Planned Hong Kong mediation centre to bolster China’s influence in Africa

- Beijing reached agreement with unspecified number of countries last month

- Office to be set up next year to prepare ground for inter-governmental mediation court

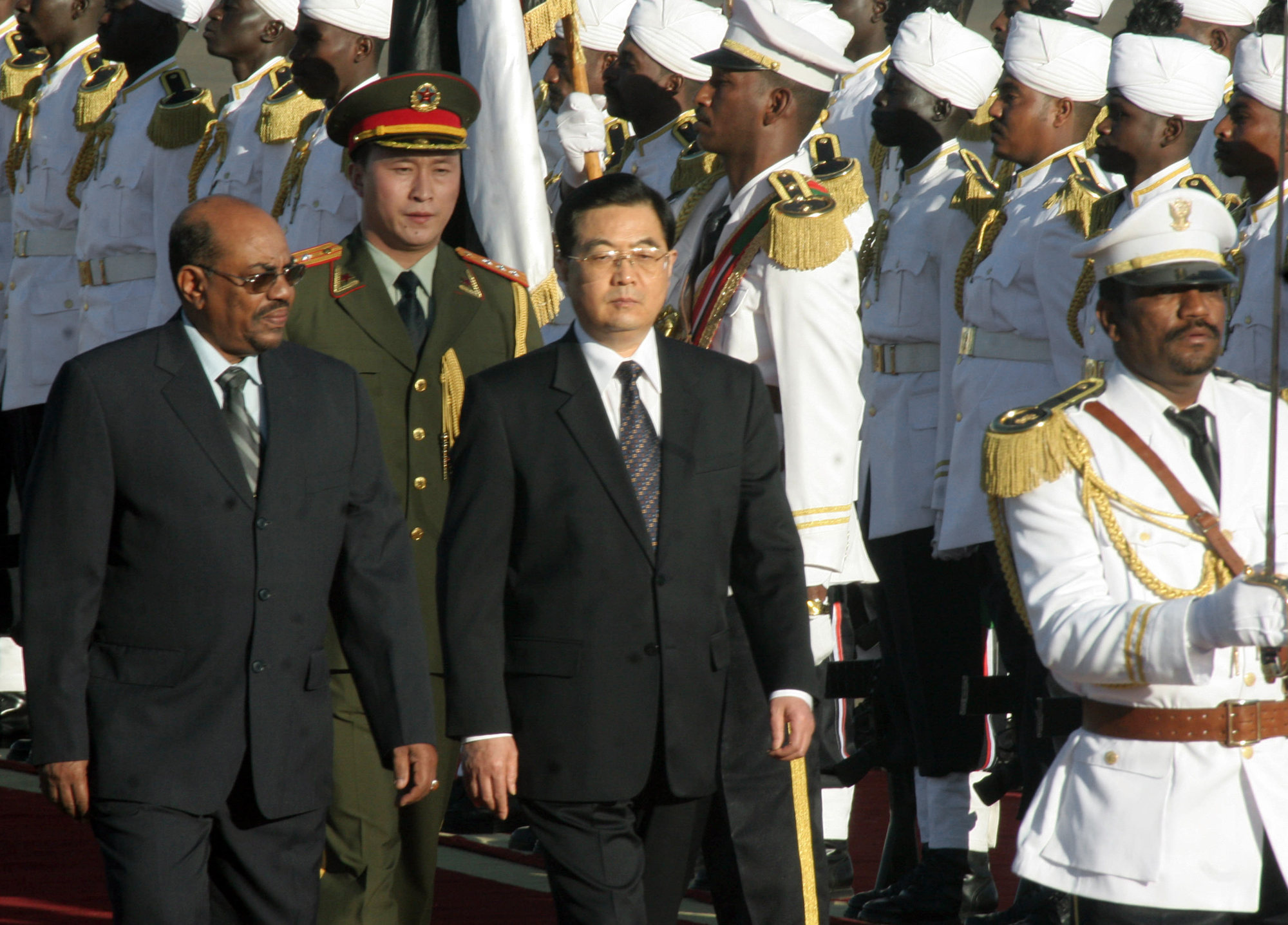

In the Chinese mediation playbook, the Darfur war in western Sudan was Beijing’s first attempt to resolve a major conflict.

Beijing abstained from some UN Security Council resolutions on Darfur and appointed a special envoy to push Khartoum to end the war that erupted in 2003, killing thousands and displacing millions.

Sudan will hand over Omar al-Bashir to be tried over Darfur killings

China recently announced that it wants to play a bigger role in promoting peace and security in conflict-scarred countries such as Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia.

It plans to establish an international mediation centre in Hong Kong as part of its broader goals of influencing and shaping international legal regimes and protecting its economic and commercial interests.

A preparatory office will be set up next year to lay the groundwork for the establishment of an inter-governmental mediation court, the Hong Kong government said on November 1, referring to it as an international organisation for mediation.

Beijing reached an agreement with an unspecified number of countries last month to set up the centre in Hong Kong.

