Chung Kuo, revisited: how Antonioni’s 1972 documentary on communist China was unfairly attacked – and finally vindicated

- The Italian director was invited by the Chinese government in 1972 to make a film singing the praises of the communist revolution

- His film was banned in China for 40 years and is the subject of a new Chinese documentary, Seeking Chung Kuo, that talked to people from the original film

In 1972, Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni toured China at the invitation of then premier Zhou Enlai and made a documentary about the lives of ordinary Chinese during the Cultural Revolution. The film – Chung Kuo, Cina – sparked one of the biggest, and least warranted scandals in cinematic history, something which plunged its director into despair.

Conceived by Italian public broadcaster RAI and the Chinese embassy in Rome, the idea behind the film was to have a leftist filmmaker visit China and make a film singing the praises of the communist revolution.

However, Antonioni shot a film that was worlds away from propaganda – a 217 minute travelogue showing ordinary Chinese in tattered clothing amid nondescript architecture.

Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, who used the film as a pretext to attack Zhou – bad luck for a director who was at the peak of his fame and creative powers. Chung Kuo, Cina, together with the rest of the director’s works, were soon banned in China.

How Bruce Lee’s Warrior TV series was brought to life

Subjected to relentless attacks in the state media, Antonioni was branded an enemy of the Chinese people. Under pressure from Beijing, several foreign screenings of the film were cancelled, and Italy’s communists picketed his appearance at the Venice film festival.

