Exclusive | Former top US trade negotiator Charlene Barshefsky says China deviated from its commitments, paving way for trade war

- Inaction by previous US administrations also helped lay the groundwork for the current impasse, Barshefsky says

- Beijing’s state-run economic model ‘means that volatility will be a hallmark of China's relationship with the US and with other countries’

This year marks four decades of normalisation of ties between China and the United States but the anniversary has been overshadowed by an unprecedented trade war and tensions over security and ideology. To commemorate the event, the South China Morning Post is publishing a series of stories throughout the year taking a deeper look at how the relationship between the two nations has evolved. Here, former US trade representative Charlene Barshefsky shares her views on China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation and the US policy of engagement with China.

China’s backsliding on market reform and its trade practices in the past decade is “very disturbing”, said Charlene Barshefsky, the former US trade representative who opened the door to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) for China.

In a wide-ranging interview about China’s economic growth and relations with Washington, Barshefsky blamed Beijing’s deviation from market principles and inaction by previous US administrations for helping to lead to the current impasse.

“China has adopted an alternative path that simply seeks to treat its market in the way in which it wants regardless of the rules or commitments made and therefore impinges on the rights of China's trading partners regardless of the rights that they have,” Barshefsky said, speaking of China’s economic path since the mid-2000s.

“This is a very disturbing outcome not in China's interests, as we see China's economy was slowing before all of this trade stuff happened.”

On January 1, China and the United States witnessed the 40th anniversary of their diplomatic ties, which have grown to become the world’s most important bilateral relations.

Barshefsky, the top American trade negotiator in the Clinton administration from 1997 to 2001, was the US mastermind of a bilateral pact signed in November 1999 that gave American companies greater access to Chinese markets.

What is China’s latest economic move to offset US trade war?

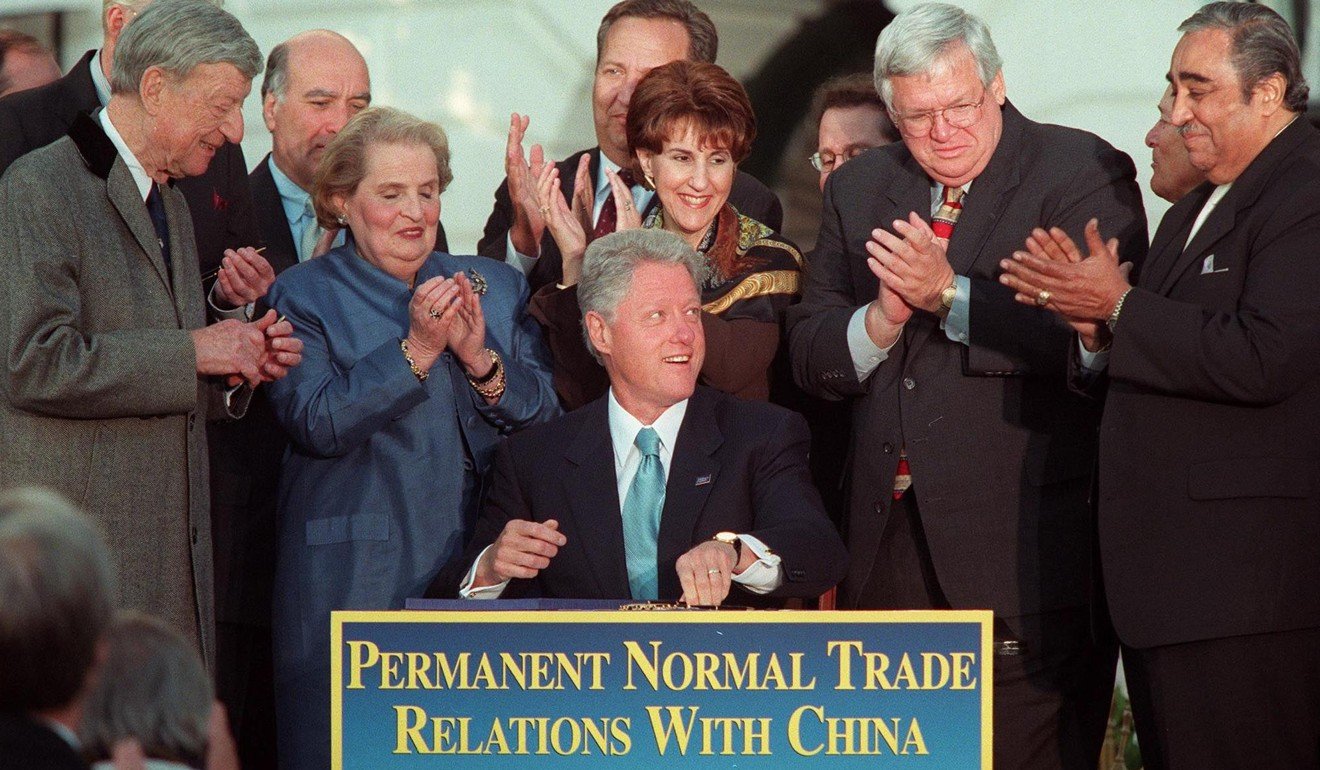

It was one of the biggest trade deals in history, helping Congress pass a law in 2000 that permanently normalised trade relations with China and paving the way for China’s accession into the WTO the following year.

Then-president Bill Clinton called the admission into the WTO “the most significant opportunity to create positive change in China since the 1970s”, when the Communist nation that had been behind the bamboo curtain first opened its arms to Washington, after a rivalry of more than 20 years.

By lowering the barriers that protected China’s state-owned industries, Clinton argued in a 2000 speech, the US could expect Beijing to speed up its departure from the state-led economic system, which he said was a major source of the Communist Party’s power.