Sudan, a prospective member of the organisation, said “the idea was initiated by China to unify the visions of countries around a common charter”.

“It will work to resolve internal conflicts of the organisation’s countries, in addition to resolving disputes with each other,” Sudan’s acting foreign minister, Ali Al-Sadiq, said on October 27.

The setting up of a mediation centre to handle inter-governmental or political and commercial disputes is part of China’s game plan to become a stronger and more active player in international mediation.

President Xi Jinping made that clear in the report he delivered to last month’s Communist Party national congress, saying “China is committed to building a world of lasting peace through dialogue and consultation”.

Continuity and caution key to China-Africa ties in Xi’s third term

Seifudein Adem, an Ethiopian global affairs professor at Doshisha University in Japan, said it was only natural that Beijing was creating an international institution designed to mediate conflicts within or between “friends” of China because it distrusted international institutions created by and for the West that did not reflect its values and preferences.

“Even though it may be of limited scope, for now, the creation of a mediation centre can therefore be interpreted as a reflection of China’s increasing dissatisfaction with some of the norms governing this substructure of the interstate system,” Adem said.

For several years, Chinese authorities had been thinking about international dispute resolution and building institutions to address cross-border disputes, particularly commercial ones, said Matthew Erie, an associate professor in the faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern studies at Oxford University.

Erie, who is the lead researcher on a project studying China’s approach to global law and development, said a number of such institutions had been established, both in and outside China.

China’s Horn of Africa envoy offers to mediate regional disputes

“But supplying such services and parties using them are two different things, and it remains to be seen whether these fledging dispute resolution mechanisms can take root,” he said.

Moritz Rudolf, a research scholar in law and a fellow at the Paul Tsai China Centre at Yale Law School, said China wanted to be seen as a “responsible global stakeholder in the realm of international relations and international law”, and Xi had made the application of legal means in international matters a priority.

Beijing had focused on mediation as a mechanism for domestic conflict resolution for decades, Rudolf said, and at the international level it had been promoting mediation to resolve international commercial disputes.

He said that under the Belt and Road Initiative umbrella, China had been advocating an international one-stop dispute-resolution mechanism that included commercial litigation, arbitration and mediation.

By building a non-Western parallel structure to solve conflicts between states, Rudolf said China aimed “to increase its international prestige but also to engage in low-cost stabilisation efforts to protect its economic interests abroad”.

But Liselotte Odgaard, a professor at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies and a senior fellow at Hudson Institute, said China had tried to play a mediating role in Africa for a while, with limited success.

“As China’s competition with the West takes off and China focuses increasingly on the so-called Global South, China wants to present itself as a more serious and competent mediator in conflicts,” she said.

Odgaard said the planned opening of the mediation centre showed that “China wants to obtain legitimacy for this seemingly benevolent role and demonstrate that it can replace the West as a mediator in conflicts”.

China’s investment in Africa will return as pandemic effects ease

Paul Nantulya, a research associate at the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies at the National Defence University in Washington, said China’s efforts to establish alternative international mediation and arbitration institutions were driven primarily by economic and commercial interests.

He said that with more than 40,000 Chinese state-owned enterprises operating globally, all manner of disputes could crop up on any given day, potentially involving billions of dollars.

“The Chinese government – which supervises these SOEs – is anxious to have as many of these disputes as possible resolved in its favour,” Nantulya said. “The establishment of a government-led international mediation centre in Hong Kong should be viewed within this larger context.”

He said Hong Kong was already a leader in international dispute resolution in its own right, handling over HK$54 billion (US$6.9 billion) worth of cases last year.

Adem said that since Hu’s visit to Sudan in 2007, China’s desire to play a part in resolving African conflicts seemed to have increased along with its expanding power, interest and influence in Africa.

But he said that China would, in theory, be a more suitable mediator of interstate disputes such as the one over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, than intrastate conflicts involving sub-state, non-state or transnational actors.

Adem said that was partly due to the principle of “national sovereignty”, which was the basis of contemporary international relations and something that China was extremely sensitive about in terms of its own place in the world.

“What must also be remembered is that Africa has had fewer conflicts among states than within them,” he said. “China’s mediating influence on African conflicts is thus likely to be negligible.”

Chinese foreign minister set for 3-nation tour of East Africa

During a trip to Africa in January, Foreign Minister Wang Yi proposed steps to facilitate a Chinese-led peace process in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. Since then, China’s special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Xue Bing, has made a series of whirlwind visits to the region.

Benjamin Barton, an associate professor at the University of Nottingham’s campus in Malaysia, said the initiative in Hong Kong aimed to challenge the dominance of arbitral chambers that were located predominantly in the West as well as the preponderance of Western legal practices when it came to solving disputes.

He said that if Beijing was able to promote a Sino-centric alternative, it would not only benefit China’s national interests, but also assist its efforts to buttress “the value of its alternative authoritarian value system”.

Beijing’s ambitions would, however, be limited by foreign investors’ concerns about its opaque judicial system when it came to selecting China as the jurisdiction for dealing with belt and road commercial disputes.