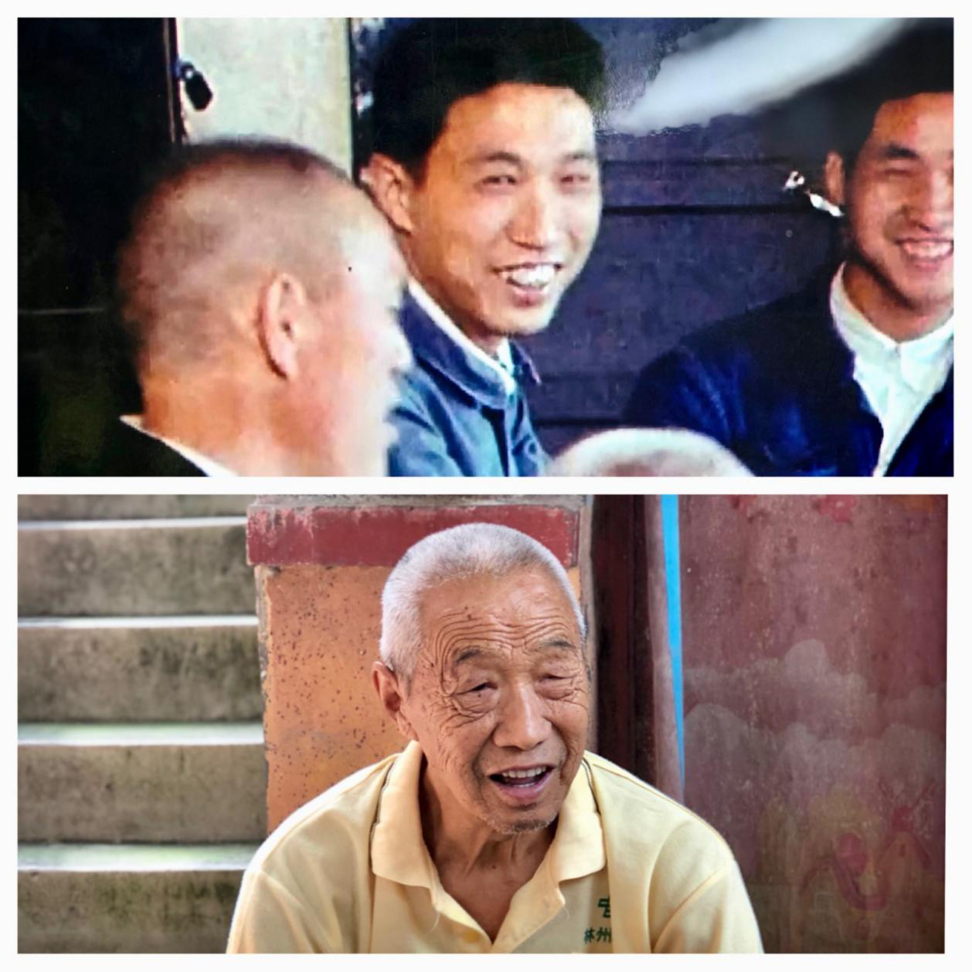

This ignominious chapter in Antonioni’s career is the subject of a new documentary, directed by Chinese filmmakers Liu Weifu and Zhu Yun. Titled Seeking Chung Kuo, it revisits the cities seen in Chung Kuo, Cina, to dig out some of the people Antonioni captured on camera four decades ago. The filmmakers hope to explore how China has changed since then by revisiting the Italian’s film.

“He objectively captured many villages and faces of ordinary people. I was not born when the film was made. It is very precious footage for me,” Zhu tells the Post. “The people who were captured on camera were randomly selected. They didn’t know what [Antonioni was doing]. We decided to go to the same places and locate those people to see how their lives have changed.”

The film, which will be shown by Chinese state broadcaster CCTV, is narrated in Mandarin by Chinese-speaking Italian journalist Gabriele Battaglia, who traced Antonioni’s journey to Beijing, Anyang, Nanjing, Suzhou and Shenzhen. With the exception of Shanghai, they visited all the Chinese cities where Antonioni filmed Chung Kuo, Cina.

“There was no direct flight between Italy and China then,” says Liu. “Antonioni and his crew flew from Rome to Paris and on to Hong Kong. They then took the train from Hong Kong to cross the border to Guangzhou to fly to Beijing. When they arrived at the Shenzhen border, there was nothing but small villages there.”

While Chinese censors in the 1970s attacked Antonioni for making a banal film that failed to show the benefits of the communist revolution, the ordinary Chinese he came into contact with have fond memories of the dashing Italian and his beautiful then-girlfriend, Enrica Fico, who served as his assistant on Chung Kuo, Cina and who later married Antonioni.

Followed everywhere by government minders, the film crew drew crowds of curious onlookers who had never seen foreigners before.

Among the people caught on camera by Antonioni were a noodle shop manager in Suzhou; children and teachers from a kindergarten in Nanjing; a village chief in Anyang, Henan province; and a woman undergoing acupuncture anaesthesia for a caesarean section in a Beijing hospital.

Liu says when the documentary makers approached the subjects Antonioni filmed, they were surprised to find these people still have vivid memories of the filmmaking experience.

The noodle shop manager recalls how Suzhou foreign affairs officials came to her to demand that she write a criticism of Antonioni. “He just captured the real side of China then. There was no need to criticise him like that,” she tells Battaglia in Seeking Chung Kuo.

What North Korean films are like: propaganda, potatoes and Japanese ninjas

Liu says that although Antonioni was a left-leaning director, his works did not have obvious political messages. “How he captured the images in Chung Kuo, Cina is only an expression of his personal [artistic] style,” he says.

He and his crew also tracked down the filmmaker’s widow, Enrica Antonioni, and the other Italian members of Antonioni’s film crew, and filmed at Antonioni’s grave.

Enrica Antonioni says in Seeking Chung Kuo that he was completely destroyed by the negative reception the Chinese gave his film. “It was like the film failed. It was not well accepted. He put so much work into it. The editing alone took six months. It was so much love to make the film. When the country said, ‘you are our enemy’, it was like killing him,” she says.

It wasn’t until 2004 that Chung Kuo, Cina was finally shown publicly in China, in a screening for 800 people at the Beijing Film Academy. That was too late, Enrica Antonioni says in Seeking Chung Kuo. “When they told him the film was accepted [finally in China], he already couldn’t speak [due to old age]. Otherwise, he would have come to China, as he loved to watch his films with the public, especially the young people. For sure he would have gone to the university to see the film with the young generation.”

Liu adds, however, that Antonioni’s widow was happy to see the breathtaking development of China over the past four decades. “She told us she wants to visit China again, as her feelings on China now are completely different than before,” he says.