In retrospect, said Barshefsky, who led the US side in the negotiations, those hopes had dimmed as early as 2006, as China turned its back on robust market changes and adopted a model that she described as “significantly state-run” and that discriminated against foreign companies.

“It means that volatility will be a hallmark of China’s relationship with the US and with other countries,” said Barshefsky, now a senior international partner with the WilmerHale, a Washington-based law firm. “That’s not good for anyone, and it’s certainly not good for China.”

After years of build-up, trade tensions between the US and China overflowed in July into a tit-for-tat trade war. US President Donald Trump had threatened to put punitive tariffs on virtually all Chinese imports, but the two sides agreed on a 90-day truce and further negotiations during a meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping on December 1 in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

While Barshefsky, a firm supporter of multilateral settlements of trade disputes, shrugged off most of Trump's theories behind the trade war, she admitted that previous US administrations were partly to blame for the “explosions” in US-China relations.

“The failing has been really twofold: one that … in 2007 or so subsequently China’s economy and economic policy began to diverge from market economics,” she said.

“The second failing was on the part of the US and China’s trading partners for not more carefully enforcing the WTO agreement, including very special and unique provisions in their agreement that pertained only to China.”

Those provisions could be used to curtail some of China’s most controversial practices, including forced technology transfers and market disruption, but have rarely been used, she said.

“I think had enforcement been more robust, we would not see the explosion that we see today particularly in US-China relations.”

A provision in the agreement allowing China into the WTO stipulated that it should not condition the distribution of import licences on the transfer of technology, which would suit the description by most companies as China s forced transfer of technology. But Barshefksy said the US had never applied the provision.

Though she said Washington’s punitive tariffs on China were “disturbing” and not consistent with WTO norms, she agreed with the Trump administration that trade outcomes with China were “lopsided”.

“One can look at conditions on the ground in China for foreign companies, and those conditions are far less welcoming than they were in years past,” she said. “So I think those observations by the administration are correct.”

An “astounding” 75 per cent of companies felt they were less welcome in China than before, according to the annual “China Business Climate Survey Report” by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, issued in July.

Most companies said China’s “IP leakage” and data security issues were worse than other countries, and a quarter of those surveyed said their top intellectual property challenges were the lack of legal IP protection and the difficulty of prosecuting infringements.

The chamber also called for Washington to “advocate more strongly” for a level playing field for US businesses in China.

The grim picture looks far different than Barshefsky's vision two decades ago, when she led US efforts in the late 1990s to bring China into the WTO.

I think had (WTO) enforcement been more robust, we would not see the explosion that we see today particularly in US-China relations.

During a US House Ways and Means Committee hearing in 2000, a year after Washington and Beijing reached agreements on WTO entry, Barshefsky said China’s membership had “potential beyond economics and trade”.

She argued that the entry could serve to advance the rule of law in China, and establish a precedent for willingness to accept international standards of behaviour in other fields.

The belief that WTO entry could be a foundation for broader reforms was shared by a number of leading advocates of democracy in China, she said in her 2000 testimony, including Bao Tong, the most senior Chinese official jailed for sympathising with pro-democracy student demonstrations in 1989, and Martin Lee, then leader of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party.

Looking back at the hopes of 18 years ago, Barshefsky said she now saw a “mixed picture”, though some improvements have been seen in the China’s transparency and quality of its court system.

She said China’s legal process “has become complicated” as the Communist Party had put itself above the law, “whereas other countries place the law above party and above the individual”.

“I think it's probably a mixed picture but better than it would have been without,” she said.

On December 18, China celebrated the 40th anniversary of its reform and opening-up policy, which extracted the country from the wreckage of the Mao era and led to a four-decade economic take-off.

In a widely viewed speech last month, which observers believed could signal further market reforms to address grievances from the West, Xi reiterated the leading role of the Communist Party in driving China’s growth, to the disappointment of many China observers in the US.

Yet Barshefsky said there was still plenty of room for China to manoeuvre for its market reforms.

“I don’t think anyone asked China to change its political system,” she said. “It doesn't mean it has to be a Communist Party that controls prices or output or factor inputs or companies or technology or any of the rest of it.”

“China was headed toward greater market economics and a greater market economic-based system from 1978 to 2007. The party existed.”

As China and the US engage in a 90-day truce looking to settle the trade war that has rattled global markets for months, Barshefsky said it was crucial for China to return to the path it was on before 2007, which she described as one featuring significant reforms.

“The reforms and the opening of China’s market, which were so robust in the earlier years of its WTO accession, started to sputter around 2006, 2007 and have virtually ceased except in a very limited sense,” she said.

“So returning to this reform and opening path becomes, I think, very critical. It has proven results for China.”

Mark Wu, a law professor at Harvard University who worked in the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) during the George W Bush administration, echoed her analysis.

“Undoubtedly, China’s desire to join the WTO played a major role in spurring market-oriented reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s and prevented them from being undone by conservatives,” said Wu, who was the USTR’s director for intellectual property from 2003-04.

“Since 2006, China’s economy has continued to engage in periodic reforms, but not necessarily in the direction expected originally by the West in the early 2000s.”

While opportunities for private businesses and foreign firms continue to expand, the state has kept tight control over strategic sectors that it considers crucial to the economy, he said.

Despite widespread pessimism regarding a permanent resolution to the trade dispute, Barshefsky, who was famously known for packing her suitcase twice during the final round of WTO talks, remains positive that China can find a way out.

“I do think that China, of course, is more powerful than it was during the WTO negotiations,” she said. “But the fundamentals remain, which is that the Chinese are extremely creative and adept at finding solutions to problems when those problems arise.

“I think that they certainly were in 1999. I think they remain so today. And so I have great hope that China will find its way in the current dispute.”