDrop function. The same month, posters and protests supporting the Bridge Man sprang up across at least 350 campuses in over 30 countries, according to Citizens Daily, an Instagram account that tracks the overseas response to China-based protests.

Ava, who helped arrange a protest in addition to putting up posters in October, said the current response was “larger and more energetic”. Only a dozen people attended her October event, but on Sunday, hundreds appeared at the rally she helped organise in front of Toronto’s Chinese consulate.

“Many people got connections and experience from our Sitong Bridge protest, which for many of us was our first time organising,” she said, noting that this time, she coordinated with the Assembly of Citizens, a Toronto-based student group founded in 2020 with mainland Chinese members across dozens of Canadian universities.

Unlike in October, “protests have erupted in multiple Chinese cities and universities”, she said. “So it is more inspiring to overseas Chinese who see that and say, so many of our compatriots can do such a courageous thing, why can’t we?”

The bridge protest was a turning point, they said, because it occurred right before Xi’s third term was cemented – a move that, for many, was the “final straw”, said Mike.

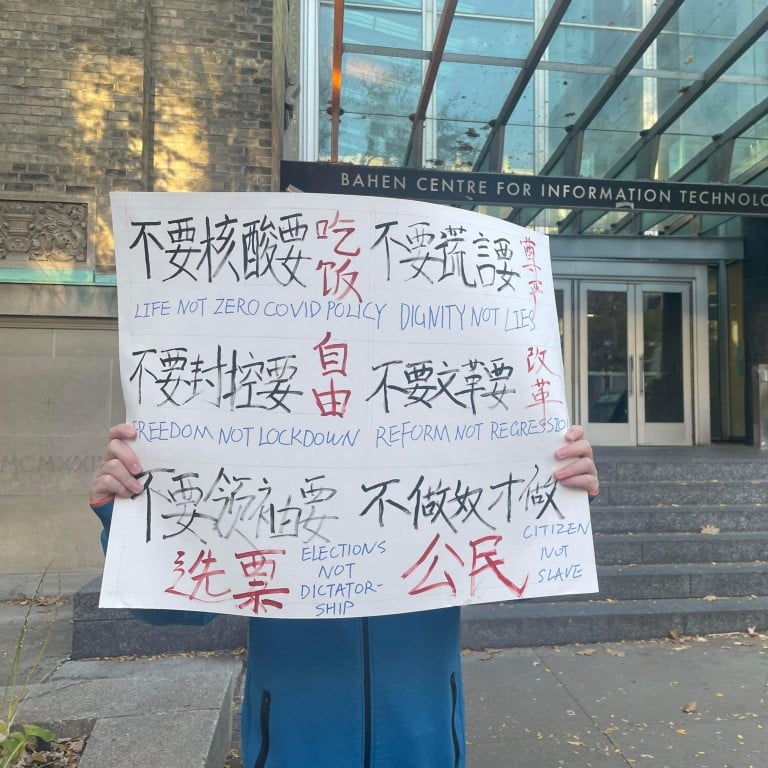

Slogans and blank paper banners as patience over China’s zero-Covid wears thin

Johnson, a mainland Chinese senior at George Washington who distributed posters for Monday’s protest and also in October, said the Bridge Man’s demands resonated broadly because they were so tangible. “If we just talk about democracy, a lot of Chinese people won’t feel that it’s important,” he said.

“Their spirit made me more daring to take the risk,” he said.

Ava decided to protest to encourage fellow Chinese students to do the same. “If they can see an example from someone like them, they might feel less scared or intimidated to speak out,” she said.

Although Ava, Mike and Johnson knew of growing dissent among overseas students, they were still surprised by protest numbers.

Demonstrations are common at North American universities, but they rarely feature Chinese students at the helm.

Ava describes most Chinese students she first met in Canada as politically apathetic. Now, though main protest organisers come from social science or humanities backgrounds, STEM students and others who are normally apolitical are also participating.

Rebecca Karl, a New York University professor who studies Chinese dissent, noted that for the first time in 28 years, mainland Chinese students have reached out for guidance on protest strategy.

Anti-Covid lockdown protests flare across China after deadly Urumqi fire

Said one Chinese speaker at Kogan Plaza on Monday: “Over the past 10 years, I’ve often felt incredibly lonely in my sense of shame for my government … I felt that I was someone who wanted my country to be better in a way that other people didn’t seem to care about.”

Another participant said he used to be a “little pink” – a term used to describe jingoistic digital warriors in China – but that recent events had opened his eyes.

Despite the unity in sentiment displayed on stage, however, opinion varies on whether to focus demands on Covid restrictions or on broader political change as well.

“There is reservation in terms of how much to expand the message beyond Covid policies,” said Mike. “Some say we don’t want blood on our hands by encouraging tougher crackdowns on people back home.”

Some at the George Washington University vigil stayed silent when the crowd chanted for an independent East Turkestan – the name Uygur activists use for Xinjiang. At Berkeley’s vigil on Monday, the Chinese national anthem played over speakers.

But outright opposition to the protest activity has been rare. Wester, a student leader with the Assembly of Citizens, said some counter-messaging appeared in a group chat, but was limited.

Ava said she saw posters torn down in October, but nothing like in 2019 when counter-protests were held as Hong Kong students demonstrated against the extradition law.

Broad support appeared to be the greatest theme of students’ initial efforts, including from older generations of mainland students and other diasporas that have more experience in organising against the Chinese government.

Alex Chan, a Hongkonger and an undergraduate organiser at NYU, said she was glad to help support mainland students in their protests. “There is so much potential energy here … there is no better time to get ahold of these overseas Chinese students and make sure that we’re all connected,” she said.

Which Chinese Covid controls are fuelling public anger?

Mike from Berkeley is sceptical about the longevity of the efforts, but said the contacts he’s made may have long-term effects, especially as limited opportunities to stay in the US after graduation force Chinese students to return home. The connections made through the protests form the “basic infrastructure” for further activity, he said.

Johnson said recent events signal an “important positive shift” and give him a “glimpse of hope”, although he’s still pessimistic overall because “a lot of Chinese people are still nationalistic”.

In this case, “they may be empathetic to Uygurs,” in whose neighbourhood the fatal fire broke out, but they “might not tolerate any secession or even greater autonomy of places like Xinjiang.”

The students’ “small actions” are not insignificant, said Xu Bin, a sociology professor at Emory University. “They enhance the awareness of social and political issues in a quiet, gradual way and demonstrate an alternative choice of action and an imagination of an alternative future” he said.

Ultimately, the marker for success may not be how effective the protests are in achieving change in China.

“A lot of people have sent me private messages saying they’re very touched and grateful to see other people putting up posters and protesting,” said the administrator for Northern Square, another Instagram account tracking and coordinating overseas response to the protests. “Even though they do not know each other, they kind of feel the energy. So I think that’s the meaning of all of this.”

Additional reporting by Orange Wang and Kinling Lo